“The government’s share of the economy will continue to rise. The more government is involved in the economy, the less productive and efficient the economy becomes.” Long-time Barron’s Roundtable member, Felix Zulauf.

“I can almost hear Milton Friedman shouting ‘look out, here it comes’! Can it work out differently? Of course. Is that the way to bet? No, it’s not.” Bond manager extraordinaire Dan Fuss, referring to inflation.

“No, it’s strictly a temporary measure.” Former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, when asked in April 2009, if the Fed intended to maintain its quantitative easing policies.

As promised, this week’s edition of the Evergreen Virtual Advisor is a follow-on to last week’s issue. In it, I made the case as persuasively as I could that one of the most urgent questions of our time is whether Western societies should encourage a far bigger role in government entities in nearly all aspects of life. Presently, it seems that the answer is a resounding yes, at least among slightly over half of all US voters and their elected representatives.

It’s not just in America where voting support is swinging more toward increased state control and planning. Greater government involvement in almost everything seems to be pretty much a global phenomenon. Consequently, I’m in my familiar contrarian position because I don’t feel that trend is beneficial at all; in fact, I believe it is a grave threat to economic prosperity and individual liberties. Moreover, it’s my contention that the belief that more government direction is desirable, even essential, has resounding investment implications.

Before delving into my closing point from last week—that the West is on the brink of one of the most monumental transformations in its history, for better or for worse—let me bring up three former thought-leaders who have faded to the margins of popular culture. Based on the direction Western societies are headed, I think that’s a profound mistake.

The main two individuals I’m referring to are Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. Hayek first burst onto the intellectual debate stage in 1944 with his iconic—or iconoclastic, depending on your political persuasions—book, “The Road to Serfdom”. If you’ve never read it, I’d suggest you do so; at a minimum, you should check out the Cliff Notes version, particularly if you’re shocked and alarmed by the direction America is heading.

The reason that Hayek’s book was so counter-cultural at the time was that it challenged the then ascendant view that governments needed to employ central planning and some form of collectivism. This was the case even in America as our nation reacted first to the Great Depression and then to the existential threats from Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Certainly, in a world war, governments need to take on a massive role.

By 1944, however, it was clear the Allied powers, led by American industrial and military might, as well as a newly minted Russian war machine, would prevail over the Axis countries. Hayek was concerned that statism would continue to dominate the West even as peace returned. In certain countries, such as the UK, his fears were justified (and, obviously, in the victorious Soviet Union, Stalin’s iron grip never eased until his death in 1953). The increasing embrace of Socialism in Great Britain would eventually lead to a near economic collapse in the 1970s and a humiliating bail-out by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

In “The Road to Serfdom”, Hayek went to great lengths to point out that statism was behind the rise of Nazi Germany, a trend that was in place even before Hitler came to power. Of course, Soviet Russia, even before WWII, was every bit as ruthlessly state-controlled with brutal consequences for any who dared oppose the supremacy of the system. One of his points, with which I totally concur, is that there is almost no practical difference between Fascism and Communism. In my case, I’ve long believed that political theory isn’t a continuum but rather a circle. If you go far enough to the left or to the right, the two link-up—and the end result is a police state.

Hayek was a native Austrian; thus, he had a ring-side seat to the horrors of the Nazi regime which subsumed his country in 1938. In “The Road to Serfdom” he wrote, “Few recognize that the rise of Fascism and Nazism was not a reaction against the socialist trends of the preceding period but a necessary outcome of those tendencies. Yet it is significant that many of the leaders of these movements…began as Socialists and ended as Fascists or Nazis.”

Rob Sutton, writing in The Critic on January 12th of this year, aptly summed up Hayek’s work: “The central thesis of ‘The Road to Serfdom’ is that descent into tyranny is the ultimate and inevitable trajectory of a society in which the sovereignty of the individual is subverted in the accumulation of economic power by the state. Central planning leads invariably to authoritarianism. Hayek is not timid in making these claims. Studying the seemingly disparate political systems which dominated Europe in the run-up to the Second World War (communism, fascism, socialism), Hayek concluded that they each had a common endpoint—the development of a totalitarian state. Despite their contrasting social and economic goals, each necessitated the central consolidation of power and the explicit planning of an economy to achieve those goals.”

Why is it that what we consider to be far-left and far-right policies consistently lead to totalitarian governments? In my view, it’s because they inevitably produce economic distress—even collapse—requiring those in power to resort to all the familiar forms of brutality and suppression humanity has come to know—and fear--so well. A current and heart-breaking example is Venezuela.

