In past reports, we have often argued that the most traumatic events are not always the events that end up casting the longest shadows. For example, anyone aged over 30 remembers where they were on 9/11. Suddenly, it felt as if the world had changed. Yet, economically speaking and in terms of long-term market impact, the most important event of 2001 was not the terrorist outrage, nor was it the unfolding tech bust, or even the Enron fraud. Instead, what changed the world in 2001 came exactly three months after the attacks on New York and Washington DC: China joining the World Trade Organization.

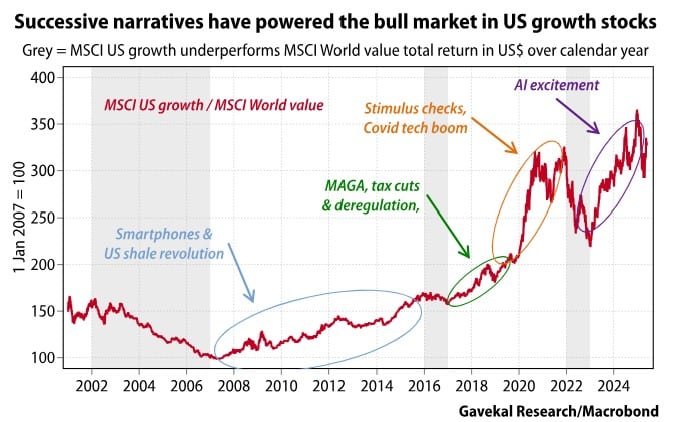

It was the same story with 2008. Back then, the US mortgage crisis felt like it might trigger an irreversible crisis of capitalism. However, the 2007-08 period also marked the start of the US shale oil production revolution, and the birth of the smartphone—two events that would drive financial markets for the following 15 years. The fact that the US would go from producing 5.5mn barrels of oil a day to 13mn/bbl a day in less than a decade (see my 2011 book Too Different for Comfort), that the US would enjoy a much lower cost of energy than any other major economy and the fact that major US corporates like Apple, Alphabet and Meta would end up controlling the broader smartphone ecosystem set the stage for the following 15 years of massive US equity outperformance.

1) What is the key event of 2025?

With all this in mind, if we project ourselves five or 10 years into the future, what will investors look back on as the key event of 2025? Consider the following possibilities:

Undeniably, it has been a busy year, with much to write about. In our modest way, we hope that through our published reports, videos, podcasts and seminars, Gavekal readers feel that we have stayed on top of these events. And to be sure, these developments all have a valid claim to posterity.

Still, if I were forced to make a choice as to what will go down as marking a key shift in the global macro environment, I would highlight three game-changing speeches delivered in recent months:

2) The folding of the US security umbrella and LatAm assets

I have already written on all three speeches. But the guiding thread between all three speeches is that the US is folding its global security umbrella. Most importantly, and to Erik Prince’s speech, the US is folding this security umbrella not because it wants to, but because in a new age of drone warfare, shooting million-dollar missiles at ten-thousand-dollar drones to protect billion-dollar ships no longer makes sense.

