“The recent collapse is the climax, not the end, of an exceptionally long, extensive and violent period of inflation in securities prices and national, even worldwide, speculative fever.”

–Business Week (now Bloomberg Business Week), November 2nd…1929!

“We’re in a hell of a mess.”

–Former Fed chairman PAUL VOLCKER in a New York Times article in late October of last year, just as the US stock market was beginning to crack

At the beginning of 2018, we initiated a new EVA series titled “Bubble 3.0” with excerpts from David Hay’s upcoming book titled “Bubble 3.0: How Central Banks Created the Next Financial Crisis”.

If you are just joining us in the middle of this ongoing series, which will eventually culminate in a full-length publication, please take a few moments to review the prior installments in the series:

In this month’s edition, David continues his exploration into Bubble 3.0 by looking back at the truly ridiculous hysteria that surrounded Bitcoin mania at the end of 2017, before diving more deeply into how central banks have contributed to globally-inflated asset prices over the past decade.

(Editor’s Note: Given the length of Chapter 9: What Price Prosperity, we will run this edition of EVA in two parts. The second edition of this issue will be published next week on Friday, January 18th.)

WHAT PRICE PROSPERITY? (PART I)

In a prior Bubble 3.0 EVA, I’d mentioned that my intent was to write a chapter on the eventual costs of the frantic efforts by global central banks to artificially create economic good times. It was a little over a year ago, as Bubble 3.0 inflated to gargantuan dimensions, when I accidentally kicked off what would become a book written in real-time. The unintended inaugural issue, titled “Bubble-Watch”, was published on December 22nd, 2017, several months before I had decided to formally write “Bubble 3.0”.

The reason this timing matters is that it almost precisely coincided with the peaking of the most outrageous speculative frenzy of this particular era, Bitcoin mania. As you may recall, what happened in late 2017 involved many other derivatives of Bitcoin, the multitude of crypto-currencies. The rapid proliferation by these strange things (frankly, I’m not sure what else to call them) at the end of 2017 and into early 2018 called into question one of the supposed prime attractions: their scarcity value.

