"There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn’t true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true."

-SOREN KIEREGAARD, Danish philosopher and theologian

CAPE Fear Not? There is an old saying that a man who doesn’t stand for something will fall for anything. In my opinion, the same can be said of an investor. If participants in the financial markets don’t have some core principles to adhere to, they are going to be constantly swept up in manias, of both the bullish and the bearish variety.

As Warren Buffett has repeatedly observed, successful investing is simple but not easy. Under the simple heading, there are some fairly straightforward and readily-available guideposts that clearly indicate when stocks are over- or under-valued. One of them, however, is definitely not the market’s prevailing P/E ratio. Ironically, this is typically the yardstick that is most widely used. However, as I’ve written before, if you had looked at the market’s superficial P/E in 2009, stocks looked incredibly expensive because earnings had vaporized. Yet, equities were poised for one of their biggest ascents since WWII.

Another one to be filed under "not to use" is the once-vaunted Fed model that seeks to compare the attractiveness of stocks, or lack thereof, to interest rates. This theory, or variations on its theme, was trotted out repeatedly as recently as May by stock market bulls as a reason stocks should trade at above average P/Es. Yet, amusingly, after the near doubling of 10-year Treasury rates, that argument has gone into hibernation (be prepared for it to resurface should bonds keep rallying). The reality is that the Fed model, like so many of its elaborate theorems, hasn’t stood the test of time, as the Wall Street Journal’s Mark Hulbert, John Hussman, and others have convincingly demonstrated.

A far better approach is to use a valuation methodology that adjusts for the business cycle and the reality that corporate profit margins are extremely variable. Admittedly, this is a topic I’ve covered a number of times, but I’d like to offer up a surprising twist in this week’s EVA. Specifically, the experience of the last 20 years also calls into question the highly regarded Shiller P/E, alternatively known as the CAPE (cyclically adjusted P/E).

As my esteemed colleague Anatole Kaletsky, one of Europe’s most celebrated financial journalists has correctly noted, strictly using a below-average Shiller P/E as your buy trigger would have been, to say the least, frustrating over the last 20 years. It has only produced one truly unambiguous bullish signal since the early 1990s—at the beginning of 2009 (however, that was one doozy of a buy reading!). Consequently, Anatole and many investment pros feel the Shiller P/E has been discredited.

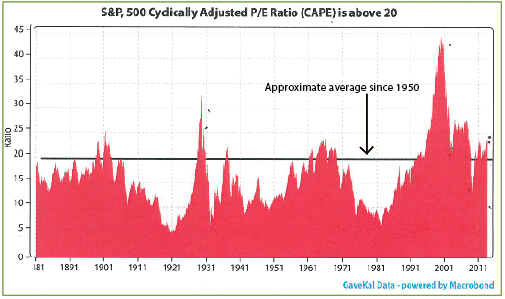

Per the chart below, it’s abundantly clear that the Shiller P/E has been a no-show for the last two decades when it comes to telling a stock investor when to be a buyer, other than during the aforementioned post-Lehman collapse.

But does this really mean the work of the man who presciently called both the tech and housing bubbles, unlike our dear central bank, should be relegated to the same dust bin as the Fed model?

Those who ignore history… First of all, Professor Shiller, the inventor and keeper of his eponymous P/E measure, has never suggested it was effective as a market timing tool. It was always meant to indicate very long-term under- or over-valuation. And despite being early, it did give a strident warning that stocks were inflated to an unprecedented degree in the late 1990s (almost totally due to insane prices for tech and telecom stocks which, sadly, was where almost all investment dollars were flowing at the time).

Second, a prudent investor should never rely on a single metric no matter how logical and well-proven. For example, Evergreen believed stocks were very attractive in early 2003, even though the Shiller P/E never fell below 21. Because the average CAPE has been around 19 since WWII, an investor who required a below-average reading would have missed the 100% leap that followed. Unquestionably, that was a big miss for devotees of the Shiller P/E.

In my view, a preferred approach is to look at a variety of proven valuation factors, including on sub-sections of the market. In early 2000, for instance, even though "the market" was beyond bubbly, outside of tech there was a plethora of exceedingly cheap stocks. But it took enormous fortitude for an investor to resist the pressure to keep up with the NASDAQ, ignore all the cocktail party bragging by his or her neighbors and in-laws (the latter, of course, being the most irritating!), and buy deeply depressed "old economy" stocks.

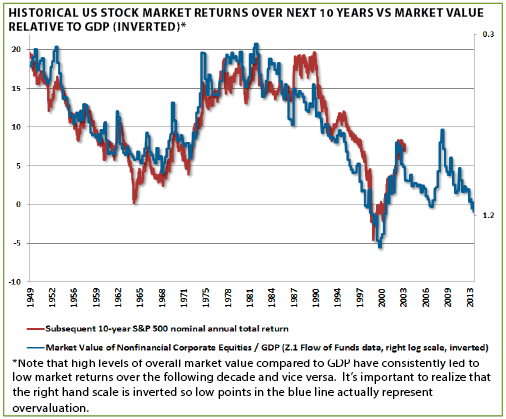

This was a classic case where if investors didn’t stand for something, like being willing to avoid the excesses of a mega-bubble, they were going to fall, and fall brutally hard, as millions did, taking trillions of dollars with them. The data were all there. Anyone willing to look at a CAPE chart or one of market value compared to GDP, or stock prices versus overall corporate revenue (i.e., the market’s price-to-sales ratio), or better yet, all of the above, knew that you had to be battening down the hatches by 1999.