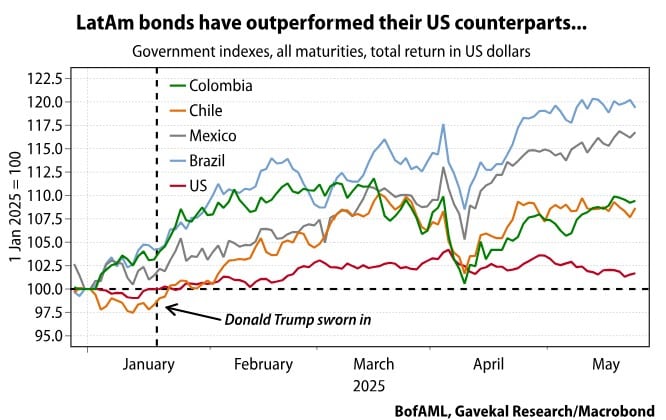

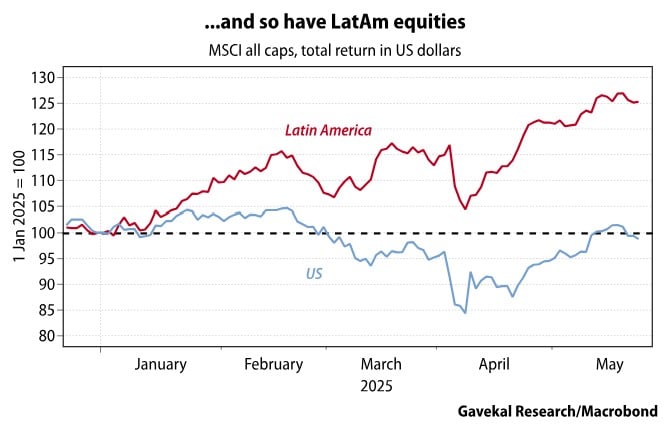

Concretely, this means that the US is now folding back unto the security of “Fort Monroe”, or the Americas. It also implies that the US will now aim to exert greater control over the broader Western hemisphere, from Greenland to Tierra del Fuego, and less elsewhere. This is inherently very bullish for Latin American assets. And sure enough, so far this year, LatAm bonds are outperforming all other bond markets quite handsomely, and LatAm equities are doing the same.

3) The impressive rally in non-US defense stocks

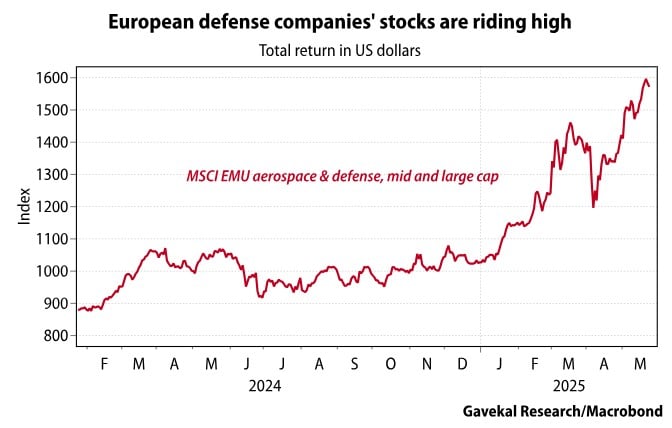

Interestingly, the immediate market response to the folding of the US security umbrella has been to bid up European and Japanese defense stocks. The logic seems obvious enough: in a world in which the US no longer provides free security, Western democracies will themselves have to cough up money to do so.

But is this just “first order” thinking? If it no longer makes sense for the US to send million dollar missiles at ten-thousand-dollar drones to protect billion dollar ships, should we expect Europe to build the same billion-dollar ships and million-dollar missiles? Moreover, if erstwhile US allies like Europe and Japan were to go out and spend a fortune on their armed forces, would this not be to mistake where their vulnerabilities truly lie?

Indeed, in the post-World War II era, the US essentially provided friends with two essential services. The first, and most obvious one, was the security umbrella. The second was the safety of global oceans.

4) Will commodity prices now diverge around the globe?

The fact that one could always count on commodities flowing from Latin America to Europe, or from Africa to China, or from Australia to Japan on oceans patrolled by the US Navy meant that, for the past 80 years, the world has essentially operated with one common price for all commodities. Sure, there have been small differences between oil prices in Japan and Brazil, or between copper prices in South Africa and South Korea. But these small differences essentially reflected transportation costs. When the price differences between countries or regions started to become too meaningful, firms such as Glencore, Trafigura, or Vitol would step in to arbitrage them away.

Fast forward to today and in a world in which the US is essentially signaling that it will no longer patrol the oceans or, at the very least, no longer patrol the oceans for free, can we still assume that the world’s major commodity prices will stay uniform across the globe? And if so, does this not have massive implications for reserve management?

