"Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference."

-ROBERT FROST

Those who track financial news might have seen that Eugene Fama and Robert Shiller were recently awarded the Nobel Prize in economics. Fama is considered one of the founding fathers of the efficient market theory (EMT). Essentially, he concluded that the price reflected by the markets at any given time is so accurate and so instantaneous that any attempt to "outthink" it is a waste of time and money.

Robert Shiller comes from a starkly different background and believes in the power of behavioral economics. He has become one of the leading thinkers on how emotion impacts economic decision-making. Aside from their similar prestigious academic pedigree, calling them the odd couple is putting it lightly. In fact, the idea of them collaborating on the Noble Prize is about as far-fetched as John Boehner and Barack Obama penning a book titled The Art of Win-Win Negotiating. The concept that recently earned Shiller and Fama’s Nobel Prize is best summarized by the Washington Post as follows:

"We know that stock prices behave randomly on short-term horizons, and that efforts to time the market in the short run are probably counterproductive. But we also know that markets can become broadly mispriced for long periods due to the mysteries of human psychology."

Said in more basic language, in "normal times" the markets are fairly efficient at telling us what certain assets are worth. At extremes, however, the information (or prices) being reflected by the market are so influenced by human psychology (greed or fear) that valuations do not reflect the true worth of an asset. This is a very significant breakthrough, as it concludes that markets are perfectly rational, except when they are not. Obviously, this is less than reassuring.

The announcement of their award is timely as this week’s EVA is focused on the effects of emotion on human decision-making, specifically, an examination of how investor thinking is altered by certain cognitive predispositions. Many have and will continue to discount its role in economic decision-making and investing. I hope that after reading this you will have settled on a very different conclusion.

An unarguable fact, only debated in its severity, is that the average investor has perfected the practice of mis-timing markets and, as a result, earning returns far below what they should realize. Our intelligence as individuals has little correlation to our success as investors because it’s not always our intellect that drives investment decisions. Intellect becomes obscured as our own mind wrestles between psychological biases and basic logic. Investors who operate unaware of this relatively obscure field of finance stand almost no chance of outperforming those who understand these psychological limitations over any meaningful period of time. If we understand these biases, we can formulate processes, structures, and methods that allow us to avoid such mistakes. Otherwise, in my opinion, it’s analogous to playing poker against someone who can see your cards.

This isn’t a theoretical exercise that hypothesizes on some abstract analysis of human psychology. It’s real and has tangible impacts on those who make superior gain in the financial markets and those who underperform long-term or even lose money. Investors who can’t identify and control their blind spots are signing up for a wealth transfer from their investment accounts to those who understand these concepts.

OVERCONFIDENCE

This bias probably doesn’t apply to you, right? You just confirmed one of 93 readily listed biases regarding the way we think about financial decisions: Overconfidence! Don’t believe it? Please take a short quiz.

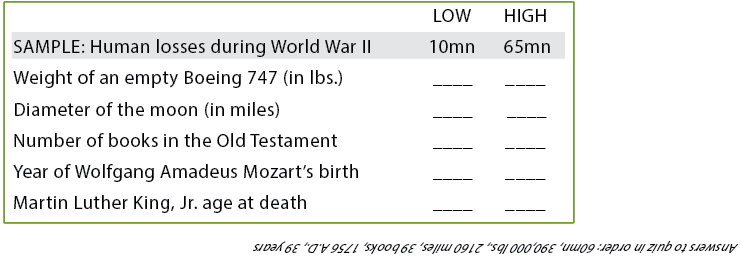

On the next page is a brain exercise that I have borrowed from a book called The Little Book of Behavioral Investing (well worth the short read). It lists a handful of questions and asks you to create a range that you are 90% confident will surround the answer to the corresponding question. For example, if I asked you how many lives were lost during World War II, you would make a low guess and a high guess that creates a range that you are quite sure (90% sure) captures the correct answer.

If the correct answer falls within your range, then you got it right. Now, try to answer the questions following the directions just given.

How many did you get right? The average person gets only 1 or 2 correct, which isn't what you would expect since you were asked to be almost certain of your answer. One would infer that the average correct score given a 90% confidence range would be 4.5/5.

