“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.”

– Milton Friedman

“Do I think we will continue to see wage inflation running at 7% year-over-year? Not really…But I can tell you that month-over-month wage increases THIS spring are running at more than 10% annualized.”

– Ben Hunt, author of the highly regarded financial newsletter, Epsilon Theory

“When the people find that they can vote themselves money that will herald the end of the republic.”

– Benjamin Franklin

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Summary

To Be, Or Not To Be, Transitory

Well, that was quick! Back on October 30th of last year, which also happened to be my 65th birthday, we put out a typically against-the-grain EVA on a topic that was very much back page news at the time: inflation. Fast forward to last week and here is the cover of that edition of Barron’s.

In our EVA of nearly seven months ago, I made the case that inflation was poised to accelerate as we moved into 2021, particularly once vaccines became broadly available. For sure, I got lucky in one huge regard: mere days after our October 30th, 2020 EVA, Pfizer’s “vax” breakthrough news hit. Yet, even prior to this event I was convinced 2021 would bring copious amounts of positive Covid and economic news, a view that wasn’t widely accepted at the time.

The investment implication of this outlook was to overweight securities that would benefit from re-opening, reflation and, before too long, the less desirable “flation”, the one that starts with “in”. As regular EVA readers know, often when I make these forecasts, I’m early…sometimes, way, way, too early. But, in this case, my timing was pretty much spot-on (thank you, Pfizer!).

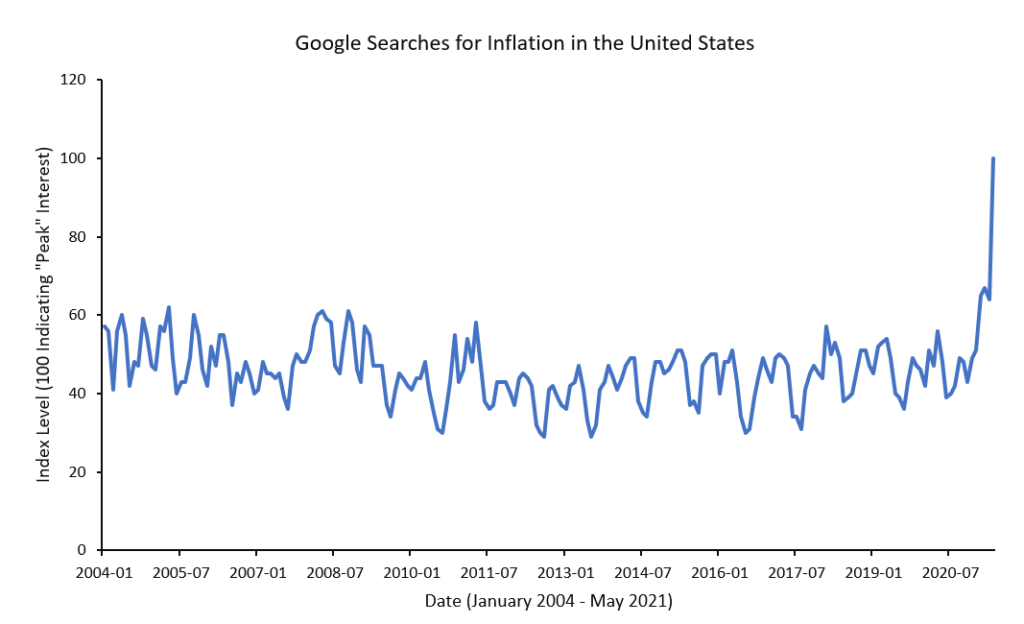

As many of you are also aware, whenever something makes the cover of a major periodical the congenital contrarian in me believes a reversal is near at hand. In my experience, Barron’s is much less of a cover story kiss of death than, say, The Economist or Business Week, but, nonetheless it makes me uncomfortable. The same can be said of this graphic:

Source: Google, Evergreen Gavekal

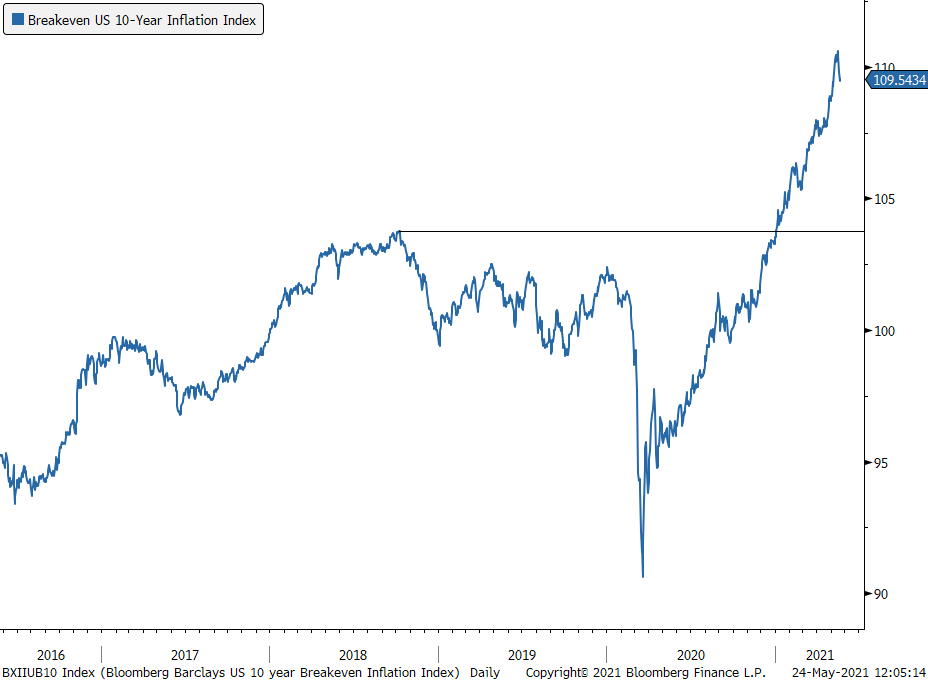

Another core belief of mine that I hope EVA readers have assimilated is that it nearly always pays to go-with-the-flow when it comes to multi-year breakouts. Usually, in this regard, I’m referring to stocks, sectors, foreign markets or primary investment styles (such as Large Cap Growth) but it also applies to commodities and, a bit less conventionally, inflation expectations. Per the below images, both commodities and the bond market’s anticipation of inflation over the next decade have had major breakouts. (The horizontal lines mark the critical three-year resistance levels that have been exceeded-- in both cases way, way, exceeded, which is why I’m near-term cautious.)

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

So, to be clear I believe we are seeing broad and powerful confirmation that we are in a new long-term (aka, secular) bull market for hard assets like copper, gold, silver, palladium and energy. This is an investment theme I’ve been harping on even before Covid crushed the prices of all of these; however, thanks to the Fed’s fabricated trillions, the pandemic ironically launched them into the ionosphere…and beyond. As you can see, the outperformance of the left-for-dead energy sector versus the long-exalted tech sector since that October 30th EVA has been stunning.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

If you sense a “however” coming you get a gold star (or maybe a palladium star is better yet these days). Even in mega-trending bull markets, pull-backs, corrections, adjustments, retracements, whatever you want to call them can be brutal. Often, these flush out the trend-following tourists (see the recent bloodbath in the cryptos).

If you were carefully reading EVAs last summer, as our beloved precious metals (PMs) holdings were going vertical, you noticed that we suggested profit-taking. Much more importantly, we were doing that in actual client portfolios. In most cases, our positions in the PMs, and the miners thereof, had risen above our target weight. Consequently, we methodically took profits (I know, there’s that incendiary phrase of mine again) and reduced our holdings back down. This is despite the fact that we remained bullish on the long-term uptrend.

Then, starting last fall and through the winter, as gold, silver, and the miners corrected (with the latter, as usual, taking much more of a beating than the metals; the main gold miner ETF tumbled by 33% from its summer peak), allowing us to dollar-cost-average on weakness back into them. The gold miner ETF has risen by a third from its March 1st low, a most pleasing development. (Interestingly, this has occurred even as gold’s new digital rivals—the cryptos—have been crushed.)

In fairness, some commodities have had much more spectacular increases than gold, and even the inherently much more volatile silver. Lumber, for example, rose by 457% since March of last year, versus gold up “only” 27% and silver roughly 100%.