5) Central bank reserve management in a riskier world

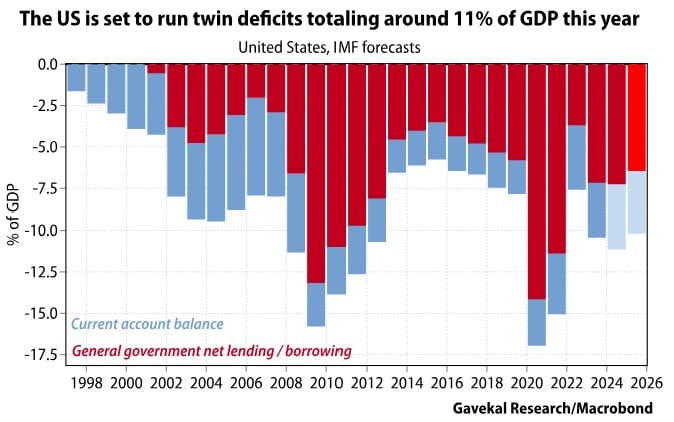

For most of the decades that followed World War II, and definitely in the decades that followed President Richard Nixon’s breaking of the US dollar’s peg to gold, the US has run large twin deficits.

This situation essentially meant that the US kept exporting US dollars to the rest of the world. And when the rest of the world earned these excess US dollars, the default mode was to send the dollars back into the US by buying US treasuries. This made ample sense. For most countries, saving in treasuries meant that if a crisis occurred (maybe a tsunami, an earthquake, a civil war or even a full-on war), they could always count on the US Navy to deliver the food, energy, or weapons (as needed) by simply transforming US treasuries into the above goods and commodities.

However, if one can no longer count on the US Navy to deliver such goods, and/or the US states that, in a crisis, it will not hesitate to squeeze every pound of flesh from the country on the ropes (e.g. the Ukraine minerals deal) or, worse yet, the US adopts a confrontational stance against countries that run the biggest trade surpluses (e.g. China), then saving in US treasuries may no longer be such an obvious course of action.

Hence the unfolding sell-off in US government bonds, and in the US dollar. Even as Trump boasts of trillions of dollars set to leave the Middle East for US shores, bonds and the US dollar are still struggling.

To illustrate the above point, let us go through a hypothetical scenario.

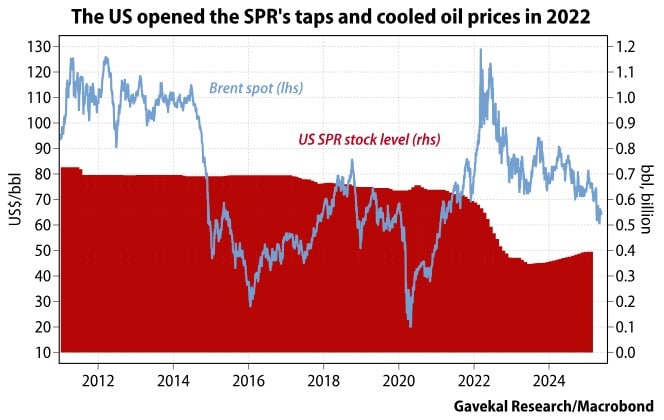

In 2022, when Russian troops entered Ukraine, the oil price promptly surged from US$70/bbl to US$130/bbl. For the US, this was not that big a deal. Indeed, with the US being energy self-sufficient, rising oil prices just meant moving money from blue states (New York, Michigan, Illinois) to red states (Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Alaska, North Dakota). Meanwhile, for Europe, Japan, South Korea and most American allies, the spike in oil prices risked pushing fragile economies into recessions. Joe Biden’s administration duly released oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and oil prices rapidly came back to more affordable levels.

Now let us imagine that, for whatever reason, a similar price spike happens in the near future. Consider two different ways that Trump could respond:

Given everything we have seen in recent months, does not the latter option seem far more likely?

This brings us to the quandary that should keep every European and Asian policymaker awake today, namely whether the big risk in the coming years is that Russian or Chinese troops end up walking down the streets of Paris, Berlin, Seoul or Tokyo. Or alternatively, whether in the next energy crisis, triggered by who knows what, their own countries find themselves cut off from energy supplies.