If you got out too early, like 1997, when the readings first went postal, you still did just fine if you had the courage of your convictions and waited until the wheels came off in 2000 (or focused your buying on the non-tech sectors where cut-rate P/Es existed even in 1999). Unquestionably, that was a most profound "if."

One of the many advantages of being connected with GaveKal Research’s brain trust is the ability to do some mental jousting with them via email. It’s been my privilege to do just that with Anatole lately on the topic of the Shiller P/E, profit margins’ cycles, and various ways to determine whether the stock market is cheap or dear. (Anatole, by the way, believes the US stock market is breaking out into a new long-term up-phase.

Frankly, the dual stunners that Larry Summers has pulled out of the horse race at the Fed and, especially, Ben Bernanke’s Big Blink might mean that the monetary sluice will continue to runneth over. The betting line is now heavily in favor of Janet Yellen becoming the Fed’s first chairwoman, and her fondness for QEs is well-known. Thus, in the near-term, Anatole could well turn out to be right as this next phase of "pseudough" creation hits its resounding crescendo. (Personally, I believe we are moving into a long-term taper era, regardless of who heads the Fed, barring a major face-plant by stocks.)

The blow-off stages of aging bull markets are, despite the thrill and euphoria of seemingly easy profits, where the really big money is lost in the next downturn. To avoid that outcome, perhaps the Shiller P/E, combined with a few other indicators, might have some information value after all.

…are doomed to repeat it. Looking closely at the chart above of the CAPE, or cyclically adjusted P/E, it’s quite clear that the late 1990s caused some serious distortions. What previously had been expensive became cheap based on comparison to the absurd valuations seen at the dawn of the millennium. Prices were so out of whack with reality that it might be another thousand years before we see them again. (A close study of that chart also strongly suggests that we haven’t fully worked off the excesses of the 1990s.)

But this is where some tweaking to the Shiller/CAPE comes into play. In early 2003, the bear market that started in March of 2000 had been going on for nearly three years. The CAPE had also been cut in half (admittedly, from an astronomical peak of over 40), definitely up there with one of the most severe de-ratings of all time.

Which brings me to the conditions today. Equities have been marching north for four and a half years while the Shiller P/E has increased from 15 in 2009 to 24 today, or 60%. Both of these indicate a stretched market. For example, using the 2003 bull run as a comparison, one of the few that began with a CAPE higher than this one did, the expansion was just 28%, from 21 to 27 (ironically, the 1890s bull market also started at a CAPE of 15 and increased to 25, which is almost exactly the most recent reading, but that’s going back even before I was in the money management business!).

It should also be quite clear that the episodes of truly massive and long-lasting P/E expansion started from very low bases like 1921, 1932, 1941, 1974, and 1982. We never got close to those fire-sale levels five years ago, even during the worst days of the global financial crisis. Therefore, to expect an enduring and significant extension of the bull market from here would be defying a century and a third of market history.

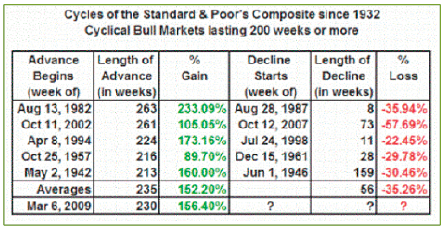

Then there is the issue of time, actually time times two. Per the chart below, the longest advance of the last 70 years ran for 263 weeks, and our current bull is at 230 weeks.

Admittedly, if this one should match the 1982 run, it could last another 33 weeks, and rise another 73%. But, is it realistic to expect this from a market that started at 15 times cyclically adjusted earnings, vs 7 times? Of even more significance is what happens, per the far right hand column, once these big bulls finally run themselves into the ground. The fact of the matter is, regardless of how much they escalate or how long they last, the reversal is always deep (even the relatively mild 1998 retrenchment was followed less than two years later by one of the worst bear markets ever, with the nucleus of the speculative frenzy, the NASDAQ, atomizing nearly 80%).

The other "time" issue that I believe should concern investors is literally an issue of Time. This was the cover of that august periodical’s September 23rd edition (note, I did say august, not August):

Barron’s Randall Forsyth, who now writes the Up and Down Wall Street column after the iconic Alan Abelson‘s passing, picked up on this danger signal last week when he wrote: "The appearance of bulls and other positive images of the stock market on the cover of general-interest magazines has been a redoubtable contrarian indicator since, well, Henry Luce came up with the idea of Time magazine in the 1920s."

Quoting the empirical work of Paul Montgomery, who has done exhaustive studies on the phenomenon of magazine covers as wrong-way bellwethers, he wrote: "There’s an 80% probability the market will top in a month and will be lower a year from now."

Yet, the multitude of investors who are turning a blind eye to history appears to be willing to bet on the 20% outcome. Call me gutless, but I’m not particularly fond of those odds, especially when there are so many other warning flags flapping hard in the wind.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. All of the recommendations and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Information contained in this report has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Evergreen Capital Management LLC makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, except with respect to the Disclosure Section of the report. Any opinions expressed herein reflect our judgment as of the date of the materials and are subject to change without notice. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their financial situations and investment objectives.