It is a country with oil reserves even greater than Saudi Arabia and yet its oil production has shrunk to insignificance. That immensely energy-endowed nation is now forced to import fuel. The essentials of life—food, medicine, even water--are a daily struggle to obtain. Millions have fled. It’s hard to imagine that in the 1970s it was one of the wealthiest countries in the world. (It’s fair to note there’s been some modest improvement lately—thanks to the limited allowance of some free market activities!)

When the socialism of Hugo Chavez was first introduced in Venezuela, many in the West celebrated it. Hollywood was particularly embracing of the proudly socialist Chavez regime. Yet, even before Chavez died of cancer in 2013, the Venezuelan economy was in trouble. Inflation was running at 20% at the start of 2013 heading to 60% by the end of that year. Under his hand-picked successor (elections became a farce under the “Bolivarian Revolution”), Nicolàs Maduro, hyperinflation has become the norm, hitting 350,000% in 2019.

Certainly, both Hayek and Milton Friedman would have predicted the Venezuelan disaster well in advance. In a 1980 speech, while inflation was still raging in America, Friedman uttered these words, which were prophetic in the case of Venezuela (though he was referring to the US at the time): “If we continue to rely more and more on the government and less and less on the individual, we are condemned to a future of tyranny and misery.” Fortunately, for America, we made a radical policy U-turn, which resulted in two decades of economic resurgence under both GOP and Democratic leadership. (To watch Friedman’s stirring speech on economic freedom and the key policies necessary to ensure that, please click here.)

Friedman then took the Federal Reserve to task for the deflation it allowed to occur in the early 1930s as well as the chronic inflation of the 1970s. He wryly noted that the Fed gladly takes credit for good times but then when there are difficulties it contends these are the result of outside forces. (Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?) He then ripped the Fed for allowing the collapse of the banking system in 1933. Yet, the Fed gave itself great credit in its annual report of that year for preventing worse damage. From 1929 through 1933, Mr. Friedman observed, the US money supply declined by 1/3, and 1/3 of banks failed. Why? Because the Fed allowed it to happen. In his view, it had the power to prevent the decline in the money supply and, if it had, the Great Depression would have been “a garden-variety recession”.

He went onto say: “There were those in the Fed pleading with the central bank to stop the collapse of money and the banking system. Thus, the Great Depression was the result of government failure. We’ve learned, the Fed has learned. It won’t fail in that way again, it will fail in a new way. Inflation is made in one place and one place only—Washington DC and, the Fed, along with the major accomplice, Congress.” He also believes US voters share the blame; people want more spending but light taxes thus the government imposes inflation as a hidden tax. The public believes, or is led to believe, government somehow or other can spend money at nobody’s expense. He then quoted the brilliant French economist of the 19th century, Frederic Bastiat: “Government is that fiction whereby everybody believes they can live at the expense of everybody else.” Mr. Friedman added this was a classic example of the free lunch myth.

Bastiat also had another profound commentary, one that is eminently applicable to the economic policies being implemented in America today (courtesy of my friend Fred Hickey, a former member of the Barron’s Roundtable): “When false money, under whatever form it may take, is put into circulation, depreciation will ensue, and manifest itself by the universal rise of everything... But this rise in prices is not instantaneous and equal for all things. Sharp men, brokers, men of business, will not suffer by it; for it is their trade to watch the fluctuation of prices, to observe the cause. And even to speculate upon it. But little tradesmen, (rural workers), and (ordinary) workmen, will bear the whole weight of it. The rich man is not any richer for it, but the poor man becomes poorer by it.”

Wow, does that ever ring true today during our 12-year experiment of the Fed creating money from nothing! As we all know, the rich have gotten far richer due to the dizzying rise in asset prices thanks to the Fed’s $7 trillion (and counting) money fabrication. The lower- and middle-classes feel left behind, as they should. Also related to one of his points above, those of us in the money management business, who recognize how things are trending, have been able to capitalize on this tsunami of false money being put into circulation for our clients and ourselves. . (A potential wealth tax might and the fact that capital gains aren’t indexed for inflation could be why the rich will eventually not be that much richer).

For many months now, these pages, at least those written by me, have advocated investing in hard assets, as well as those companies that benefit from reflation and the economy’s re-opening. It’s been a great place to be since last spring, and particularly post-the vaccine breakthrough news in early November, despite the correction in precious metals and the miners thereof. (This area offered a fabulous profit-making, and -taking, opportunity last year during their meteoric rise; personally, I think conditions are setting up for another surge, especially by the gold miners.) Thus far, however, widespread inflation in consumer prices has not yet occurred. If Hayek, Friedman, and Bastiat were still with us, though, I think they’d all say in unison: “Just wait”.