If the bigger risk is the Russian/Chinese troops, then spending one’s excess dollars on weapons (that may already be obsolete) may conceptually make sense. Otherwise, spending money to rebuild dated energy grids, building up commodity independence, preparing stockpiles of important materials (whether oil, soybeans, copper, nickel, uranium or whatever else individual countries may today be looking abroad for) would seem to be a much better use of capital.

6) Building up inventories across the board

This unfolding “trade war” uncertainty, combined with the increased likelihood that the US is done patrolling the world’s oceans for free, means that all economic actors will have to build up bigger inventories: countries will have to accumulate inventories of key resources; companies will need to maintain higher inventories of spare parts and consumer goods; even individuals may wish to have better stacked pantries, spare electronics, and perhaps even spare vehicles.

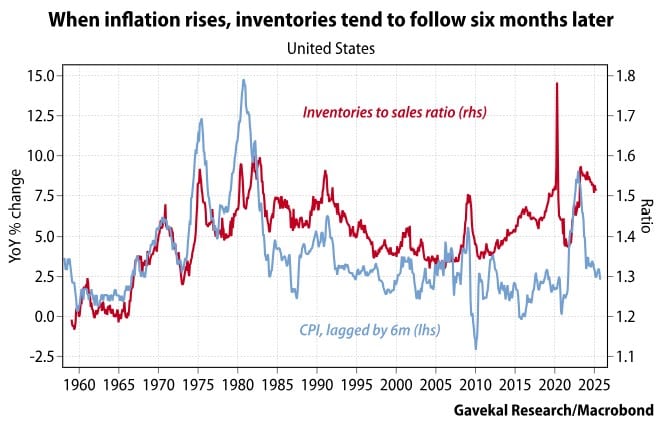

This raises the question: if the “just in time” era seen in the past 30 years was inherently deflationary, will the “just in case” period that is unfolding be structurally inflationary? Perhaps not, if only because the relationship historically seems to have gone the other way around: when inflation accelerates, six months later companies typically start to raise inventories.

But at the very least, it will mean more volatile growth.

Indeed, the inherent problem with inventories is that they add complications to business management. Goods and commodities can be bought at the wrong time. Companies can also order the wrong things. This can mean inventories having to be liquidated for a loss. It adds up to inventories adding risk to a business and distracting the management.