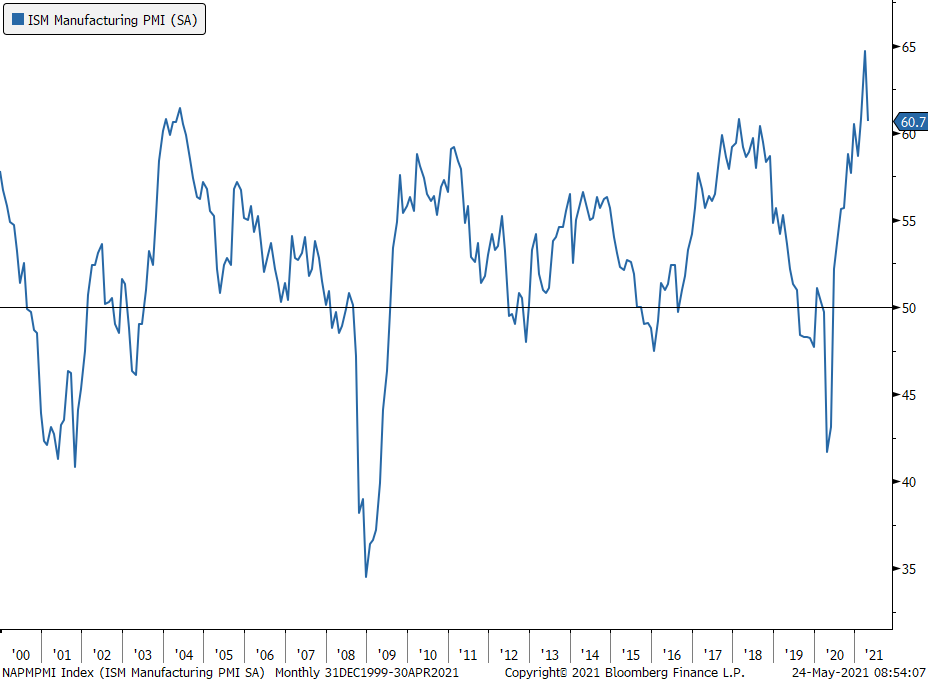

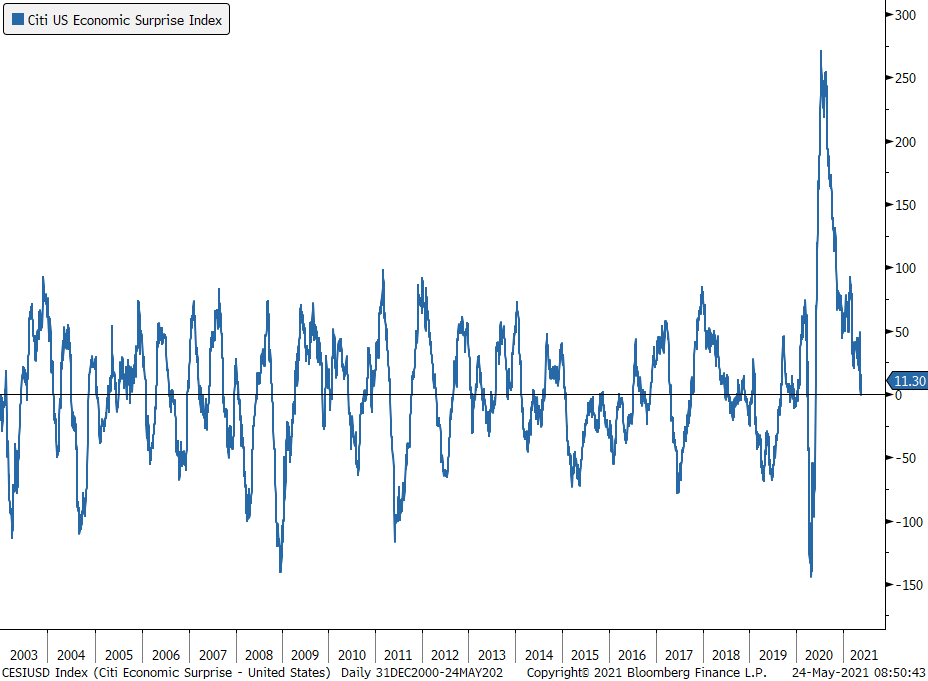

When it comes to financial markets and, especially, commodities, the trend is your friend, at least on a short-term basis. Thus, it can be hazardous to say what I’m about to: That it might make sense to cut back a bit on your hard asset exposure, similar to what we did with miners last year. In my opinion, the more cyclically-oriented commodities, and related equities, are more vulnerable than gold which, as noted, has already had its spanking. One reason for my view is that there’s a good chance we’re going through a peak growth expectations and, related to that, peak inflation fears phase right now. Economic datapoints like the critically important Purchasing Managers’ Index are at levels where a sharp downward move is highly likely. The Citigroup Economic Surprise Index is already telegraphing (there’s a quaint word) a reversal.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

You may have seen that the April CPI number came out much hotter than expected, catching the see-no-inflation Fed off guard. Additionally, even prior to that shocker, the CPI was rising at a 5% annualized rate. As a result, career disinflationists like David Rosenberg and Lacy Hunt have been on their heels lately as the data has been running hard against them.