We as humans overestimate our abilities. Studies confirm this as they highlight how much we think of ourselves relative to others. A survey found that 93% of American drivers believe they are above average. My personal favorite is when asked how likely the following people were to be/get in heaven, the results were as follows: Princess Diana, 60% ... Michael Jordan, 65% ... Oprah Winfrey, 66% ... Mother Teresa, 79% ... Themselves, 87%!

It seems to go without saying that overconfidence in any aspect of life is dangerous. An overconfident skier takes on parts of the mountain that can cause physical harm. An overconfident driver ends up careening around a slippery bend in the road. Overconfident investors find themselves pursuing strategies they don't understand with people they shouldn't trust. We see this all too often. On a national level, this was really the heart of the Madoff scandal. He promised too-good-to-be-true returns, but his Ponzi scheme was fueled by overconfidence and attracted lots of investors, including some who were quite "sophisticated." Locally, our firm was fortunate to have avoided what many others did not when Darren Berg of Meridian Group swindled almost %150 million from investors in the Pacific Northwest.

MISREMEMBERING

I've noticed an interesting trend when it comes to people who've returned from Las Vegas: They never lose money. I began keeping track over the past year, and roughly 75% of people tell me they at least broke even. It's amazing how that place stays in business. Even more startling is the number of investors who "misremember" performance of their accounts.

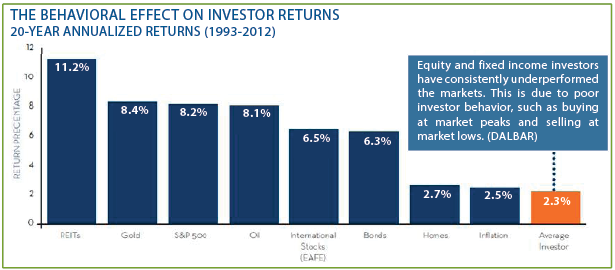

It’s hard to look at the chart above and conclude something besides that many investors struggle to produce even mediocre returns. Another recent study found that investors, on average, overestimated their investment returns by 11.5% annually. That is not a typo! In the field of behavioral finance, this is called cognitive dissonance. Are investors oblivious or in denial? I think the answer is: It depends. Our memory can work as a defense mechanism. If the truth is too painful, our brains just change the way we remember things. Going back to the beginning of human existence, this is a very powerful tool that helps us process and move on from very traumatic events. Within the investment world, though, it’s a rather perilous practice.

In many ways the investment world is all too happy to help investors ignore or misremember past performance. After all, who wants to be told their accounts are underperforming? It’s actually quite striking to me how many investors’ statements come without a benchmark attached to them. Evergreen, on our own volition, adheres to set performance standards, known as Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS), which require us to put a benchmark on all client statements we issue. For obvious reasons, some registered investment advisors avoid showing comparative benchmarks at all costs. Let me make a final comment on tracking your performance: Make sure you are using a benchmark that is representative of the securities held in your account. Many investors compare themselves to the stock market despite having a very different composition of securities than the stock market. That’s comparing apples to oranges.

HERD BEHAVIOR

In Homer’s iconic poem, The Odyssey, Ulysses is warned that during his voyage from Troy he and his crew will encounter beautiful Sirens, when, with enchanting songs, they will tempt his men into a watery grave. In anticipation of such temptation, Ulysses stuffs his men’s ears with wax and binds himself to the ship’s mast. You may be wondering what one of the world’s most celebrated pieces of historical literature has to do with the principle tenants of investing? We all feel temptation, just as those sailors and Ulysses were certain to face during their journey. As investors, we are always lured by the idea that we should somehow be doing better. Imaging of the brain has detected the emotion triggered when we are informed that another person earned a higher rate of return. Jealousy? No. Envy? Nope. Pain: The same part of the brain that activates when we break a bone lights up when we see others doing better than we are in the markets. Well, who likes pain? No one. The knee-jerk reaction to stop the pain often leads investors to "join the party," often at an extremely dangerous time.

