“A bull market is like sex. It feels the best just before it ends.”

-The great, late BARTON BIGGS

“Wall Street is a place where highly confident got to work. Unfortunately overconfidence makes it hard for many to hold on to the possibility they might be wrong, with potentially painful consequences.”

-The great and not late PAUL SINGER, CEO of Elliott Funds, among the best performing hedge funds of all-time.

“The further a society drifts from the truth, the more it will hate those who speak it.”

-GEORGE ORWELL

By David Hay / CIO, Evergreen Gavekal

The sampler. This week’s edition of the Evergreen Virtual Advisor is a trilogy of recent short articles by three of my favorite thinkers at our partner firm Gavekal. The first is a timely essay by Tan Kai Xian (fortunately he is kind enough to let us refer to him as KX!). As you will soon read, he reflects on last week’s embarrassing flame-out of Obamacare reform and discusses the potential implications for tax reform. “Ryancare,” as some wags call it, was pulled before it went down to almost certain defeat—a casualty of the GOP’s infighting on what was one of its signature campaign promises. Who could have possibly not known healthcare reform was so complicated?

The relevance to the stock market is that Mr. Trump’s honeymoon period appears to be over. Certainly, the can-do-anything aura that he has exuded—and that equity investors have lapped up—is fading fast. But you’ve got to give the bulls credit; they have immediately shifted their buy-baby-buy thesis to tax reform. After all, they confidently assert, it’s much more important to the stock market than a silly old healthcare revamp.

Yet, as KX points out, the path to a comprehensive make-over of America’s fantastically byzantine tax code seems to be as daunting as repealing and replacing the unAffordable Care Act (ACA). He makes the important observation that, without the trillion-dollar savings (over 10 years) ACA/Obamacare reform was supposed to produce, corporate tax cuts will be less—to use a relevant word—affordable. Further, KX states that the Border Adjustment Tax (BAT) has been championed as another offset to slashing business tax brackets. However, this is proving to be nearly as contentious within the Republican party as was “Ryancare.”

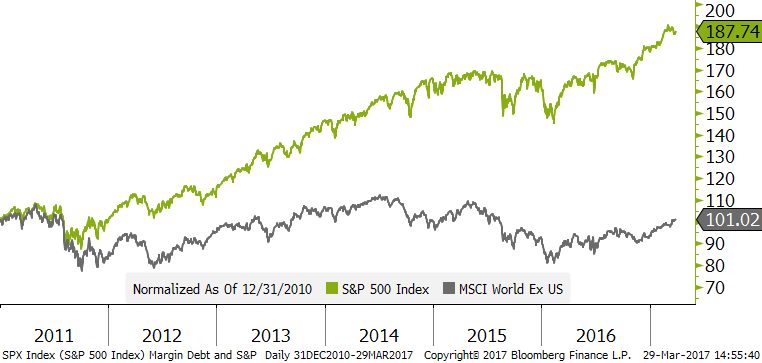

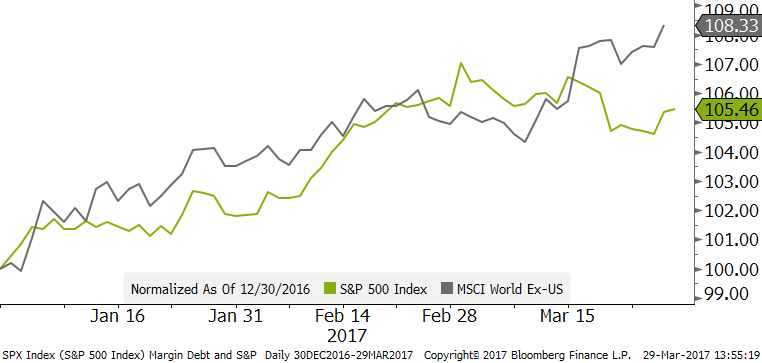

The sudden mood shift among those under the spell of Trumphoria has put notable downward pressure on the beneficiaries of the so-called reflation trade. Since we’ve been highly skeptical of the logic behind the bullish story for steel and heavy machinery stocks—among others—we can’t say we’re heartbroken by this development. Nor are we surprised by the narrowing spread between short- and long-term interest rates, otherwise known as a flattening yield curve. In fact, this, along with a rally in the widely-reviled Treasury bond market, was a main theme of our March 17th EVA. We also heartily concur with KX’s view that overseas markets will continue to play catch-up to the S&P 500, after massively trailing the U.S. market for what feels like eons. And so far, this year, international stocks have indeed bested their US equivalents.