As Friedman and Hayek both point out, the people behind statist/socialistic/centrally-planned policies are generally not of ill-will--at least until the thugs' takeover during the nearly unavoidable economic collapse. Fortunately, many Western democracies have been able to execute a policy reversal (far better than executing dissidents!) before things got totally out of control. Those countries with less robust democratic institutions have, tragically, often devolved along the lines of Venezuela.

One reason Socialism and the belief that money can be painlessly created in vast quantities by central banks is highly popular is that it sounds so good. But then the inevitable specter of rapid, even hyper-, consumer price inflation appears. This causes extreme hardship for the poor and the elderly. Those closest to power are able to protect themselves in a variety of legal and illicit ways.

Consequently, no matter how attractive and noble your theories of economic and societal governance are, you may want to test them against reality from time-to-time (paraphrasing famed physicist Richard Feynman). The history of myriad countries shouts deafeningly that hard-core Socialism and the all-too-frequent reliance on binge-printing by the relevant central banks is truly the road to serfdom.

Hayek and Friedman both believed that there is a vital role for government in any society, a view with which I totally agree. For example, Hayek believed in a safety net for the poor and aggressive regulation against monopolies. He felt that a wise government needs to use its planning and regulatory powers for a competitive free market, not against it. He was very anti-cartels whether they be of private enterprise or the government itself.

As noted above, Friedman believed the Fed has a critical role to fill by preventing the kind of money supply implosion that happened in the early 1930s and also to prevent banking crises from going viral. Yet, I have little doubt they would both be horrified by the extent to which the US government is exerting ever greater influence over our lives and the far-too-immense power being accorded to the Fed. The latter is an institution that has failed the country multiple times from the Great Depression to the tech bubble, the housing bust, and now this unprecedented reliance on money printing and debt monetization.

This is not to say there were never good, even great, past Fed chairmen. There definitely were, particularly, William McChesney Martin and Paul Volcker. However, both followed policies much more closely aligned with Bastiat, Hayek, and Friedman and far removed from those of John Maynard Keynes (at least as they were distorted after his death in 1946) and, now, the guru of Modern Monetary Theory, Stephanie Kelton (former economic adviser to Bernie Sanders).

In EVAs long ago, I wrote of my NFL theory of good policy governance and I believe it still applies. The federal government should be like the officials in a football game: making sure it is played by the rules but NOT attempting to actually play positions. Imagine even the most athletic NFL ref trying to play for Russell Wilson or Tom Brady or trying to block Khalil Mack. It would be a fiasco. But it would also be a debacle if there were no referees and umpires. Cheating would become rampant, as would terrible injuries.

The same is true in business. If the private sector were allowed to operate without any regulations and oversight, the result would be jungle capitalism, a brutal and inequitable survival-of-the-fittest (or filthiest, as in most corrupt and ruthless).

However, when government becomes too meddlesome or actually tries to run businesses, the results are typically disappointing, if not disastrous. The UK relied heavily on nationalized industries after WWII. This played a major role in its economic near-death experience. Or in America, comparing the US Postal Service to Fed Ex or UPS is, well, actually, no comparison. (Have you noticed how long it takes for a letter to arrive via the USPS these days?) In Canada, the vaccine roll-out has been orchestrated by its monolithic healthcare bureaucracy with even less reliance on the private sector than in the US; the result is that less than 4% of Canadians have had one jab (vs 19% in the US).

This leads me to the massive transformation I alluded to in last week’s EVA and at the start of this note. The effort to decarbonize Western economies is a fantastically ambitious and complex undertaking. Moreover, the timetables being set are even more challenging. Many automakers are enthusiastically joining in the effort and are being embraced by ESG*-motivated investors. GM plans to be all-electric by 2035 and Volvo by 2030.

Unquestionably, electric vehicle (EVs) sales are going to grow rapidly, even exponentially. For one thing, they are much cheaper to maintain. But policymakers need to carefully consider the consequences of this unparalleled transition of the planet’s transportation system. As we’ve seen all too often, careful consideration is not what election cycle-focused politicians do best.

The first and foremost issue to analyze is the impact on the nation’s power grid from adding millions of additional EVs. Presently, EVs only make up about 2% of annual US car sales, or about 300,000 units. Another roughly 15 million cars and light trucks are sold each year with internal combustion engines. Consequently, attempting to power the majority of America’s vehicle fleet via electricity, even by 2035, is exceedingly aggressive, particularly with respect to the grid being able to handle this astronomical surge.