Two curious observations of human nature show how our desire to follow the crowd supersedes logic. In one experiment, the observers trigger an emergency in a room crowded with people. Two emergency exits are equidistant from the crowd. Once alerted to the threat, you might surmise that everyone would simply run to the nearest exit. That didn’t happen. Instead, the vast majority of people tried to crowd through one exit. When picking a restaurant, following the crowd might be a good practice. When picking an exit in a crisis, following the crowd is dangerous. And most relevant, when picking investments, following the crowd can be very costly to your nest egg.

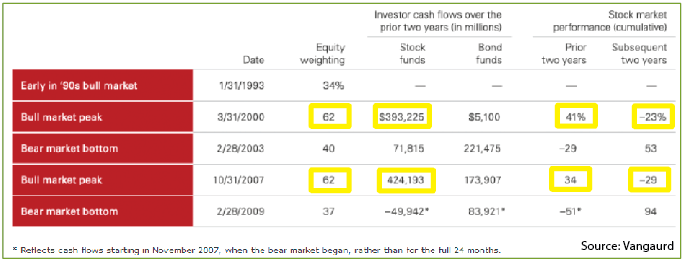

Here’s a real-life example of exactly how costly it has been to be a me-too investor. There were 2 years over the last 15 when investors maximized their exposure to stocks. Don’t look at the chart below yet; instead, try to recall the two most destructive market declines we have seen over the 15 years.

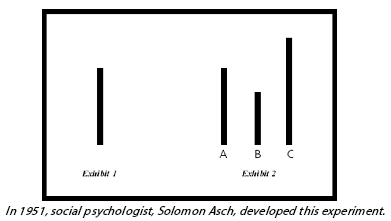

You got it—investors maximized their exposure to stocks (relative to bonds) in 2000 and 2007, perfectly imperfect. But it’s not because we are stupid. The way we are wired "defaults" us to behave this way. The influence of others can play tricks on the otherwise unbelievably efficient human mind. In this case, I borrow from GMO’s James Montier’s wonderful book, Behavioral Finance: Insights into Irrational Minds and Markets, which is worth reading if you have the time. In it, he recounts an elementary exercise in which people are asked to identify which line from exhibit 2 matches the line from exhibit 1. See on the next page:

Line A obviously matches the length seen in exhibit 1. I got this right, after staring at it for about five minutes, and I was quite proud of myself. Then reality set in. It’s supposed to be easy. Would you change your mind on something so very basic if you watched 10 people pick the wrong choice before you answered? Of course we wouldn’t because it’s so obvious. But guess what? Remarkably, the study’s creator found that 30% more people missed this question when they followed 10 incorrect guesses. Logically, we know what’s right, but as more and more people begin to tell us something different our brain starts to doubt itself. Do you think this doesn’t happen in investing, when we are inundated by seemingly infinite amounts of conflicting data from experts who seem so sure that you wonder if they have ever been wrong?

If we can agree that our instincts can lead us down very dangerous paths, how can we find the right path? Who cares about paths? How can we find the right investments? These are serious questions with a simple but unorthodox answer. If I asked you to choose between the two investments listed below, which would you select?

Fund A Past-Year Return 15%

Fund B Past-Year Return -10%

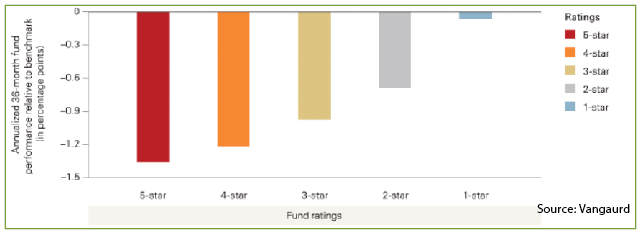

Intuitively, we all say Fund A. But the following chart suggests something much different. Five-star-rated funds tend to be those with the best track record in recent years, but, as is clear from this chart, past performance truly is no guarantee of future results! Unless, that is, you analyze it counterintuitively.

In 2005, Bill Miller was widely regarded as the greatest portfolio manager on the planet. He was a god on Wall Street. His fund, the Legg Mason Value Trust, had beaten the S&P 500 for a record 15 consecutive years. He was the face of Legg Mason and, at his peak, he managed almost $22 billion of client assets. But 2008 struck and it hit Miller particularly hard. He held Eastman Kodak and Bear Stearns. His legendary fund fell 58% and investors yanked assets at a fevered pitch. He lost $10 billion in a short period of time. Today, his fund manages around $2.5 billion. He hasn’t beaten the S&P 500 once since 2005, though he is on pace to do so in 2013.