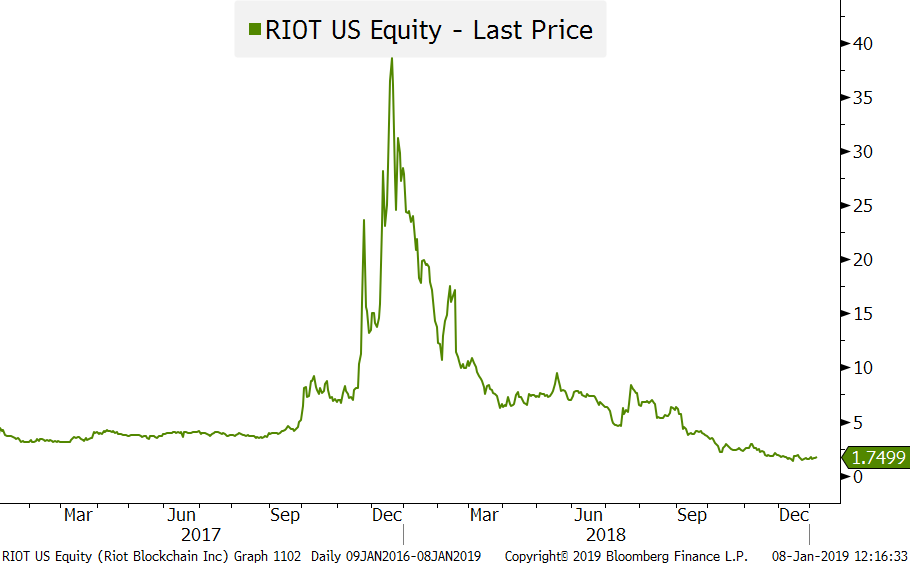

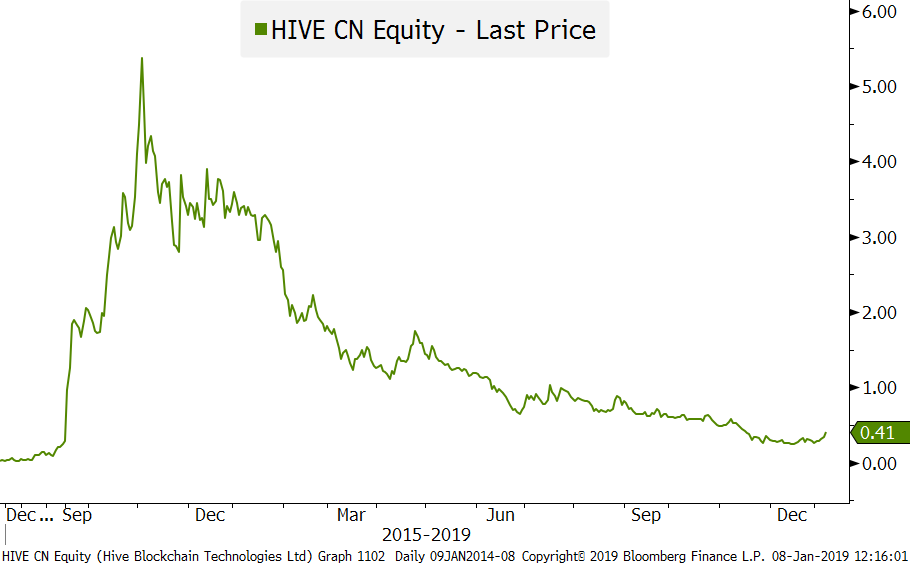

You may also remember that this bubble, which actually eclipsed the greatest asset inflation previously seen in human history—the Tulip Bulb insanity in Holland during the early 1600s—involved more than just the cryptos themselves. As chronicled at the time in the “Bubble Watch EVA”, numerous US companies cynically exploited investor fascination with cryptos and the related blockchain technology. Several companies – some with businesses not even closely related to blockchain tech – changed their name to include blockchain and saw their share prices rise astronomically.

This behavior was a virtual clone of the bad good old days of the late 1990s when many companies added .com to their name in order to create a hockey stick ascent in their stock value. As is typically the case, the illusion of easy profits sucked in unsophisticated investors—not to mention many momentum-chasing professional “money-managers” (perhaps more accurately, mis-managers). In nearly all instances, these moon-shot price moves were followed by equally stunning collapses.

At one point, the combined valuation of the Bitcoin/crypto/blockchain “sector,” including the related stocks, approached $1 trillion, roughly equivalent to the market capitalization of the S&P real estate companies. A chart of what happened next is shown below.

During this phase, Evergreen received an unusual number of queries from our typically conservative client base asking for our thoughts. An initial trickle turned into a torrent of calls and emails as the price approached $20,000, up from less than $1,000 just months earlier. Our team consistently advised that this had all the classic characteristics of a bubble, including a sexy story and an almost impossible-to-disprove valuation calculus. (Who really had any idea what those “coins” were worth other than the last quote?)

CNBC fed the frenzy by offering extensive air-time to those infusing helium into the ever-expanding blimp. A series of telegenic and persuasive Bitcoin boosters would throw out audacious price targets and for many weeks those would be hit almost instantly. This, of course, gave them great credibility in the minds of the millions around the world desperate to get in on the action.

(To its credit, CNBC recently aired a segment devoted to the shows they had done with the bubble-blowers at the time. It was fascinating—and borderline hysterical—to see how ridiculously wrong their forecasts turned out to be. One of the glibbest was at it again, in a follow-up interview, insisting, even now, that it’s just a matter of time before Bitcoin hits $150,000. You’ve got to give him credit for chutzpah, if not contrition.)*

It’s hard to know how much wealth was created and then almost instantly destroyed globally (the crypto craze was very much a global phenomenon) through this extreme manifestation of human avarice—and stupidity. But a conservative estimate is in the hundreds of billions; a more realistic guess is well over a trillion considering how much was lost by directly investing in Bitcon Bitcoin and some of its kindred (evil) spirits (i.e. other cryptocurrencies and stocks such as those shown above).