The viciously cold winter seen in much of the country last month underscored, once again, how fragile our electrical grid has become. The worst example of that was, ironically, in the politically conservative and energy-blessed state of Texas. In another irony, the leading producer of America’s crude oil is also one of the largest generators of electricity from wind.

Unfortunately, during its historic freeze, Texas’ wind power was reduced to just 12% of capacity. Natural gas didn’t fare a lot better, falling to 36% of potential output. Only nuclear was able to stay above 60% of capacity. Consequently, black-outs were widespread, including of oil and gas production facilities, magnifying the energy shortage. Nat gas prices in certain areas soared by hundreds of percent, sticking some Texas consumers with February power bills as high as $10,000 and causing the bankruptcy of one of the state’s largest electric cooperatives.

Reflecting rationally on the challenge of simultaneously electrifying the nation’s auto and truck fleet while making the grid ever more reliant on intermittent solar and wind power should raise serious concerns. (As renewable skeptics like to point out when the sun doesn’t shine or the wind doesn’t blow, the juice doesn’t flow.)

There is a school of thought that Western countries can have their energy cake and eat it, too. This newsletter has often pointed out the curse of The Economist magazine’s cover stories. Time and again, once an event—like the death of oil—makes it to its cover, the polar opposite is usually about to happen. Here’s one that ran last month:

*Environmental, social, and governance.

To my mind, this “no carbon, no blackouts” assertion is highly debatable. However, the counter to this is hoped-for breakthroughs in battery storage that can alleviate the intermittency risk. Those certainly can occur but in the here and now it might be wise to have a Plan B. Bill Gates, so often vilified by the political right (unfairly, in my view), has a new book out on the energy transition. From the reviews I’ve read, he is highly critical of excessive reliance on intermittent power sources and is a vocal advocate of nuclear power, particularly based on the latest technologies.

It’s also advisable to focus on the physics of energy. One barrel of oil contains as much energy as does $200,000, or 20,000 pounds collectively, of Tesla batteries. Accordingly, fossil fuels, for all of their emissions drawbacks, do hold a significant energy density advantage, as does nuclear power. Given this reality, it might be wise to include under Plan B making things like internal combustion engines (ICEs) produce fewer emissions. That might be radically less expensive—and less risky—than trusting that our dear policymakers can pull off both a mass conversion to EVs and the needed enhancements to the grid to power them. For example, Corning, the inventor of the catalytic converter, which is behind much of the 75% improvement in US air quality over the last 50 years mentioned in last week’s EVA, has a new filtration technology that further blocks ICE emissions.

It might also be a smart move to think about protecting as well as expanding the existing power grid. As many have rightly pointed out, our present system is extremely vulnerable to what’s known as an EMP, electromagnetic pulse, either solar- or human-caused, as well as geomagnetic storms. Should an EMP occur, it might totally fry the grid, shutting down the internet, possibly for months. If that were to happen, it would be Covid pandemonium squared, maybe cubed. Spending some of the enormous stimulus funds on protecting the grid would be far more logical than many of the intended uses. But it doesn’t generate the political dividends that sending thousands of dollars of aid even to well-heeled Americans does. Thus, grid protection will likely fail to occur—until disaster strikes.

In several past EVAs, I’ve written that one of the greatest vulnerabilities to the green power revolution is transmission lines. Recently, the very pro-renewable energy Financial Times (the UK’s “pink paper”; some wags say that color reflects its political leanings), ran an article titled “Activists take dim view of US power lines push”. In it, a Princeton University study was cited that America needs a transmission system 60% larger than today’s by the end of the decade, and possibly 3 times bigger by 2050, to achieve net-zero carbon output. Similarly, the new chief of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) stated—more like seriously understated—“We have to substantially build out the gird more than we have been doing.” Ya think?

The article further points out the fierce battles that have been going on for years about constructing transmission lines in the Northeast US to bring excess hydropower down from Quebec. The states of Massachusetts and New York, both of which have some of the highest consumer power costs in the US, have been seeking to access this clean power but the states of Maine and New Hampshire have other ideas. Joined by environmental groups such as the Sierra Club and the Appalachian Mountain Club, Maine and New Hampshire have been able to successfully block the transmission lines which were first proposed in 2010. (Germany is having similar transmission line warfare.)

So, it’s taken over a decade to attempt to build out an essential piece of a totally green energy project (Northern Pass), and it’s been stopped by an alliance of Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) and environmental groups. If anyone thinks this is an isolated case, they are kidding themselves. NIMBYism and conflicting environmental agendas are an unquestionable fact of life in hyper-litigious, factious America these days. (The fight over hydro-electric dams in Washington state is another example.) Accordingly, trillions can be printed up by the Fed and budgeted for clean energy projects by Congress but getting them to happen is a very, very different story.

