“Impressive scholarly research has demonstrated that the government spending multiplier is in fact negative, meaning that a dollar of deficit spending slows economic output.”

-Economist and bond manager extraordinaire, LACY HUNT

“And you experts in the law, woe to you, because you load people down with burdens they can hardly carry, and you yourselves will not lift one finger to help them.”

-JESUS OF NAZARETH

Big government, even bigger sins. This month’s Gavekal version of the Evergreen Virtual Advisor is occurring slightly out-of-sequence. The reason is due to my belief that the “Ideas” piece from Charles Gave highlighted in this issue serves as a nifty follow-on to last week’s EVA, “The 5 Cs: Could Congress Create Consecutive Crises” (click here to view). The lead title pretty well sums up the thesis I was posing: a) Congress was a key actor in the housing horror story and b) that it is busy messing things up again with its “war on the private sector” behavior.

To be clear, I was not alleging that the two specific companies mentioned last week were guilt-free. As I noted, Wells Fargo clearly bungled the fraudulent account scandal and ITT Educational was, as I also observed, a dodgy operator. The key point I was conveying was the double standard on the part of Congress. What it perpetrated in the build-up to the housing crash was far more injurious to our country than what Wells did wrong. Yet it sat in sanctimonious judgment of the bank and its CEO like an avenging angel. It’s similar to a crooked traffic cop throwing a speeding driver in jail when the cop had previously committed vehicular homicide and gotten off without even a warning. (In the case of ITT Educational, the double standard involves a competitor of theirs who has avoided prosecution despite worse performance metrics and has extravagantly compensated an ex-US president.)

Think about it for a moment. Back in 2000, we had a booming economy and our government was running budget surpluses (under a democratic president, by the way). Alan Greenspan, the Fed chairman at the time, publicly worried about all US treasury debt being paid off by 2010 (another in a long line of massive prediction misses by “the maestro”).

Today, GDP growth is barely above recession levels and government debt rose by $1.4 trillion in the most recent Federal fiscal year—despite the fact the official deficit was less than half that amount. Instead of paying off all our debt, it has surged by over $10 trillion in a mere ten years, basically tripling the outstanding balance at the beginning of the millennium. Sixteen years isn’t a long stretch of time, but the degradation of our economic condition over that period is stunning—notwithstanding the S&P 500 behaving like all is hunky-dory.

There’s little doubt (in fact, I’d say none) that the prime cause for today’s sclerotic global economy and the debt-drenched status of almost every “rich” government was the global financial crisis (GFC). And the primary catalyst for the GFC was unquestionably the bursting of the housing bubble. Ergo, it’s important to determine who really caused that catastrophe. Congress wasn’t the only perp. The Fed certainly deserves considerable blame, as does Wall Street, which behaved in its typical “when the ducks are quacking, feed them” fashion. But Congress and the Fed were either egging on “The Street” or turning a blind eye.

Charles attacks the economic malaise of the new millennium from a somewhat different, but related, angle. Like me, he makes his case for government policies having been a huge part of the problem. But he looks at it from the standpoint of the abysmal failure of what he calls “the euthanasia of the rentier” (using the term first coined by John Maynard Keynes, the father of Keynesian economics). In simpler language, this means the shafting of the investor class. The process has many surprising victims, including folks like the participants in the Dallas Police and Fire Retirement Fund, which is in such horrific shape it makes Obamacare look healthy. (Don’t take my word for it on the latter; Bill Clinton recently called the Affordable Care Act “the craziest thing in the world”.) The retired, or soon-to-be-retiring, baby boomers are another casualty of this euthanasia as they discover that instead of living a life of leisure on a fixed-income, it will be more like praying to survive on a nixed-income.

What Charles persuasively articulates is that the last decade and a half has seen highly interventionist government policies in the US, while in his native country of France the “government to the rescue” model has been in place for nearly 50 years. As a result, nearly 60% of the Fifth Republic’s economy is government-driven—as into the ground.

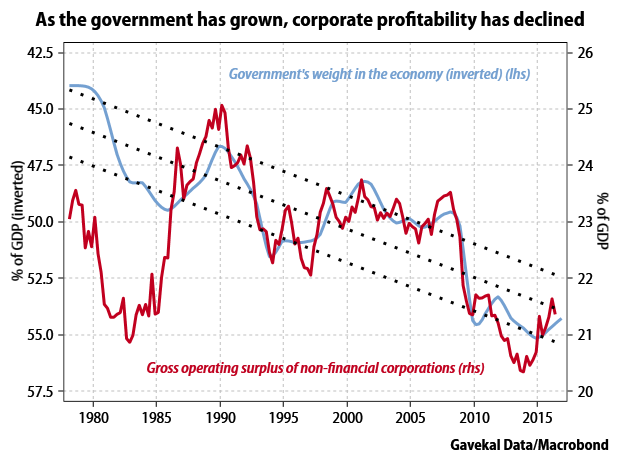

Though he doesn’t point this out, it was fascinating for me to closely study the charts on France and see that the only time Charles’ homeland enjoyed a meaningful growth thrust was from about 1982 to 1990. Unsurprisingly, this was when the government’s share of GDP dramatically receded. Yet, for the most part, since 1970 the French public sector has been methodically encroaching and enveloping the private sector. The result has been steadily worsening economic stagnation.

