“No thief, however skillful, can rob one of knowledge, and that is why knowledge is the best and safest treasure to acquire.”

– L. Frank Baum, “The Lost Princess of Oz”

“Knowledge, like air, is vital to life. Like air, no one should be denied it.”

– Alan Moore, “V for Vendetta”

“An investment in knowledge always pays the best interest.”

– Benjamin Franklin, “The Way to Wealth: Ben Franklin on Money and Success”

Introduction

Regular readers of this newsletter are likely aware of our enthusiasm for quotes. Every newsletter we publish starts off with a relevant saying from a favorite author, politician, economist, historical figure, celebrity or businessperson. In fact, to quote a quote about quotes from the legendary actress Marlene Dietrich, “[We] love quotations because it is a joy to find thoughts one might have, beautifully expressed with much authority by someone recognized wiser than oneself.”

Depending on the subject matter of a particular newsletter, it can either be quite easy or unexpectedly arduous to find the perfect summation of an extensive and often multi-layered rumination. In the case of this week’s missive, the job of identifying several quotations for a theme about “knowledge” was “as easy as pie” (to quote a popular colloquialism derived from the 1855 book “Which: Right or Left?”)

The reason this week’s task was so simple is because human’s fascination with access to knowledge is as old as the earliest accounts of humankind in the Bible. The first Old Testament story in the Garden of Eden describes how eating from the tree of knowledge of good and evil was forbidden and presented severe consequences. (And most of us know how that story played out…)

With instant access to the internet and information today, the knowledge revolution currently underway also has numerous potential consequences for the established order. As Louis Gave points out, the shifting power dynamic between people and information is a key catalyst for many of the upheavals around the world, with potentially harsh ramifications for governments and economies.

In the midst of this growing instability, and in order to protect against some of the trends Louis describes below, we have suggested that increasing exposure to hard assets is crucial. History shows that when central banks print money and use that to purchase their government’s debt (as the Fed is doing once again, a process known as debt monetizing), it creates a temporary boom, but the payback is often painful. It seems unlikely that today’s problems will be resolved by continuing to throw money at them – despite—or, perhaps, because of--central banks best efforts. Those with exposure to hard assets (such as precious metals, real estate, farmland, and oil) have typically been at least somewhat insulated from the fall-out caused by money printing and monetizing sovereign debt in the past. We expect the same to be true as the knowledge revolution expands and more pressure is applied to the status quo.

The Knowledge Revolution and Its Consequences

It is said there are “no atheists in foxholes”. When things get desperate, we all like to imagine a better outcome on the other side of whatever nightmare is being endured. It is also the case that when facing challenges, a natural reflex is to cling to beliefs installed in us at a young age. This brings me to a “go-to” line I often use when giving a speech; namely, that I was raised in the French educational system and while you can take the “boy out of France”, you can’t take “Marx out of the boy”. And given the past year’s riots in Paris, Hong Kong, Cairo, Beirut, Barcelona, Santiago and other cities around the world, it is hard to avoid falling back on the Marxist catechism of my youth. Of course, on the surface, the riots currently sweeping the globe seem to have very different causes. Specifically:

In short, like the families in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, it looks as if citizens in almost every country are unhappy, but unhappy in their own special way. Yet, confronting the images on the nightly news of riot police with batons drawn in the world’s various major cities, it is hard to shake off Karl Marx’s observation that the economic infrastructure determines the political superstructure.

Economic infrastructure vs political superstructure

Back in 1867 (when he published Das Kapital), Marx foresaw that the pyramidal models necessary to run large companies with many foot soldiers would be the root of powerful nation states in the 19th and 20th century. At a time of industrialization, states began to be organized along centralized and hierarchical lines. Marx correctly analyzed that the wave of revolutions that swept across Europe in 1848 was a direct result of tensions between an economic infrastructure which had become driven by industry, and a political superstructure that remained dominated by agricultural interests.

Marx’s conclusion, however, turned out to be wrong. He predicted that the conflict between the agrarian political superstructure and industrial economic infrastructure would spur revolutions which, in turn, would secure the “dictatorship of the proletariat”. Instead the successful countries evolved from being censitary democracies (usually based on land owning) to the full-on representative democracies and welfare states we know today. This brings me to a recurrent theme of our research, namely, that our modern Western economies have become knowledge-based.