S&P 500 HAS NEARLY DOUBLED THE RETURN OF GLOBAL MARKETS EX-US SINCE 2011...

...BUT IT'S A DIFFERENT STORY THIS YEAR

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

To give further credit to the never-say-die attitude of Wall Street optimists—who continue to go to great lengths to rationalize one of the most expensive stock markets of all-time—they have come up with another reason not to sweat last week’s Trump-uppance: earnings. Their reasoning is that, suddenly, corporate profits are poised to soar.

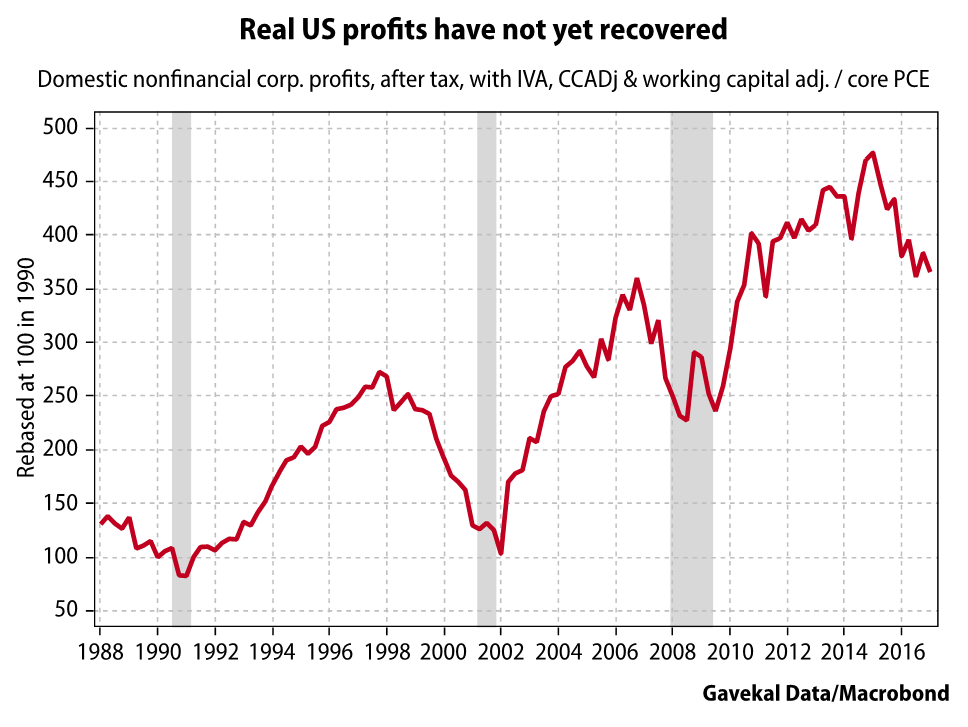

In fact, prior EVAs have commented on the end of the profits recession that began in mid-2014, which was at least partially responsible for the two brief, but sharp, corrections that hit stocks in mid-2015 and, again, at the start of last year. However, in the second part of this issue, my close friend Will Denyer challenges the idea that the earnings contraction is over. His logic is based on using the government’s own inflation-correction measures: capital consumption and inventory valuation adjustments.

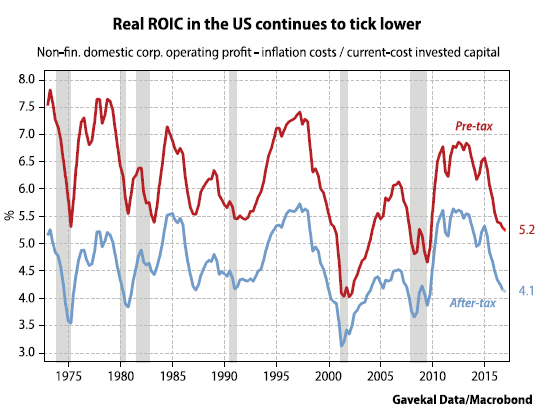

Without getting into the nitty-gritty, suffice to say that on this basis profits continue to head south like retired snowbirds in January. Moreover, the same is true of real, or after-inflation, Returns on Invested Capital (ROIC). In the latter case, these have already declined to a greater degree than during the Great Recession! As you can see, there is no evidence of a trend change, at least thus far.