At the time, we commented that it wasn’t so much the value vaporization that was the big issue with the cryptos. Rather, we felt (and still do) that it was what it signified: the most grotesque example of global central bank policies that drove asset prices to absurd levels. Of course, they would never admit that their goal was to push them that high. But it would take a state of denial rivalling the Saudi government’s over the murder of Jamal Khashoggi for any central banker to not realize the extreme nature of what they have wrought.

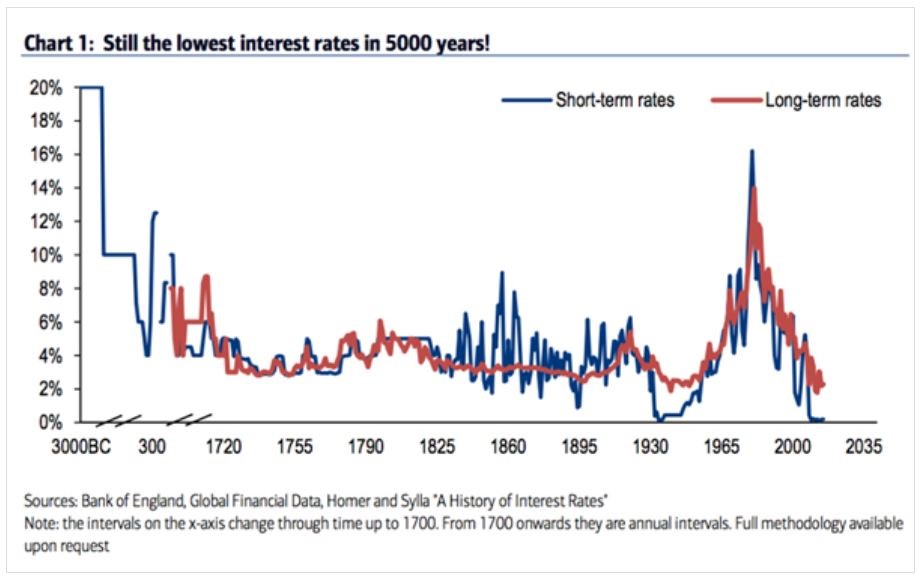

The mere fact that at one point over $10 trillion of bonds globally had negative interest rates was really all the proof any rational person should have needed. (Incredibly, there are still $7 ½ trillion worth of debt instruments where lenders must pay borrowers for the use of the former’s funds.) As we wrote in the September 21, 2018 edition of “Bubble 3.0”—“The Biggest Bubble Inside the Biggest Bubble Ever”—the reverberations of so flagrantly and recklessly distorting the cost of money were bound to produce a series of mini-bubbles, not to mention a few of the maxi-variety.