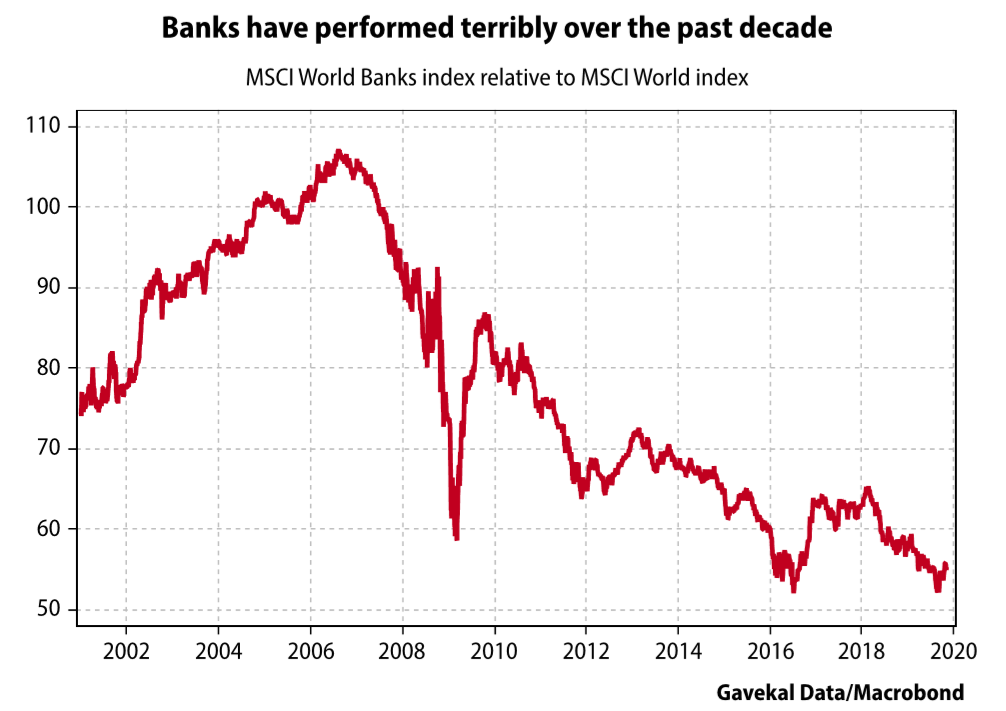

Thus, to the three factors of production used by Marx (land, labor, capital) a fourth must be added: knowledge. This has proven to be a game changer. And at the risk of dislocating my (three times broken) shoulder as I pat myself on the back, I would highlight that the key themes in both my 2005 book Our Brave New World and my 2012 book Too Different For Comfort is that the world (outside of emerging markets) no longer belongs to those who can mobilize land, labor, or capital; but to those who have “knowledge”. Simply put, having two strong arms and a willingness to work has, for the past 15 years or so, no longer been a sufficient condition for economic success. Neither is having access to capital (witness the terrible performance of banks all around the world over the past decade). Instead, power now resides among those best able to organize knowledge. And in itself, this creates a new challenge, as knowledge now spreads much faster than ever before.

Knowledge and revolutions

To some extent, the first genuine European revolution was launched in 1517, when Martin Luther nailed his attack on the political powers of Rome to the door of Wittenberg Castle Church. This act unleashed a century of religious wars, millions of deaths and dramatic changes in Europe’s political landscape. Interestingly, however, there was little “new” per se in Luther’s theology. Some of his points made had been embraced previously by the Cathars of South West France, St Francis of Assisi, Erasmus, Jan Hus and John Wycliffe. Yet, it was Luther’s words that traveled far and wide. And this for a simple reason: a generation before Luther, Gutenberg had invented the printing press. All of a sudden, knowledge was no longer confined to monasteries, but instead made available to a broader public. Fast forward a few centuries and the revolutions of 1848 coincided with the laying of railroads across Europe, and thus the enhanced ability of ideas and information to travel. But then railroads also happened to make representative democracy possible. All of a sudden, people living in Cardiff, Dundee, Liverpool or Newcastle could choose a local doctor, a respected lawyer, or (in time) a trusted trade unionist to go down to London and (i) represent their interest, and (ii) report back on news from the capital city. Which brings me to today and the direct consequence of the knowledge revolution. Almost everywhere you look, the population seems to hold the following beliefs:

In short, representative democracy was a system built on the back of a “top-down” economic infrastructure in which—given the travel distances between say Toulouse and Paris, or Paris and Clermont-Ferrand—it made sense for communities to be “represented” in Paris (or London, or Washington DC, or Ottawa). This was doubly true given that information hardly flowed freely and the good people of Toulouse, or Toulon, were often in the dark about important changes unfolding in the capital, or elsewhere across the land.

But the world has now changed.

Today, knowledge, and information, are more diffuse than ever. This new reality should point towards new political arrangements.

One of the most obvious consequences of the internet has been to cut out the need for middlemen across most industries, or at the very least, to force middlemen to justify their existence. Why should politics be any different? After all, what are politicians if not the middlemen (and women) between a population and a required political outcome?