Source: Gavekal Data/Macrobond

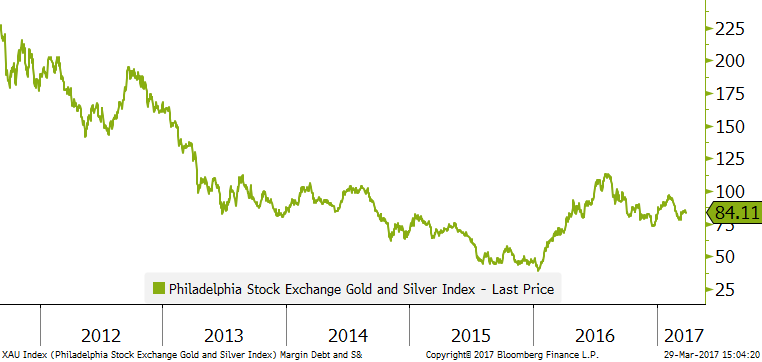

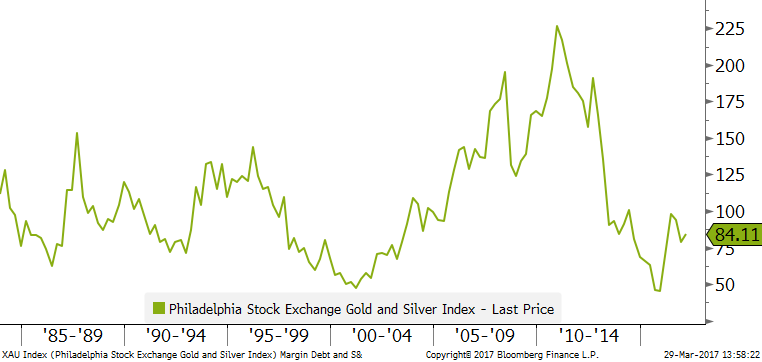

Last but not least is a concise note from my great friend and Gavekal’s primary founder, Louis Gave. In it, he wrestles with ways to protect client portfolios from what will eventually be an end to this most elderly bull market, of which the US has been, by far, the best in show. One option he presents, as similarly outlined by KX, is to tilt toward long-lagging international markets. Another, is to mix in exposure to gold mining stocks which have been laggards (with a capital “L”) since the earth began to cool. Certainly, post-2011, miners have radically underperformed the S&P 500 (despite a spirited rally last year). In fact, the Gold and Silver Index is lower today than it was when it was created in 1979!

PHILADELPHIA STOCK EXCHANGE GOLD AND SILVER INDEX (2011-PRESENT)

PHILADELPHIA STOCK EXCHANGE GOLD AND SILVER INDEX (1979-PRESENT)

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

Due to this pattern of negative returns, the days of apocalyptic pundits urging investors to ditch all their financial assets, and load up on bullion and gold mining stocks as a hedge against the binge-printing of central banks, are long gone. Both gold and miners seem to be caught in a wide trading-range; in other words, they are going nowhere fast. Therefore, bullion offers nervous bulls some cheap insurance coverage.

As Louis notes, bonds, at least of the gilt-edged variety, have consistently been excellent counter-weights to stocks. This is why balanced portfolios have fared much better than all-equity portfolios since the dawn of the new millennium, particularly on a risk-adjusted basis. There are valid concerns, though, that with yields so low, the protective effect may be greatly diminished. This would be particularly true should inflation surge, a possibility that would be troublesome for both stocks and bonds. Yet, gold mining stocks are world-beaters when inflation busts out, offering a nifty “double-indemnity”, protecting both sides of a conventional balanced portfolio.

Presently, investors care little about downside protection and are much more focused on capturing as much as they can from this ancient bull market. But, as sure as night follows day, that attitude is certain to change—and in a big way.

AFTER THE HEALTH CARE REFORM FAILURE

By Tan Kai Xian

The Republican drive to repeal and replace Obamacare failed ignominiously last Friday. Together, President Donald Trump and House Speaker Paul Ryan were unable to muster enough support to pass the new health care bill through the House of Representatives. Bowing to reality, they pulled the vote. If there is a positive element to this failure, it is that both the administration and Congress will now shift their focus to tax reform. However, the setback on health care—the new administration’s first big legislative test—has badly damaged the confidence of US households and businesses in Trump’s ability to push his reform agenda through Congress. Investors’ already dwindling belief in the sustainability of the Trump trade is only likely to diminish further as a result.