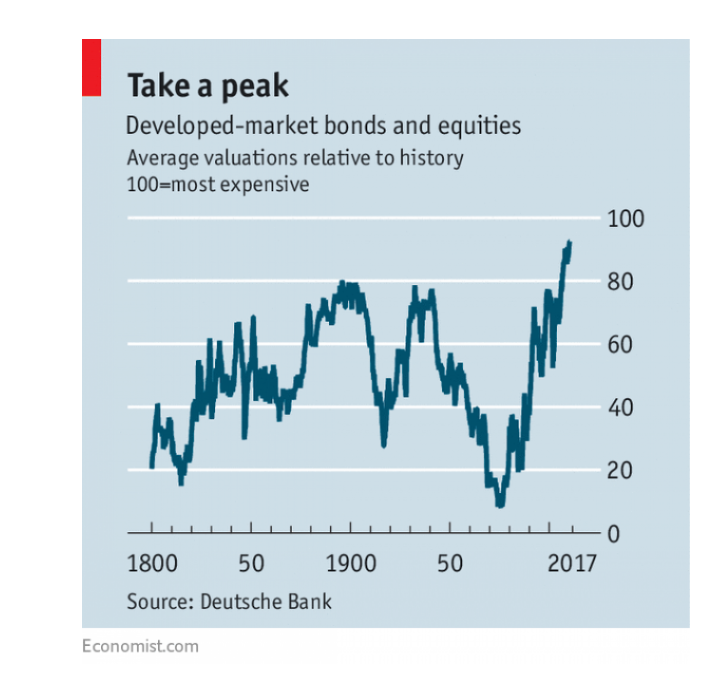

A brief excerpt from that EVA helps drive home this point: “If one accepts the reality…that recent years have seen the lowest interest rates in 4000 years, then how could we not be at least going through a massive bubble, if not, as I’ve contended, The Biggest Bubble Ever?

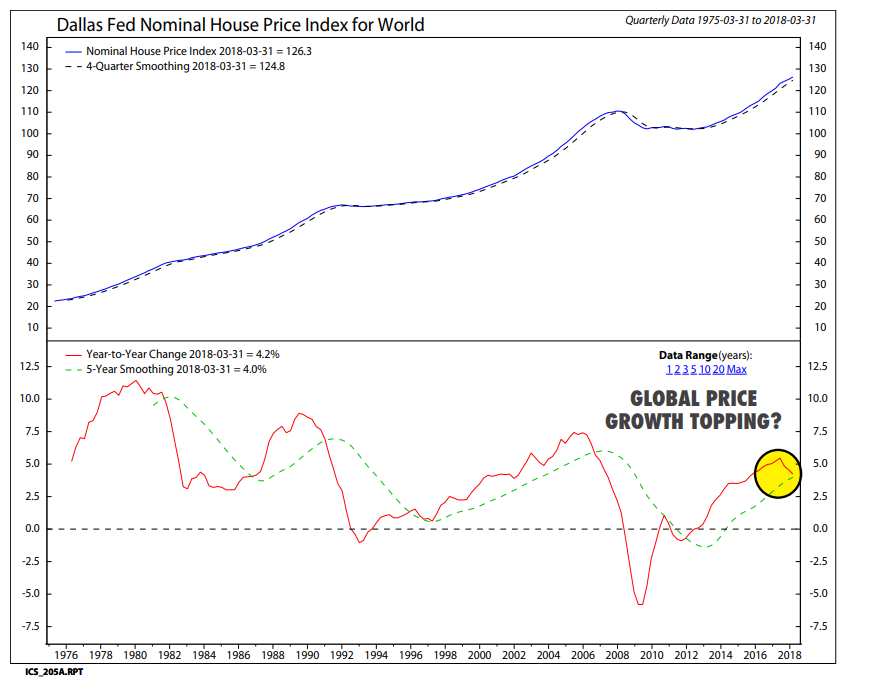

On that score, might there be more than just a casual connection between the charts down below? Or is it actually more like a causal connection? Despite the myriad perma-bull pundits who have long denied a linkage between QE-mania and obscenely inflated asset values, there is no doubt in my mind about the cause-effect relationship between the two.”

Yet, for most of the past year since I’ve been on this bubble-busting crusade, I have felt like one of those Old Testament prophets who were about as popular in their day as a plague of locusts. It’s simply human nature not to want to hear that the good times are based on a false premise—that free money can create prosperity—and, more importantly, that they can’t, and won’t, last. Bummer! But more of a bummer is to be victimized by the inevitable return to reality.

For sure, this reasoning has been a very hard sell—like pitching a faith-based story to Hollywood (been there, failed that)—even as a growing list of assets around the world began to break down. As long as the S&P 500 was still charging higher, even though it was being led by a shrinking number of stocks, the theme that the entire economic and financial environment was at grave risk played about as well as an old Frank Sinatra tune at a rave.

Ironically, September 21st of last year, the date we ran the “Biggest Bubble Inside the Biggest Bubble Ever” EVA, was almost precisely the breaking point for the formerly titanium-ribbed S&P 500. What has happened since is shocking, even to worry-warts such as yours truly. It’s not that the damage to the index has been all that severe. As I write this, the main US index is down just 12%, which is really nothing more than a standard-issue correction. But there are a few things that make it seem much worse than this unremarkable number.