The knowledge revolution should spark a shift towards direct democracy. Yet the beneficiaries of representative democracy are fighting this transition as it threatens their livelihoods and their social status. This much has been clear through the whole Brexit debacle; an episode through which the people’s representative body fought hard to cancel a decision taken by the people as a whole. As a result, proponents of representative democracy had to twist themselves into ever more pretzel-like formations. Their argument was that people should be trusted to elect representatives, but not trusted enough to make direct decisions, as it could devolve into mob rule. This condescending stance is increasingly challenged by the fact that:

In short, the knowledge revolution has dramatically changed the economic infrastructure, but our political superstructure has barely evolved. This is problematic and the logical political progression should be for direct democracy to take over from representative democracy. Meanwhile, the proponents of representative democracy increasingly find themselves in the uncomfortable position of the British aristocracy at the time of the Corn Laws, defending abhorrent privileges for themselves. Ironically, Marx would not be surprised by this turn of events: the “representative democrats” having conquered the State, have become the system’s most conservative force.

Different political responses to the knowledge revolution

For the latter day aristocrats, one possible way to deal with a loss of status and income is to make the political system more complicated than it need be, and so justify one’s own existence. This is what we have seen in Europe for the past 20 years. Instead of moving towards more decentralization and more dilution of power to lower, more local, levels, policymakers have attempted to construct a European empire that is so complicated that direct democracy within the broader political construct is impossible.

Thus, as the clash between economic infrastructure and political superstructure creates political tensions, it seems likely that smaller political entities (like Singapore, Switzerland, Iceland and New Zealand) will find the necessary evolution towards direct democracy easier to achieve than big, imperial political constructs like the US, China, Russia, or the EU. Such small countries are more likely to offer political stability to investors; a situation which, in this age of revolution may start trading at a premium.

One reason that assets based in countries able to evolve gradually towards more direct democracy should start trading at a premium is that the first way for leaders of big empires to “protect” living standards will be to offer the signature of the captured state and borrow to finance an unsustainable lifestyle. This is what French Kings always did: borrow heavily to prevent any rebellion among the nobility (alas, for Louis XVI it was not the nobles that revolted, but the people). Today, the contradiction between the economic infrastructure and political superstructure means that to keep political peace governments must (i) spend lots of money or (ii) take control of the flow of information. And clearly, these are the two big political trends that are now moving forward at an exponential pace:

With this, it is possible to see countries embracing one of three different paths.

As things stand, there are few countries in the first category. The obvious example is Switzerland (which perhaps explains why the Swiss franc has remained one of the world’s strongest currencies. It is possible that countries with Queen Elizabeth II on the banknote (UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) will head in that direction. The common law system is adaptable and British-style parliamentary democracy has proven resilient to shocks, while displaying an ability to evolve with the times, and without the need for costly revolutions.

In the second category sit other Western democracies, namely, the US (where government debt is surging) and most EU countries. The worry, however, is that these morph into third-category countries, where elected representatives spend money they do not have to justify their existence and also seek to control the diffusion of information.

An interesting side question is whether the rise of crypto-currencies reflects a market response to governing elites’ effort to keep their privileges by capturing society’s common goods. After all, is there a more “common good” than a country’s currency? And aren’t the attempted debasement efforts we have seen a visible effort by governing elites to maintain their status and income? As such, the rise of crypto-currencies may be the biggest threat to today’s welfare states and political arrangements. If governments lose control of their currencies, the clash between economic infrastructure and political superstructure may devolve into outright revolutions. Could this explain why a (fundamentally Marxist) Xi Jinping is now pushing for the adoption of crypto-currencies? In his Marxist reading of the world, does Xi see the loss in confidence in Western currencies as the coup de grace for their welfare states, which will allow China to be the world’s economic superpower by the time of the People’s Republic’s 100th anniversary?

Conclusion

In A Study of History, Arnold Toynbee argued that the role of a society’s elite is to rise to the challenge of the times, and find solutions fitting to those times, even if this involves a radical break with the past. Yet the modus operandi for most leaders is to try and maintain the status quo, and restore the “old order” that prevailed before the disruption. But if the problems are large enough, this does not work, and the same challenges reappear until either a solution is found (e.g. the EU project as the solution to the Franco-German rivalry), the elite is replaced by a new elite (i.e. revolution), or the country, system or civilization disappears (e.g., the end of the Soviet Union).

If one buys into Toynbee’s grid of reference, and into Marx’s dialectic on clashing economic infrastructure and political superstructure, it seems unlikely that current tensions will be resolved by throwing money at them. As such, today’s global street riots show there are limits to the ability to buy votes. Yet even if throwing money at problems won’t work, it doesn’t mean this won’t be the solution adopted for years to come. Such a response should lead stewards of capital to deploy their wealth in the countries with perceived stronger, and more flexible, political institutions. Today, for me, those are Switzerland, Singapore and the countries of common law.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.