Some of you are aware that I was asked to speak two weeks ago at John Mauldin’s Strategic Investment Conference (SIC). In full disclosure, the only reason I received an invite was a last-minute cancellation by another speaker. The lone previous time I was given the podium at the SIC was in 2016 when I made the reckless prediction that the Fed would buy corporate bonds during the next crisis. Admittedly, it took four years and a global pandemic for that to occur. Perhaps that’s why I hadn’t been invited back since then (just kidding, John).

During my brief comments, I admitted to the 4,000 or so virtual attendees that I was a defector. After forty years as a deflationist and bond bull, I conceded that I’ve switched allegiances and am now firmly in the inflationist camp. Frankly, I feel like a traitor to my cause but, as John Maynard Keynes once said, “When the facts change, so does my mind. What do you do, sir?”

As anyone regularly reading my EVAs over the last two years recognizes, this has been an evolutionary process. But as recently as going into Covid, I was still a bull on high-grade bonds. It was the US government’s fiscal and monetary responses to the virus crisis that turned me. In essence, it was the implementation of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) that did the turning.

Back in April 2019, I first introduced MMT to EVA readers when it was just a wild theoretical idea, primarily championed by Stephanie Kelton, the former economic adviser to Bernie Sanders. Now, however, Professor Kelton is advising the Biden administration and de facto MMT is being embraced by both the Fed and the US Treasury, currently led by Janet Yellen. It’s becoming inarguable that MMT has gone mainstream, with the majority of Americans reportedly in favor of the trillions of freebies being spewed out at a flow rate akin to the Mississippi River at flood stage. Even one of my fellow panelists (a famous Wall Street strategist) on the SIC opined that perhaps MMT is a reasonable approach given current conditions.

Others, like Rosenberg and Hunt, believe that MMT will lead to falling inflation and further economic stagnation. They note that past government spending sprees have created those outcomes. However, I vehemently disagree with both the view that MMT is benign and appropriate, as well as that it will have the same ineffective economy-boosting result it had under both the Obama and Trump administrations. Each of those included the Fed’s various QEs (a milder form of MMT).

One huge difference now versus under Obama and Trump is that the bond market is largely being bypassed as a deficit funding source and, of course, the numbers are almost unfathomably large. Under Barack Obama, in particular, deficit spending largely flat-lined after the initial Great Recession explosion. (Donald Trump’s policies did lead to an indefensible doubling of the deficit to 5% of GDP, or $1 trillion, even during a healthy economy; this set the stage for the freezing up of the overnight bank lending market—aka, the repo market—which forced the Fed to effectively initiate its fourth round of quantitative easing.)

Of course, today we’re talking trillions upon trillions of deficit spending, about $5 1/2 trillion since the September 2019, “Repo Madness” event. The Fed’s balance sheet has increased by about $4 trillion since then; the Fed expands its balance sheet by fabricating funds from its Magical Money Machine (MMM), using those to buy government bonds. To quote the Wall Street Journal on this topic, from a May 13th Op-Ed, “The Fed has monetized nearly all of the new federal debt issuance of the year, and Democrats are counting on the Fed to keep it up in the years ahead.” Based on the Fed’s current modus operandi, I don’t think the Democratic party will be disappointed in the least. While the Fed did some debt monetization during the early QEs, it was to a much lesser degree, with real-money bond buyers relied upon to a far greater extent. It also sought to roll back QEs during 2017 and 2018, an almost incomprehensible move these days, as I will discuss shortly.

Over the last twelve years of increasingly radical government monetary (the Fed) and fiscal (the Treasury) policies, we’ve all become numb to the extreme nature of their actions. But, good reader, debt monetization is what developing countries resort to when they are in serious trouble. Surging inflation and a collapsing currency are the inevitable results.