First, the fact that it has dropped at all after so many years of slow but relentless appreciation is stunning in its own right. Thanks to the manipulations of those clever monetary mandarins (thank you, Jim Grant for that apt label)—including direct purchases of equities with fabricated funds—investors had come to believe that the US stock market was a magical money machine and not the wickedly unpredictable beast it has been ever since its genesis over two-hundred years ago.

Second, what had been an almost volatility-free environment, at least of the downside variety, suddenly became, in early October, one of the most turbulent markets seen in many years. And, unfortunately for the never-say-sell crowd, the bulk of the extreme fluctuations have been in the wrong direction.

Thirdly, and most importantly, the damage done to the majority of US stocks has been far worse than the aforementioned 12% pull-back in the S&P. In fact, with nearly all of the former darlings (read: the FAANG stocks) having suffered 20% to 30% swoons, and a host of less adulated issues having tanked 40% to 70%, it’s amazing to me that the official index is down as little as it is. This development, as noted in the December 14, 2018 EVA, has caused me to refer to this as a two-tier market. In other words, it is characterized by a crowded (though less so) cohort of still-overpriced stocks alongside a growing raft of bombed-out issues trading for single-digit P/E ratios. For example, check out the 50 times earnings valuation of the largest publicly-traded Mexican food chain, with a history of serious food-safety problems. Then contrast that with one of the nation’s largest and most content-rich media companies trading at a mere nine times what it earned over the past year (i.e., past, not hoped-for earnings).

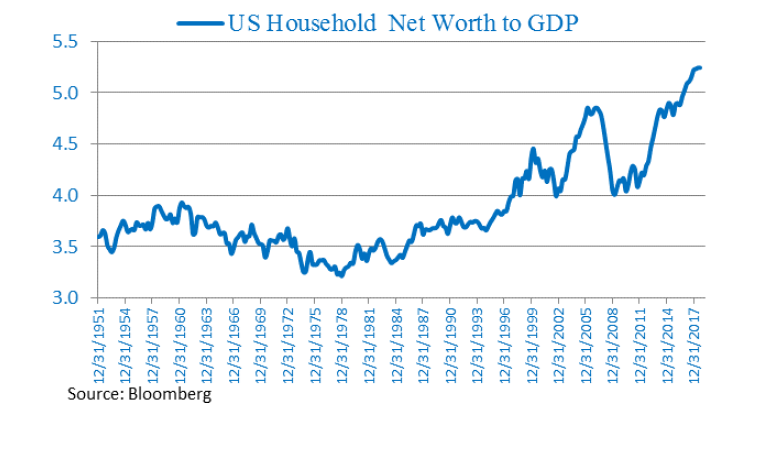

Putting that puzzle aside, the fact that a 12% drop in US stocks represents about $4 trillion of lost shareholder value is still a very large number—and it is likely to have an equally large impact on consumer attitudes. This is a reality that is already showing up in previously Himalayan-high consumer sentiment surveys. You may have noticed, lately those have been cracking, as are a wide range of leading economic indicators. (As a topical side note, last Friday, January 4th, 2019, the US stock market had another one of its spectacular rallies, sending the Dow up nearly 750 points. In Evergreen’s view this is once again a typical bear market eruption, in this case caused by a strong jobs report. The flaw in the logic that this release indicates a robust economy is due to the fact the unemployment rate is among the most backward-looking datapoints. A much more future-focused measure is the Purchasing Managers New Order Index which collapsed by a jaw-dropping 11%, as reported on January 3rd.)

It is this nearly overnight multi-trillion dollar net-worth disappearance--caused by pumping up asset values to precarious heights—that seems to have been lost on all the central bankers who have been convinced free-money was the answer to all that ails the planet. Frankly, up until lately, questioning the end-game seemed like an exercise in sour grapes for people like myself. The fact that the Great Reckoning has been delayed for many years has made the non-believers among us seem churlish—if not downright foolish (I’ve certainly heard plenty of the latter feedback).