The obstacles to tax reform are at least as great as those that blocked the health care bill. For one thing, without the projected fiscal savings from replacing Obamacare, the backers of tax reform will have an even bigger fiscal hole to fill when they table their bill. For another, the White House view of the border adjustment taxes proposed by the House Republicans remains unclear. With US retailers lobbying aggressively against the idea and a sizable number of Republican Senators publicly expressing concerns about the potential impact, the headwinds are stiff. As a result, it is now abundantly clear that fiscal and regulatory reforms are going to take a lot longer to accomplish than many investors previously hoped.

That means the post-election optimism on US growth prospects is likely to moderate further. Granted, the hard data, such as industrial production, have shown a modest improvement lately. But, the rebound has been less strong than indicated by soft data, such as sentiment indexes. If the soft data now eases, hopes for a strong cyclical upturn in growth will dissipate.

That will further dampen enthusiasm for the Trumpflation trade, which has waned lately as expectations for higher nominal growth have eased. The diminishing base effect from last year’s rebound in oil prices and slowing bank credit growth both point to moderating US inflation. In response, the US break-even inflation rate has started to fall, the yield curve is flattening, the outperformance of bank shares is reversing, and the US dollar has weakened from December’s highs. Last Friday’s blow to the administration’s reform agenda only increases the odds of a further reversal in the Trump trade.

That’s clearly a headwind for US risk assets. However, it also means that both structural and cyclical forces in the US now increasingly favor the outperformance of emerging market assets. With the near-term prospect of stimulative US reforms much reduced, the chances of a steeper monetary tightening path from the Federal Reserve are also diminished. As a result, the risks of a higher long bond yield and a stronger US dollar—both major concerns for emerging market investors—have receded.

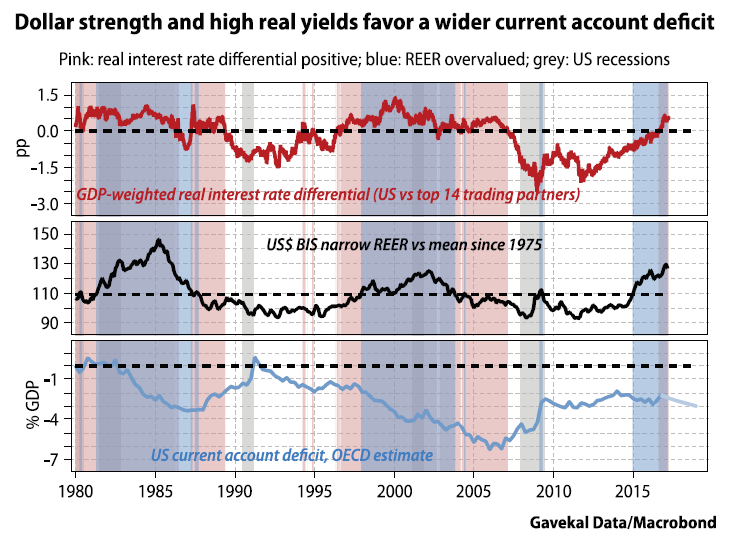

On top of that, the US current account deficit is widening. The US trade deficit came in at US$48.5bn in January, the biggest gap since March 2012. With US consumers buying more overseas goods and services, this is a clear sign that additional US dollar liquidity is flowing abroad. For two reasons, this is likely to mark the beginning of a new downward trend in the US current account:

The caveat here is that a wider current account deficit would conflict with Trump’s policy goals. The risk, therefore, is that the administration could pursue disruptive measures to prevent the current account deficit from blowing out, such as coordinated currency intervention or outright import tariffs. However, with the focus of the White House now turning to domestic tax reform, a unilateral attempt by the administration to constrain the current account deficit remains a distant prospect, at least for now. Given the strong pick-up in international demand, and the cyclical dynamic in the US, investors should look beyond US shores for investment opportunities.

Source: Gavekal Data/Macrobond

Source: Gavekal Data/Macrobond

THE PROFIT ILLUSION

By Will Denyer

Inflation has a way of making things look better than they really are. This is especially true of corporate profits. After a dismal first half last year, S&P 500 companies reported an earnings recovery in 2H16. In the final quarter, they posted profit growth of 6% YoY (with or without financials). Alas, this recovery appears to be a mirage, caused by accelerating inflation. Using official flow of funds data for the domestic non-financial corporate sector, and adjusting for the effects of inflation, I find that US corporate returns, in real terms, were flat in the second half of 2016 and actually ticked down in 4Q. There has been no recovery in profits.