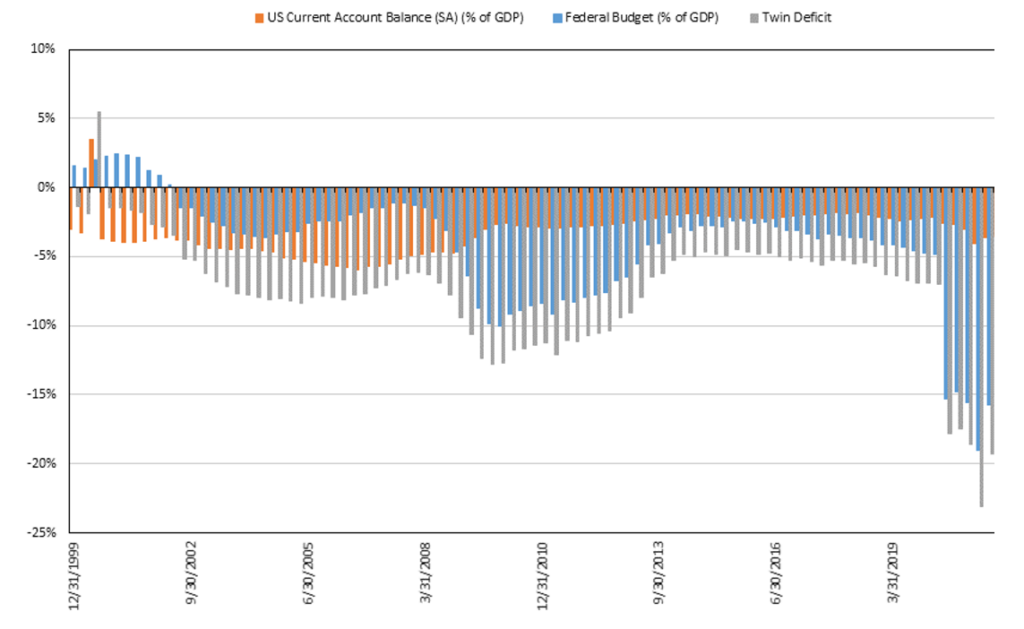

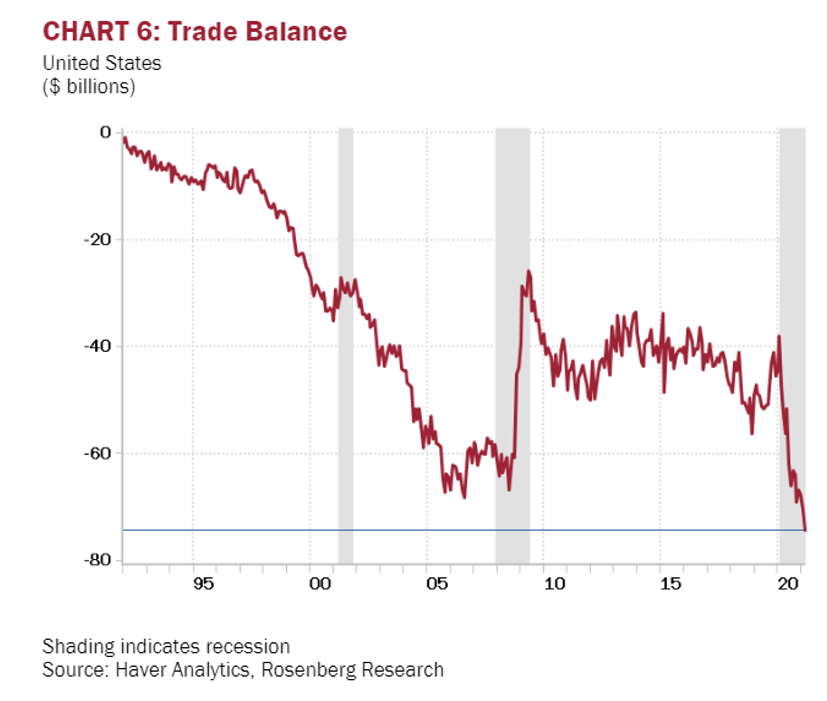

It’s natural to think that can’t happen in the US given our enormous wealth and reserve currency status. But I’m not so sure. As I’ve written many times in the past—and stated at the SIC—prior MMT policies in other countries (and they have been attempted many times but without the fancy name) consistently have led to currency and inflation crises. Japan is often cited as the exception to this rule. However, there are tremendous differences between the US and Japan. To name just two of the most significant, Japan runs a massive trade surplus while the US runs an equally massive trade deficit. Ominously, the US trade deficit just broke down to a new low, implying that trend has further to run.