Yet, I have no doubt this incredibly daunting energy transition will be attempted despite all the risks and with far too little consideration of the obstacles. As I’ve written before, it echoes the diesel engine push in Europe that started around 2000 and was supposed to be environmentally friendly (because diesel vehicles get better mileage). Instead, air pollution in numerous European cities greatly deteriorated, as automakers blatantly falsified emissions data.

Another “pink paper” article that I found fascinating was by Andy Palmer, former chief operating officer of Nissan. He was in charge of that company’s EV program that led to the Leaf, one of the best-selling EVs of all-time. In his words: “It will therefore come as no surprise that I am a vocal advocate for electric cars and the role they can play in helping to achieve a healthier planet.” Yet, his article was titled “Electric Vehicles may not be the climate solution after all.” (The Financial Times, 2/16/21.) In it, he also ridicules Europe’s “dieselgate” with the following: “The crux of the diesel saga was that politicians overstepped their mark. Instead of identifying the problem, writing the cheques, and leaving much of the rest to scientists and engineers—as they have done with vaccines—they fatefully dictated what they believed to be the solution.” There you have what I think is one of the best summaries of past energy policymaking failures…and those likely to lie up ahead.

Mr. Palmer goes on to say that there could be a multitude of other pollution-reducing technologies that are more feasible than an all-out push to EVs, such as hydrogen and cleaner-burning fuels. (He didn’t mention it but I would argue the Corning filtration system is another example.) To wit, “Politicians should avoid putting all their eggs into one glovebox.”

Unfortunately, most Western elected officials seem intent on doing exactly that. Because this effort has countless implications for the economy, investors need to be mindful of the investment consequences. Trillions of spending on green energy initiatives are likely to have much longer pay-back periods than anticipated and, I believe, inflationary implications due to high costs and inhibited productivity as a result of excessive focus on intermittent renewables. Consider that California and the Northeast states—with stringent restrictions even against natural gas—have power rates far higher than the rest of the country. And the political winds are blowing from those regions—literally, in some cases—across the rest of America.

Reflect, too, on what’s happening with oil prices currently. Energy companies are reluctant to invest in new projects, especially those expensive developments with long lead-times, because of the hostility of both the federal government and the ESG-focused investor base. Consequently, even after the recent spike by oil prices, energy producers remain very reluctant to sanction new projects. This is one reason I believe we will soon see $100, or higher, crude. Many environmentalists will probably cheer this as it deters oil usage but I doubt most consumers, who also happen to be voters, will see it that way. And, like so many trends currently, triple-digit oil, should it occur, will further stoke inflationary fires.

Perhaps you’re like me and you are stunned by the degree of the deterioration that has occurred in the US since our nation’s golden years under Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton. During the latter’s administration, just over 20 years ago, America was running consistent budget surpluses…and booming despite the supposed “negative stimulus” of inverse deficit-spending. The fact that we are now relying on economic policies that have been tried—and failed—in bankrupt developing countries continues to astound and terrify me. Perhaps I’m wrong, but I don’t see how real inflation, not just of the asset variety, doesn’t eventually return.

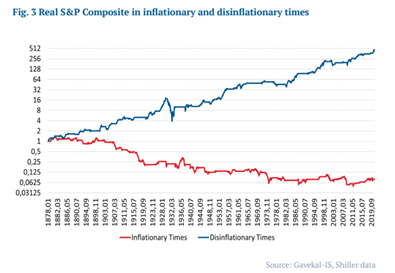

If you think this doesn’t matter to your stock portfolio, consider the following chart by Didier Darcet from our partner firm, Gavekal. As you can see it goes back, 150 years and reveals that virtually all the real gains over that time have occurred during disinflationary times. Inflationary eras have led to negative returns, after inflation.

A final point to wrap up this two-part series is whether one believes more in the ideology of Hayek and Friedman or that of Jay Powell and Janet Yellen, not to mention Congress. If you are optimistic that our current financial and political leaders have got it right with their policies, the antithesis of what Hayek and Friedman advocated, then your portfolio will look much different than that of someone, like me, who is taking the other side of that bet. Which position you choose might be one of the most important financial decisions you’ve ever made.

A final point to wrap up this two-part series is whether one believes more in the ideology of Hayek and Friedman or that of Jay Powell and Janet Yellen, not to mention Congress. If you are optimistic that our current financial and political leaders have got it right with their policies, the antithesis of what Hayek and Friedman advocated, then your portfolio will look much different than that of someone, like me, who is taking the other side of that bet. Which position you choose might be one of the most important financial decisions you’ve ever made.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.