One might think that 6% nominal profit growth, in the context of 1.5-2% inflation, would give positive profit growth in real terms. It does not. It is not enough simply to deflate headline profits by an inflation index. The trouble is that conventional accounting does not adjust for the rising cost of replacing capital, such as depreciating assets and inventories. Inflation pushes up revenues, while depreciation and the cost of goods sold are deducted based on historical costs. This makes profits look greater than they really are. This problem was articulated over 100 years ago by Ludwig von Mises, in his classic book, The Theory of Money & Credit:

“If the value of money falls, ordinary book-keeping, which does not take account of monetary depreciation, shows apparent profits, because it balances against the sums of money received for sales a cost of production calculated in money of a higher value, and because it writes off from book values originally estimated in money of a higher value items of money of a smaller value. What is thus improperly regarded as profit, instead of as part of capital, is consumed by the entrepreneur or passed on either to the consumer in the form of price reductions that would not otherwise have been made or to the laborer in the form of higher wages, and the government proceeds to tax it as income or profits. In any case, consumption of capital results from the fact that monetary depreciation falsifies capital accounting.”

Thankfully, the US flow of funds statisticians provide their own measures of corporate profits, adjusted for changes in the replacement costs of fixed capital and inventories (named “capital consumption adjustments” or CCadj, and “inventory valuation adjustments” or IVA). We then extend this logic one step further, applying what we call a “working capital adjustment”—which accounts for the fact that, like inventories and fixed assets, working capital requirements also rise and fall with inflation. Thus, during periods of inflation, a portion of inflows need to be added to working capital rather than treated as profit and consumed. After making these adjustments, whatever profit is left over can then be deflated by a price index. The resulting measure of real profits fell dramatically in 2015 and was basically flat over the course of 2016. If anything, profits have kept falling marginally, with 4Q16 profits actually down a touch versus 3Q and versus a year prior. There has been no recovery.

The result is that return on invested capital in the US continues to slide. And with interest rates across the curve having risen in recent months, my various Wicksellian spreads between the return on capital and the cost of capital have narrowed further. Although the Fed softened its hawkish tone, it still hiked rates, and it plans to hike further this year. Investor hopes are high that these increases will be more than offset by a rebound in returns—thanks to rising animal spirits and possible policy reforms. Perhaps. But for now those are just hopes. The facts on the ground still call for caution.

With the latest data, my Wicksellian spreads* are not yet flashing red. But they are now glowing a very dark orange, as the most topical spread, based on the Fed Fund rate, suggests. According to my model, equity risk exposure should now be reduced to roughly one quarter of full risk-on levels. Instead, investors should overweight cash and treasuries (possibly throwing gold and gold miners into the mix, as argued by Louis below).

* “Any Wicksellian analysis starts with the difference between the market interest rate and the natural interest rate. The market rate…is the real rate on long-dated seasoned industrial bonds, which is [arrived at] by deflating the nominal yield on Baa-rated bonds by the seven-year moving average of US CPI inflation. And as a reliable proxy for the natural rate…simply take the real year-on-year growth rate of US gross domestic product. The difference between the two is the Wicksellian spread.” (For a full tutorial on the Wicksellian spread, please click here.)

HEDGES IN A BULL MARKET

By Louis-Vincent Gave

It is hard to find an equity market anywhere that is not in bull market territory. This much is clear from a quick look at the Gavekal TrackMacro grid. Simply put, not a single country is now flashing red. You have to go back to the Spring of 2014 for such a benign global macro backdrop.

This isn’t to say that equity markets face no risks. The March 15th election results in the Netherlands may suggest that the populist wave in Europe is waning, but political risk remains high. In the US, policymaking is increasingly haphazard. In China, while stability will undoubtedly be maintained in the lead-up to the Party Congress this fall, it remains unclear what type of leader Xi Jinping aims to be, and for how long? This last point especially matters given Pyongyang’s bellicosity.

And that’s before the potential for a chaotic French parliamentary election is considered, as the historic parties of government (Les Republicains and the Socialist Party) both seem to be imploding. Or the fact that the mess in Italian banks is unlikely to be dealt with by a government with little popular backing.

Yet bull markets famously climb a “wall of worry”. The fact that equities are trending higher despite so many worries can be explained variously: (i) the fact that, in recent years, central banks have created so much liquidity, (ii) the growing realization that under a mercantilist US president a US dollar short-squeeze may not unfold, or (iii) recognition that instead of imploding, Chinese growth is busy reaccelerating.

