By Will Denyer

For the first time in this cycle, Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell cheerily intoned on Wednesday that “a disinflationary process has started”. Accordingly, the Fed further slowed the pace of tightening—hiking the main policy interest rate by 25bp (to just under 4.75%), as opposed to prior increments of 50bp and 75bp. So given this apparent disinflationary dynamic, why is Powell and his policymaking committee still signaling “ongoing increases” in rates?

First, consider the growing evidence of a slowdown in US inflation (a.k.a., disinflation). The Fed’s favored measure—the price index on personal consumption expenditures—is already trending back toward 2%. Over the last three and six months, annualized PCE inflation has averaged 2.1%, down from 5.0% over the past year, to put it basically on target.

While headline inflation can be volatile, most indicators suggest this disinflation is not “transient”. The less noisy core PCE index is trending lower, averaging an annualized 2.9% over the past three months, down from 3.7% in the past six months and 4.4% in the last year. While Fed vice chair Lael Brainard and other policymakers do not see evidence of an upward wage- price spiral, they must take comfort in the recent slowdown in wage growth. The best measure—the employment cost index—released earlier this week showed wage growth slowing to 5.1% year-on-year in 4Q22, down from 5.2% in 3Q and 5.4% in 2Q. Add in another sub-50 reading from the ISM manufacturing PMI (at 47.4 for January), and this week’s data generally supports the message that existing policy and financial conditions in the US are successfully weighing on demand and price pressures.

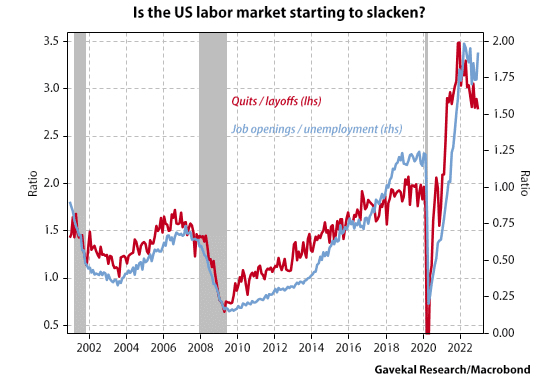

This week’s data releases did throw one spanner in the works. Job openings measured by the JOLTs release jumped in December, reversing much of the downtrend seen in the last eight months. This matters since one of Powell’s favorite indicators of labor market supply and demand is the ratio of job openings to unemployment. If this reading marks the start of a new trend— whether stable or rising—it implies a US recession may not yet be in the works and the Fed may need to keep hiking interest rates.

However, there is reason to think the jump in JOLTs is noise. Private-sector measures of job openings (job postings on Indeed.com) continue to decline. Wage growth is slowing, and more forward-looking data within the JOLTS report continues to point to a softening labor market.

Consider the ratio of quits to layoffs, a handy leading indicator of Powell’s favorite job openings-to-unemployment ratio. Lots of resignations show workers to be confident, as people usually quit a job when a better opportunity awaits. In contrast, lots of layoffs indicate wary employers, since a downgraded outlook often calls for cost-cutting. Put together, a decline in the quits-to-layoffs ratio signals falling confidence from one or both sides of the employment contract and a softening labor market. This ratio peaked in December 2021, foreshadowing a rollover in job openings/unemployment three months later. With this measure still falling in December, the rebound in the job openings-to-unemployment ratio could be a head fake.

While labor market data is still solid, recessions usually start with employment and wage data rolling over from robust levels. Hence, there is good reason to pay as much attention to the direction of travel with labor market data as to levels. So, why is Powell and his committee signaling ongoing rate hikes, with two or more still to come? There are three probable, and not mutually exclusive, explanations for his approach:

With the policymakers’ statement anticipating “ongoing increases” in the target rate, the base case must be that the Fed hikes at least one more time. However, there is good reason to expect US growth and inflation data to keep heading toward a disinflationary bust—and possibly a recession. If so, the Fed may need to revise its stated plans.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.