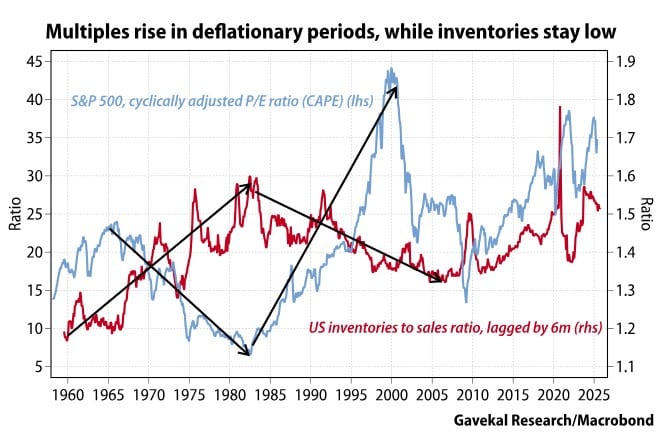

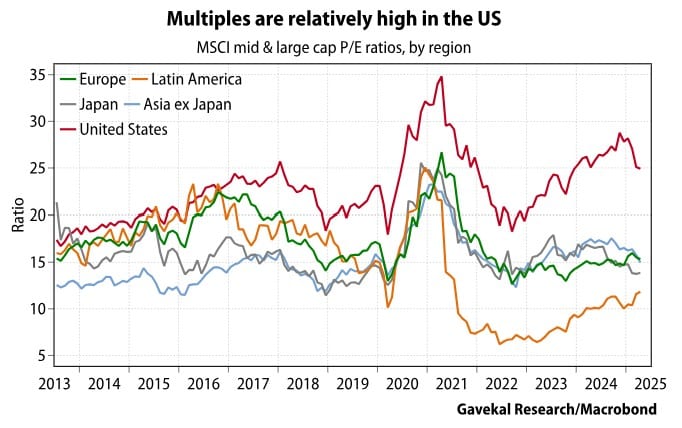

This is partly why in inflationary periods (when company managements spend much time worrying about inventories), equity-market multiples tend to be low, and in deflationary periods (when inventories are “just in time”), multiples tend to be high—as shown in the first chart below. Today, multiples are high in the US, and decently low everywhere else, as seen in the second chart.

Conclusion: winners and losers

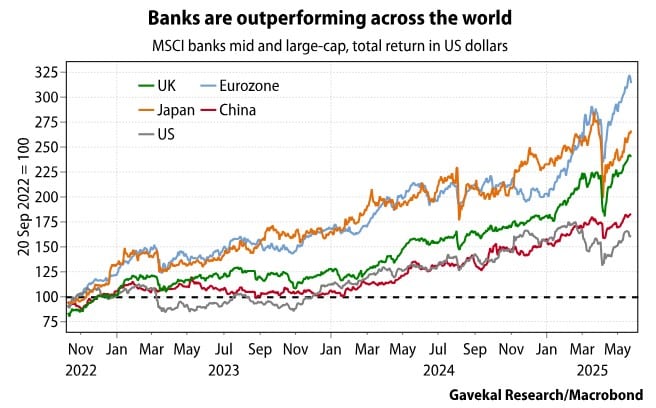

If the above takeaway—namely that the US is folding its security umbrella and withdrawing from patrolling the world’s oceans—is right, it would seem that the obvious beneficiaries should be:

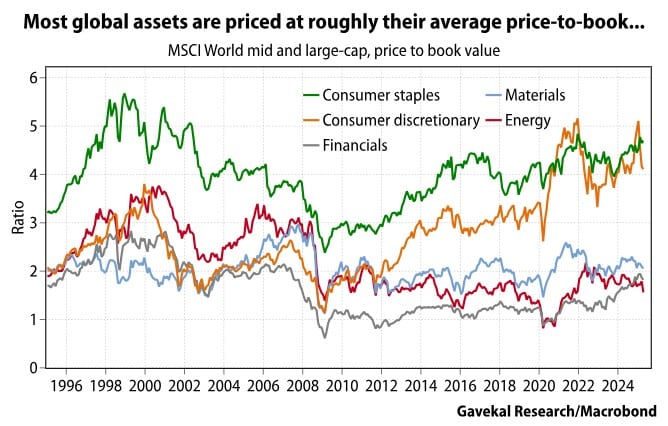

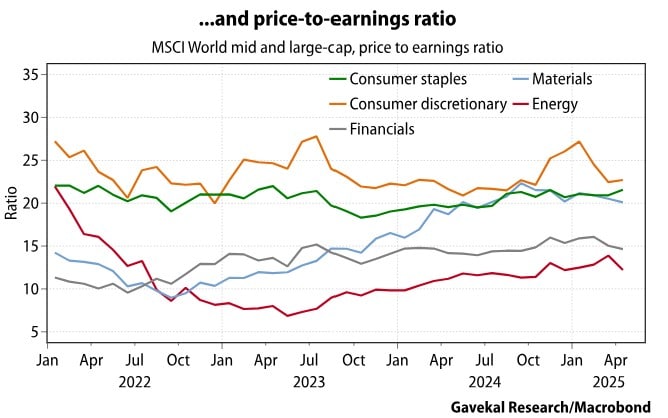

This list is not meant to be exhaustive. There are likely to be many winners and losers if the US no longer stays involved in the Middle East to ensure that Europe and Asia remain provisioned with oil. The good news is that, as of now, investors do not need to pay up for the above assets. Most are trading at roughly average, or slightly below average, historical valuations.

DISCLOSURE: Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.