Source: Bloomberg, Evergreen Gavekal

The other striking divergence is that Japan is one of the world’s biggest creditor countries. In other words, it owns far more in overseas assets than it owes the world in foreign-held debt (Japan’s monstrous amount of government debt is owed almost entirely to its citizens, banks, and other domestic corporations). Conversely, the US is now a debtor country to the tune of about 64% of GDP (around $13.9 trillion).

Besides believing that multi-trillion deficits are actually growth- and inflation-retarding, my disinflationist ex-soulmates list a number of other reasons for expecting inflation to stay around 2%, if not lower. Among them are: an aging US population (old folks spend less); technology breakthroughs, such as robotics and artificial intelligence (potentially leading to a productivity boom); depressed money velocity (which neutralizes the trillions the Fed has created out of its MMM) and a drastic reduction in healthcare costs (again, due to technology advancements).

These are all valid points and I do think they will serve to moderate the inflationary up-cycle I see in the years ahead. But, against these there is a formidable array of forces. These include:

That last point is a critical one, in my opinion. Admittedly, it’s familiar terrain for consistent readers of the EVAs I write. But there’s little doubt we have an extremely interventionist government running the country these days. By definition, this has serious negative implications for productivity but let me focus on one that I don’t think is getting the inflation attention it deserves (then, I’ll cover some of the other biggies that I see in this section):

Green Energy transition: Putting aside the existential (or not) risks that climate change poses, the extraordinarily ambitious agenda being adopted by Western countries (much less so in Asia) means that the costs are going to be staggering. This will also be the first time in human history that mankind will be moving from a more efficient energy source to a less efficient, at least in the relatively near future. Power costs for America overall are going to become more like they are in California and the Northeast states; i.e., excruciatingly high, especially for the poor. The amount of scarce minerals and commodities needed are also going to be astronomical and further ensure a very expensive transition. The International Energy Agency (IEA), a pro-Green Energy organization which has called for cessation of oil and gas exploration, has just released a comprehensive report on the challenges. It noted that if the US energy transition plan was adopted globally it would increase the demand for lithium, graphite, nickel and rare-earth metals by 4200%, 2500%, 1900% and 700%, respectively, over the next 20 years. Further, China controls much of the supply of these. (The Wall Street Journal reported on May 22nd, that China produces 90% of all manganese, an essential EV battery material.)

Politicization of the Fed. Even casual Fed observers readily recognize this is not the Fed of Alan Greenspan, much less Paul Volcker. It is now being tasked with fighting racism and climate change. Unfortunately, even before these were added to its mission statement, the Fed was struggling to maintain its independence and stay above the political fray. Until it is forced to recognize the inflation monster it has created, it is highly likely to maintain extremely easy monetary policies in the hopes of addressing social inequities. Sadly, though, high inflation is particularly tough on the poor and the elderly.

Entitlements. Other than a few lonely voices, like the new King of Bonds, Jeff Gundlach, Forest for the Trees author Luke Gromen, and my great friend Grant Williams, there is little attention being paid to the $150 trillion or so of unfunded entitlements resting on the shoulders of the US taxpayer. Of course, there is simply no way taxes can ever be raised enough to pay for these. Consequently, the choice is stark: either renege on the promises (a high likelihood for the wealthy) or have the Fed continue to create money by the trillions to buy the debt that needs to be issued make good on these commitments (and avoid social upheaval). Once again, this is a powerful upward force on inflation.

Triple digit oil prices. Shortages have already produced stunning price spikes in a wide range of commodities and I think the odds of that happening with crude are quite high. By summer, we should see global inventories below their long-term average and heading even lower. All of OPEC and Iran’s excess production will soon be desperately needed to avoid an acute shortage and oil north of $100. Anti-fossil fuel sentiment and the two near-death experiences the energy industry has had since 2014 is likely to greatly inhibit the usual production increase response to higher prices. With oil remaining ubiquitous in the global economy, a major price spike will have substantial inflation implications (and will probably be another reason the Fed keeps its MMM humming).

As these macro-economic mega-trends begin to lift consumer prices to uncomfortable levels, I wouldn’t put it past the current administration and Congress to resort to wage and price controls as Richard Nixon did in the early 1970s. It was a bad idea then and it will be bad idea again, should it be attempted. If you think this is improbable, consider that for years Western central banks have been controlling the most important price in a capitalistic system (to the extent we still have one): the cost of money, i.e., interest rates.

