Dear Clients and Readers,

This week, we are presenting a thought-provoking article from Gavekal Research's Co-Founder, Anatole Kaletsky. In his piece, Anatole shares a contrarian take on the current outlook for the US economy. While we don't necessarily agree wholeheartedly with his forecast, his viewpoint bears consideration, especially as the consensus for a recession continues to swell. Today's jobs report, which outpaced expectations and signaled that the labor market remains robust despite recession fears, is certainly notable given Anatole's take on where the economy is heading. Please enjoy.

By Anatole Kaletsky

The markets are beginning to trade as if a US recession is imminent in the next few months—or maybe is already starting. As a result, fears of sustained inflation and unexpected monetary tightening have almost completely disappeared. This new market consensus is completely wrong, at least in my view. I believe there is almost no chance of a US recession this year or early in 2023. (The prospects for Europe are a different matter because of the self-inflicted damage from the Ukraine war and Russian sanctions.) Investors should therefore use the present recession panic to increase their inflation hedges in commodities. The last thing they should do is succumb to the recession panic and extend bond duration.

Last month, I laid out my objections to the surprisingly widespread optimism among investors about recession and also some reasons for confidence that US and global expansions will continue well into next year (see Five Fallacies About Inflation and Three History Lessons On Protecting Against Inflation). But the mounting frenzy of recession forecasts, and the market pricing which implies that an early US recession is becoming conventional wisdom, makes me feel that it is worth updating and consolidating these arguments in one place. So, here are my main reasons for disregarding US recession fears and believing that the recent correction in commodities and related assets is a great buying opportunity, while the rebound in bond prices is a classic “mug’s rally”. (Actually, I think that recession “fears” should really be described as “recession hopes”, since an early US recession would be the best possible tonic for curing all global inflation ills and for achieving a quick return to the low interest rate, moderate growth Goldilocks conditions that we all got to know and love until the Ukraine war.)

1. Monetary policy

Monetary policy in the US is not remotely restrictive enough to cause a recession because interest rates are still deeply negative in real terms—and a recession has never begun at a time when real overnight or real 10-year yields were lower than 1%, never mind below zero or at -7.6% and -5.7%, respectively, which is where they are today.

Of course, this statement depends on the definition of “real” interest rates. Many investors these days like to define a real interest rate by starting not with the overnight rates that prevail today but by those predicted a year from now. They then subtract from this market prediction another market prediction: of average inflation in the next 10 years or five years. This approach defies both common sense and economic theory.

The way any real borrower calculates real rates is by taking the nominal rates for a given tenor and subtracting from this either the reported (backward-looking) inflation data, or an estimate of inflation expected during the lifetime of the loan. Short-term nominal rates should therefore be deflated either by reported inflation (as in my chart below) or by some guesstimate of expected inflation one year ahead (which is usually similar to the historical 12-month rate). Five-year and 10-year yields could be deflated by five-year or 10-year inflation expectations if any reliable data existed on these, which it does not. On this kind of calculation, monetary policy today, far from becoming restrictive, is still super-stimulative. And it will remain stimulative at least until the end of this year, because even if the federal funds rate rises to 3% or 3.5% by then, backward-looking inflation will still be well above 4% and expected inflation in the 12 months after that is unlikely to be much lower.

2. Economic activity lags monetary policy

Time lags are the second reason to dismiss the idea that the Federal Reserve has already made a “policy mistake” by tightening money too much, or is about to do this. The lag before economic activity responds to tight money—as measured, for example, by the time between yield-curve inversion and the start of a recession—has never been shorter than nine months, and has usually been a year or longer (see the chart overleaf). Judging by this experience, even if monetary policy turns restrictive by the end of this year in the sense of the yield curve inverting (which I think is unlikely), the earliest plausible date for a US recession would be late 2023. If we then add another six- to 12-month lag before structural inflation is reversed by the rising unemployment caused by recession, a substantial easing of underlying US inflationary pressures (as opposed to a temporary reversal of some temporary base effects) seems unlikely until the middle of 2024.

The markets, however, have suddenly become confident that inflation and economic activity will both slow abruptly within the next few months, even before monetary policy has seriously tightened. This confidence is based on the belief that the mere expectation of positive real interest rates sometime in the future will be sufficient on its own to subdue labor and business pricing behavior. Thus, instead of the “long and variable lags” that have always delayed the disinflationary effects of monetary tightening in the past, investors are now assuming that the lags have not just been shortened; but that they have turned negative. This is possible, in the sense that almost anything is possible in economics, which is an unpredictable business. But if a recession starts this year, even before real policy rates have turned positive, it would be a spectacular case of “this time is different”.