Miller represents a rather high profile fall from grace. But Miller isn’t alone in underperforming the markets. Let me be very clear because I think this is one of the most misunderstood concepts made by investors who hire an investment manager: Even the very best investment managers in the world underperform at times. To be specific, an analysis of the top-rated mutual fund managers found that at some point nearly 60% of them lagged their benchmark by 10%. If the best lag by 10%, even good managers can go through a period when they also struggle to keep pace.

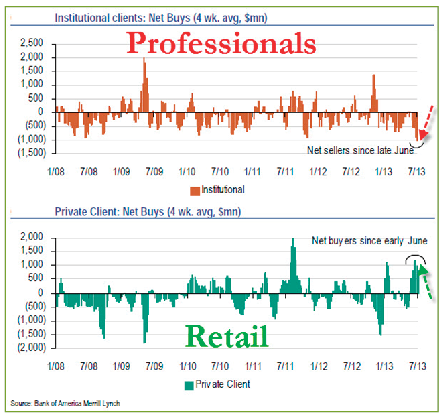

Many of our clients have been through a full market cycle. They can remember back to the days of the real estate bubble, a time when we were told that real estate never went down. We were assured that the new methods for packaging mortgages made the system less risky. It was a time when the term "flipping houses" went from a speculative gamble to a respectable career. And, we were told this time will be different, the famous last words of investing. Then, poof—in what seemed like an instant, stocks were down 60% from peak to trough. Home prices were slashed. Foreclosed homes became free housing for squatting tenants. Fear took over the financial markets, and investors couldn’t find enough safe securities, such as bonds, to put into their portfolios. Bonds represent safety in bear markets, but in bull markets they are viewed as dead weight. It seems that these days they are believed to be closer to the latter than the former. Equities are all the rage, especially for the retail investor. What normally happens next? I’ll let form your own conclusions after reviewing the chart below.

If you’ve made it this far, you’re probably wondering one of two things. First, why am I still reading? Second, how can I use behavioral finance to improve how I invest?

The purpose of this week’s EVA is not to communicate a sense of hopeless struggle against our innate inner urges. Instead, the goal is to create an awareness and methodology for dealing with the emotional struggle that faces every type of investor. Just like in the game of golf, there is no single tip that can apply universally to improve all swings. The same is true here. Without being privy to each reader’s specific background, it’s impossible to determine a strategy for combatting our preprogrammed biases. I can, however, outline the steps our firm has taken to not only limit the impact of our cognitive predispositions, but also to put our clients in a position to benefit from the missteps of others.

About eight years ago, we trademarked a process that tracks the movements of the general investing population. What we found, unsurprisingly, is that investors would shift the allocation of their assets based on performance. Using mathematics (far beyond my pay grade) we can quantitatively measure when the assets flowing into or out of a specific area of the market hit, for lack of a better term, hysteria levels. We then use some basic valuation tools to confirm the excess fear or greed.

This methodology allows us to do two extremely useful things. First, it allows us to see bubbles forming in a concrete context. (The word "bubble" flies around all the time, but we are actually tracking the money that creates bubbles.) Second, our process leads to clear tactical buy and sell decisions. This may seem unimportant, but having a discipline set up in advance that helps you make buy and sell decisions is critical for sound investing. Sir John Templeton used to have standing instructions with traders on the floor of the exchange to buy during significant market declines. They were standing orders because he knew that the overwhelming emotions at that moment could override what he knew to be an intelligent dollar-cost-averaging strategy.

The reality is that most investors don’t have a strategy to deal with the psychological rollercoaster that comes with investing. If you don’t create a plan to deal with our congenital investment defects, you’re not investing—you’re speculating. Why speculate from behind a desk staring at a computer when there is a city in Nevada that can make losing money so much more fun? At least they’ll buy you a drink while they take your money.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. All of the recommendations and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Information contained in this report has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Evergreen Capital Management LLC makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, except with respect to the Disclosure Section of the report. Any opinions expressed herein reflect our judgment as of the date of the materials and are subject to change without notice. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their financial situations and investment objectives.