It almost doesn’t matter for, as popular wisdom states, success has many fathers. Still, as global equity markets continue to make new highs, the prudent investor is left wondering how to hedge? For years, the simple answer has been to buy long-dated bonds. As equities tank, bonds always thrive; looking back at every -15% or more annual drop in the S&P 500 since 1962 shows a corresponding 10% or more rise in bond prices.

This characteristic of bonds is the bedrock of most “risk-parity funds” and the reason why disciplined balanced funds have, over long periods, delivered solid risk-adjusted returns. At least, until the past year when the prevalence of very low bond yields almost everywhere caused bonds to hit many portfolios with more volatility and negative returns. This begs the question of whether bonds remain the most efficient portfolio diversifier.

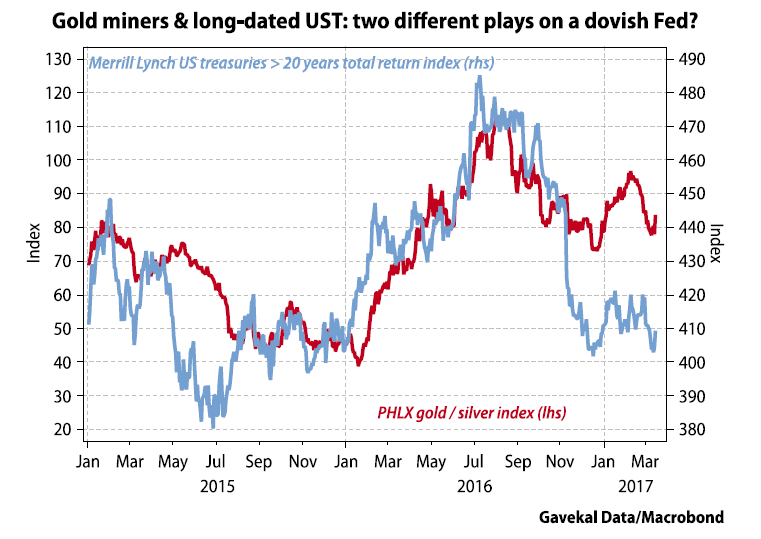

As such, consider the chart below which in recent years shows a surprisingly strong correlation between gold miners and long-dated bonds. Historically, these two assets have tended to move in opposite directions, with accelerating inflation being good for gold, and bad for bonds, and vice versa. Now, they seem to be moving together, based on market perception of what the Federal Reserve will do next.

Source: Gavekal Data/Macrobond

Source: Gavekal Data/Macrobond

Take the trading action on Wednesday, March 15th: the Fed came out sounding marginally more dovish than anticipated, bonds, stocks and bullion was quickly bid higher. In particular, the Philadelphia Gold and Silver index (XAU) surged 7.4%. Which brings us back to the risks lurking in this bull market’s shadows and the best hedges on offer.

The first risk has to be that higher inflation proves to be more than a dead-cat bounce as prices grind higher on central bank willingness to stay behind the curve, while government purse strings stay wide open (Trump in the US, May in the UK, Abe in Japan, possibly Schulz in Germany). In such an environment, there may, of course, be no need for an equity portfolio hedge; at least for a while. Instead, investors would look to own “price monetizer” companies, along with markets whose valuations have been decimated by deflation (Japan, Italy, Spain, Greece). In such an environment, gold miners seem sure to outperform bonds.

The second risk has to be that equity markets are leaning too far over their skis, and instead of rebounding, growth, in the near term, disappoints (whether due to slowing bank loans, or reduced capital spending given fiscal and regulatory uncertainty). But if this scenario were to occur, how would the Fed react? Most likely by sounding dovish and, as Wednesday’s trading action showed, any dovishness lights a fire under gold mining stocks even more than it does bonds. In fact, given their respective volatilities, a portfolio can perhaps be protected against a dovish Fed by holding gold miner stocks at just a quarter the level of long dated bonds.

The third risk is that growth implodes and equity markets re-adjust to a much lower structural growth environment in which the myth of the Fed as “price keeper” of last resort is finally put to rest. However, as Wednesday’s markets showed, we seem to be far from such a realization. Instead, the belief remains that of an omnipotent US central bank.

This isn’t to say that the somewhat unnatural correlation between long-dated treasuries and gold miners is some new permanent feature. However, so long as the Fed leans on the dovish side, and equity investors assume that the central bank is fighting their corner, the correlation between these two assets will likely remain. And from a portfolio construction perspective, this means that investors can hedge a dovish Fed with a modest amount of capital tied up in gold miners, as opposed to a pile of long-dated treasuries, or even puts on the US dollar.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.