3. Economic indicators

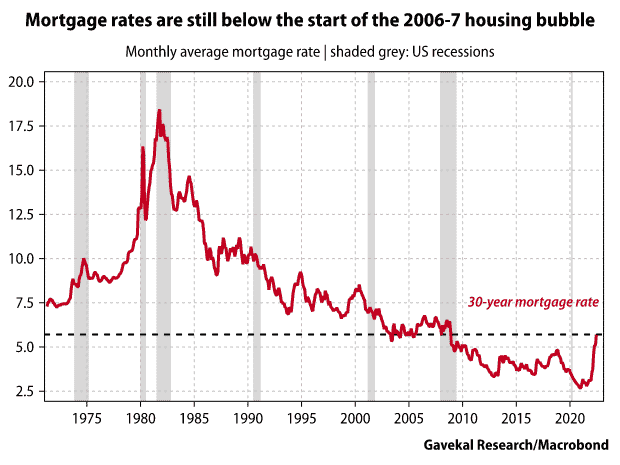

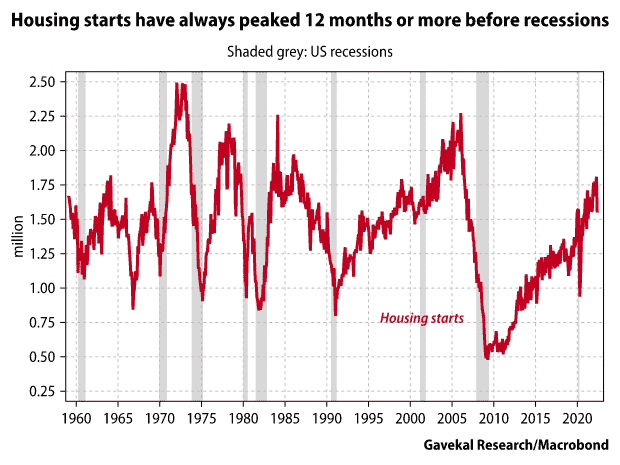

Indicators of US economic activity, while they mostly point to a growth slowdown, are not yet remotely weak enough to signal a recession within the next six to nine months. House sales, for example, have slowed significantly and housing starts have fallen in response to rising mortgage rates; but housing conditions are still well above levels seen at the start of previous recessions. And 30-year mortgage rates, although they have doubled in the past nine months, are still lower than they were at the start of the 2006-7 housing bubble.

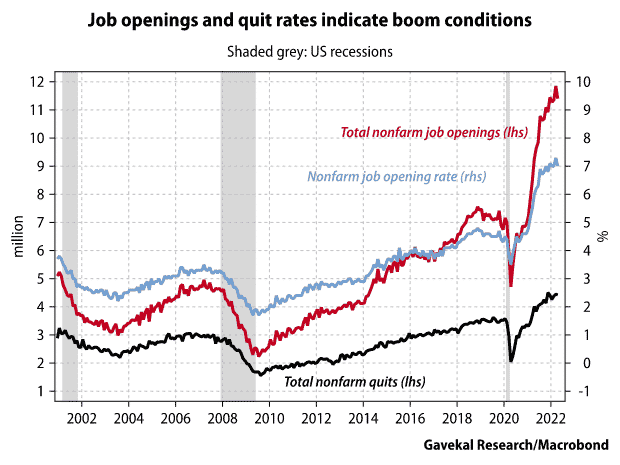

Similarly, commodity prices, retail sales, business investment, leading indicators and purchasing manager indexes are mostly still high enough to indicate steady growth—or even unprecedented boom conditions in the case of labor indicators such as job openings and quit rates.

4. Economic activity lags economic indicators

“Long and variable lags” apply to economic indicators as well as monetary policy. Even if some real economy sectors such as housing continue to weaken rapidly in the coming months, my argument above on the lag between monetary policy and economic activity also applies to economic indicators and actual activity. For example, peaks in the housing market have always occurred more than 12 months before the start of previous recessions.

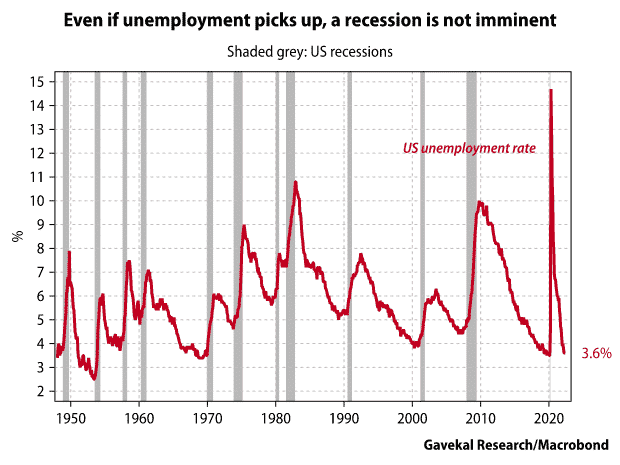

This is also true of troughs in the unemployment rate. So, even if the US labor market data published this week show the start of a sustained increase in unemployment, which is very unlikely, past experience would point to a recession starting in the second half of 2023.