To be fair to the monetary powers-that-be, their belief was always that economic growth would become vigorous enough as a result of their collective $15 trillion asset levitation that they would then be able to raise rates to more normal levels without causing major disruptions. This is what I’ve long referred to as The Immaculate Correction scenario. A year ago, with the world supposedly enjoying a “synchronized global expansion”, that seemed somewhat plausible—until various markets around the world began to break down.

The central banks also hoped the same would be true with said $15 trillion of QE (quantitative easing) that would theoretically need to be taken off their balance sheets, mostly bonds that have been bought with fake money. This is what the Fed is currently attempting to do at a $50 billion per month clip, a process becoming widely known as Quantitative Tightening.

For well over a year, numerous prior EVAs have been warning about the dangers posed by the first ever “double tightening” (i.e., both raising rates and reversing a decade of QEs). As with most of my warnings, these have been largely dismissed, even ridiculed—until recently. It’s now become inescapably clear that the Fed is in a no-win position, as I’ve previously speculated. The new King of Bonds, Jeff Gundlach, was interviewed at length on CNBC right before Christmas and he summed it up perfectly, in my view: “The Fed is damned if they do and damned if they don’t.”

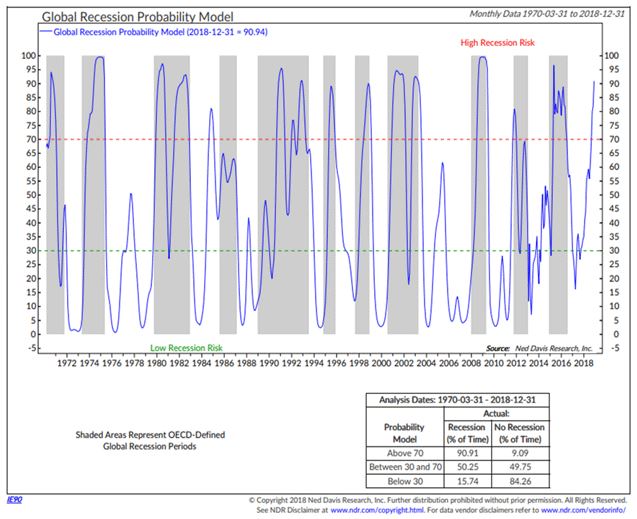

In other words, if it keeps tightening, it risks further roiling financial markets and increasing the already rapidly rising worldwide recession risks (per the below chart from Ned Davis Research). Yet, if the Fed stops now, it sends a signal that it’s caving into presidential pressure and/or that it’s more worried about the economic outlook than it officially admits.

Ergo, we’ve gotten to the point where the markets are no longer blowing off the double-tightening as they did for so long. Now, instead, each new hike creates severe consternation among investors. Moreover, the threat of being “a long way from neutral”, as Fed Chairman Jay Powell innocuously, but now infamously, mused in mid-October, injects sheer terror into the hearts and minds of the once-fearless blundering thundering herd. For sure, another propellant of the 746 point rally in the Dow on January 4th was Fed Chairman Powell hinting at a joint speech event with former Fed heads Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke, that it might not raise again, at least anytime soon.

Despite the initial euphoric reaction, hints of a pause strongly suggest that the Fed is worried that economic conditions are weakening (a view which is becoming increasingly hard to dismiss). In that regard, it was somewhat comical to hear Mr. Powell wax so proudly about the jobs market while suggesting conditions might not be healthy enough to withstand interest rates much above the current inflation rate. (By the way, the Fed has never before halted a rake-hiking phase with the fed funds barely above inflation. Yet, we would agree with those who think this time is truly different.)

But the really sobering news, for anyone who performs even a cursory review of past Fed pauses after long hiking campaigns, is what happens next. As one of the most influential and independent-minded economists, David Rosenberg, has repeatedly pointed out, previous cessations have been right before bear markets and/or recessions.