If you think I’m being too negative, consider Warren Buffett’s recent comments where he noted his sprawling business empire is seeing price increases everywhere. Moreover, he said their customers are accepting them.

More shockingly, famed Wharton professor, Dr. Jeremy Siegel, told the world via a CNBC interview last week that he sees inflation hitting 20% in the next few years. The amazing aspect of this is that Dr. Siegel is about as close to a perma-bull as you can find. (He is the author of the huge bestseller, “Stocks For The Long Run” and he does see a near-term market melt-up due to the trillions of fake money.)

He’s not alone in his strident warnings. The politically-influential and highly-connected Democratic economist Larry Summers made front page news last week with his blistering critique of the Fed’s current ultra-dovish policies, warning of the inflation risks it is running. Former NY Fed President Bill Dudley is also firing off alarming soundbites including of a future 4.5% Fed funds rate and that the days of low US treasuries yields are numbered. Michael Burry, one of the heroes of “The Big Short”, has amassed a $200 million leveraged short bet on long treasuries and has warned of a Weimar Republic type inflation threat in the US.

Yet nothing moves in a straight line in the real or financial world. Despite impressive long-term breakouts, almost all commodities look extremely stretched and poised for a sharp decline (some of which is already occurring). Economic growth readings such as we’ve seen lately are going to be very tough to sustain even as the enormous reservoir of consumers’ savings built up during Covid--fed by trillions of government hand-outs--is at least partially released into the economy. (Much will also be used to pay down debt and retained as savings; reasonable estimates are that about one-third will be spent, still a very large number.)

The cure for high prices is, as always, high prices—unless the government decides to slap on price controls which would only perpetuate the current shortages of nearly everything. But barring that, the present bottlenecks should ease in the months ahead, including of labor…assuming overly generous jobless benefit programs terminate.

If the economy and commodities cool for a spell, folks like David Rosenberg and Lacy Hunt are likely to be crooning in unison: “Inflation, we hardly knew thee.” And the Fed will be basking in self-congratulation over the vindication of its repeated “transitory inflation” assurances. But “transitory” is just a synonym for “temporary”. Consider these past government predictions of temporary: the income tax after WWI, payroll withholding during WWII, closing the gold window in 1971, and quantitative easing in 2009.

Only time will tell if the Fed is right or if inexorable inflationary forces are now at work. With millions of American investors heavily exposed to inflation victims like most stocks and nearly all bonds, any correction in hard assets is a chance to rebalance toward inflation protection securities such as what occurred recently with the gold miners. Perhaps even cryptos deserve a small punt as their recent battering far exceeds a normal correction—with Bitcoin last week briefly down over 50% almost overnight—befitting their hyper-volatile nature.

But my preference continues to be floating rate bonds and loans, including private credit, well-located income-producing real estate (i.e., in thriving, not dying, cities), energy securities, select producers of essential EV materials (like graphene), certain agricultural plays, and, of course, precious metals and the companies that produce them (after their big recent run, a pull-back is to be expected—and to be bought).

To wrap up, my overarching thesis continues to be that this is much like WWII when massive amounts of accumulated consumer savings were ready to be deployed. Once it was, the economy overheated very quickly, flummoxing all those who were expecting Great Depression 2.0. Shortly thereafter, inflation was in the mid-teens, something of which few Americans seem to be aware. But that is what allowed the US to get its debt-to-GDP down to around 55% from 110% in five short years. The problem was that bondholders got clobbered, losing double-digits in real terms for several years.

Accordingly, to chime in a bit with Messrs. Rosenberg and Hunt, we might not see terrific real (i.e., after inflation) growth, at least after a big growth spurt this year. Beyond that, we might see something like 3% real, with 7% inflation, for 10% overall or nominal growth. (If Jeremy Siegel is right, it might be 23% nominal!) With interest rates held artificially low by the Fed, the debt-to-GDP ratio will come down very rapidly, as it did 70 plus years ago. Sound too easy? Not really because the sacrificial lambs are likely to be both bonds and the US dollar. If I’m right—and I think it’s just a question of how soon events will play out along these lines—it will be imperative for American investors not to be as heavily exposed as they are now to US dollar-based assets--unless they offer significant inflation hedges. As I’ve warned before, that’s not how most are positioned —be they amateurs or professionals—despite how well hard assets have performed over the last 14 months. Eventually, there will be a resounding wake-up call that is heard by almost everyone but by then it will be too late…much, much too late.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.