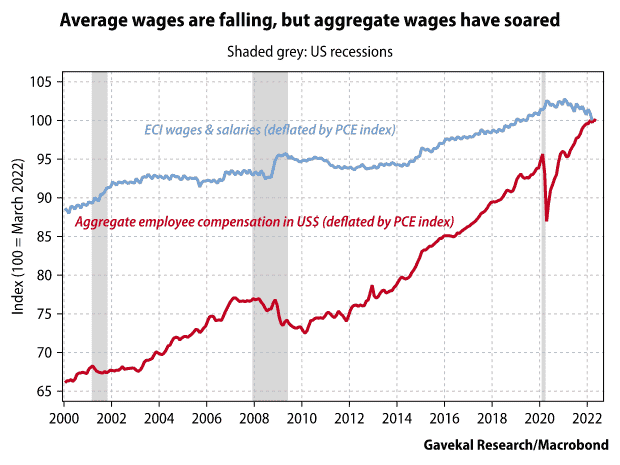

5. Inflation is not a growth killer

High inflation does not automatically curb growth by reducing real wages. While many investors now seem to believe that “high prices are the cure for high prices,” I see two reasons why this adage is wrong, or at least premature. Firstly, the reduction in real wages due to inflation has been more than offset, at least until very recently, by the strong growth of employment. As a result, aggregate wages and salaries have grown by 12.4% in the past two years, even after inflation, despite the fact that average individual wages (as measured by the quarterly Employment Cost Index) have fallen in real terms by -2.5% (see chart below). Since GDP is driven by the aggregate spending of all consumers in the economy, not by the spending of the average individual consumer, a recession is unlikely when employment is growing so rapidly that it offsets the effect of inflation on individual workers’ spending power.

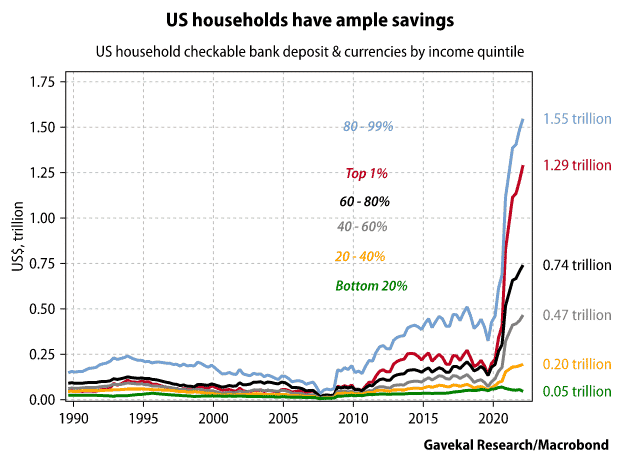

Secondly, last year’s huge fiscal expansion created an unprecedented increase in US personal savings, boosting household’s checkable bank deposits by US$2-2.5trn above the pre-Covid trend. This increase in fully-liquid household assets, equivalent to roughly 10% of US GDP, allows US consumers to continue spending briskly, even as their real incomes decline due to inflation. How long this process will continue is impossible to predict, but data published by the Fed suggest that all but the poorest US households (whose spending has very limited impact on total GDP) still have an ample cushion of excess liquid saving with which to offset the effect of inflation on their spending power.

6. Chinese reopening

If this happens, the panic about recession will quickly vanish. Instead, the markets will again be overwhelmed by fears of sustained inflation, or much higher interest rates than central bankers have yet suggested, and probably both. Since these fears will be fully justified, investors who are now praying for a quick recession that will bring back the world of Goldilocks and “magic money trees” will need to focus instead on what is likely to be the central challenge of this decade: how to restructure portfolios for an era of permanently troublesome inflation and higher interest rates.

Finally, my assumption is that China will fully unlock its economy by the end of this year, or early in 2023. Since China now has a bigger GDP than the US, when measured at purchasing power parity, the resulting boost to global economic activity and trade could match that of the 2021 US reopening boom. If China duly shifts from its current Covid containment or eradication strategy to more of a Covid toleration approach at a time when the West is still enforcing sanctions against Russia, energy and commodity prices will again explode upwards, as they did at the start of the Ukraine war.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.