It’s further become obvious that one of Evergreen’s long-held beliefs is being validated; namely, that the global economic and financial systems have scant ability to withstand tighter monetary conditions. The fact that a 2 ¼% fed funds rate has caused worldwide disruption and what is likely at least $10 trillion of market value evaporation globally is proof-positive of this reality.

Frankly, it’s incredible that such carnage has occurred with what are still essentially zero interest rates in Japan and most of Europe. Perhaps the most stunning example of this is in economic juggernaut Germany, where the 10-year government bond yield is a teensy-weensy 0.2%. That’s right, 2/10s of one percent, known in the financial game as 20 basis points (or, even more colloquially, 20 bips). Even the US has interest rates that used to be reserved for times of acute distress.

When markets were soaring a year ago, and the S&P was looking like it would rise for 10 straight years for the first time ever (a streak that came to an end thanks to the terrible fourth quarter), lonely voices like ours warned against victory dances by the central banks. A classic example of this was the highly self-congratulatory press conference Jay Powell gave in early October. Ironically, his ebullience and, of course, the aforementioned statement about the fed funds rate being a long way from neutral, coincided with the brutal sell-off since then. As they say, pride goeth before the fall…and this has been one heck of a fall for the average US stock, despite the post-Christmas bounce.

My main dissent from the conviction that the grand QE experiment had worked wonderfully was that such a conclusion wasn’t possible until we went through the next bear market and recession. Until then, we wouldn’t be able to determine how much damage would eventually ensue. In other words, we wouldn’t know what the real cost of this central bank force-fed prosperity was (I would argue pseudo-prosperity) until the tide went out—which, with many asset classes, happened with a pre-tsunami-like swiftness.

As many have noted, including this newsletter, the $15 or so trillion the planet’s monetary magicians conjured up produced the weakest recovery ever in the post-WWII era, including in the star-performer, the US of A. Consequently, the “economic gain” so desperately sought has been negligible. Again, I ask, what price prosperity?

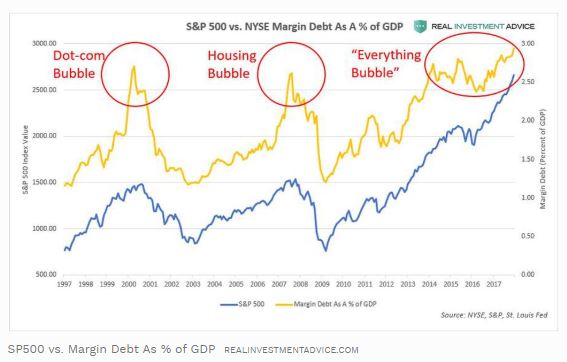

In next week’s continuation of this chapter on that pressing question, I’ll delve more into the risks that have been allowed to accumulate to massive proportions. But, in the meantime, I’ll close with this visual on margin debt and the S&P 500, showing the status back in September, right before the bottom fell out. It’s also a simple and concise summary of Bubbles 1.0, 2.0 and, last, but far from least, Bubble 3.0.

*While I am both frustrated and embarrassed to have underestimated how long Bubble 3.0 would last, I do take solace in having been extremely vocal about the lunacy of the crypto-currency mania. We don’t expect any kudos, but long-time Evergreen clients and EVA readers (since 2005 when this newsletter began) may recall that this is at least the fourth bubble we called out before the implosion. (Tech in the late 1990s, Chinese stocks in 2007, and the housing market from 2005 through 2007.) We think Bubble 3.0 will add to that list, despite its long-postponed rendezvous with reality. If, and when, it does, the current measly 4.8% return including dividends on the S&P 500 since 12/31/99 will become even more underwhelming.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

LIKE *

* Due to the severity of the recent market selloff, we have reduced our equity underweight from 50% to approximately 43%.

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

* Credit spreads are the difference between non-government bond interest rates and treasury yields.

** Due to recent weakness, certain BB issues look attractive.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness. Securities highlighted or discussed in this communication are mentioned for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation for these securities. Evergreen actively manages client portfolios and securities discussed in this communication may or may not be held in such portfolios at any given time.