As Charles also points out, other countries such as the UK, Germany, Sweden, Canada, and Australia, to name a few, have in the past realized the error of their socialistic ways and rolled back the government strangulation. As prior EVAs have noted over the years, it’s often been the left-wing parties that have performed this counter-intuitive pirouette, typically out of sheer desperation.

The most disturbing part of his analysis relates to what he has long called the “five cardinal sins” by policymakers: war, protectionism, increased regulation, massive monetary mistake, and tax increases. In case you haven’t noticed, the US has committed at least four of these transgressions already, with the fifth—anti-trade policies—looming likely due to populist impulses on both the loony left and the rabid right.

Since at least 2011, Charles has been warning that current policies by most developed governments were leading to stunted economic development. Years and years of real-world results have confirmed his once rogue beliefs. Therefore, I’d suggest his current thoughts are very much worthy of your careful consideration.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

By Charles Gave

Keynesian beliefs are based on two key ideas. Firstly, recessions are caused by an excess of savings among nasty types known as rentiers. Secondly, if there is a shortage of demand, the government should conjure it up out of thin air by borrowing money to spend as needed. In the last few years we’ve seen what happens when the first of these two ideas is put into practice. Policymakers around the world have attempted to euthanize the rentier, and the result is the current “secular stagnation”, a phrase which is nothing more than a polite way of acknowledging that their policies have failed miserably. While this failure has come as a surprise to the Keynesians, no reasonable human being could rationally have expected any other outcome (see The High Cost Of Free Money).

Albert Einstein supposedly said that the definition of insanity was to repeat the same mistake time after time expecting a different result (although a quick check reveals a more likely source of the quote to be the Betty Ford Center). Nevertheless, Keynesians are nothing if not persistent. Having failed to “stimulate the economy” by manipulating the price of money, they are starting to conclude that the world faces a “lack of final demand”. And their solution is that this lack of demand should be counteracted by an increase in government spending. So the question now is this: is the second—fiscal—shoe about to drop? And if it does, will the results be any better than those produced by tampering with interest rates, or even worse?

My contention in this paper is that just as attempts to stimulate the economy by maintaining abnormally low interest rates have always failed, so too has every attempt in modern history to procure growth through increased government spending failed. And the economic system can hardly support another massive policy failure.

We may live in a “post factual” political world, but I’m old fashioned and like to start a research project by identifying facts. Next I seek to find a theoretical explanation for the relationships which appear to exist between them. I’ve always found the best way to do this is to re-read the great economists who lived and worked in the days before the invention of computers—when economics was a branch of logic and not of astrology.

I established some time ago the fact that the first Keynesian shoe to drop—the euthanasia of the rentier—always causes a structural decline in gross domestic product, and pieced together the explanation of why this must be so. In the case of the second shoe, I have argued before that if government spending starts to go up as a share of GDP, then the structural growth rate tends to quickly decline. So what I need to do at this point is, firstly, to establish beyond doubt the fact that any structural increase in government spending as a share of GDP in the past has always led to a decline in the structural growth rate of the economy, and secondly, explain theoretically why it could not be otherwise.

As I have observed before, Keynesianism is to communism what Coke Light is to the real thing. In neither system is there a properly functioning market. Instead the markets are “controlled” by smart social engineers, so smart in fact that they claim to be able to carry out the adjustments necessary to guide the markets in real time. Of course, the difference between the two systems is that the original version had the gulag, which the derivative does not. But the intellectual framework is much the same: both insist that capitalism does not work.

One developed country that has oscillated back and forth between communism and Keynesianism over the last 35 years—with its communist sectors growing remorselessly as a result—is France (although Japan could also rate a mention). Admittedly, France doesn’t send its dissidents to the gulag; it just sends them into exile instead.

So I will start my demonstration with my beloved homeland. But I could have gone through the same exercise for the UK, the US, Canada, Japan, or Sweden and the results would have been similar. If readers want, I will be happy to provide them with the same charts for any one of these countries as I show for France in the following pages.

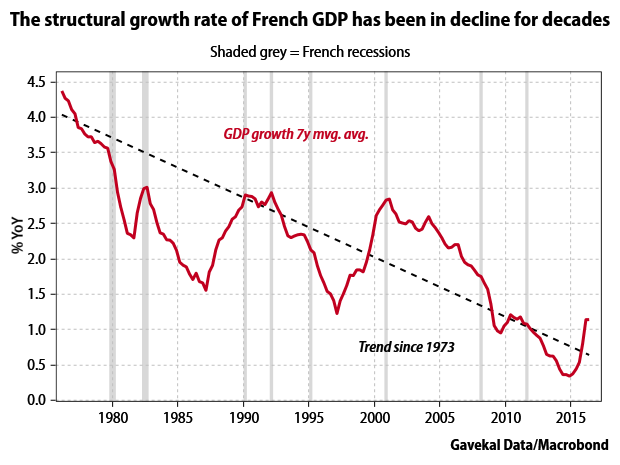

I shall begin with a statement of fact: the structural growth rate of French GDP has fallen relentlessly since 1973, as shown in the chart below. It can be seen that the structural growth rate of France’s economy, shown here by the seven-year moving average, has fallen from around 4.5% in the early 1970s to 1.1% today.

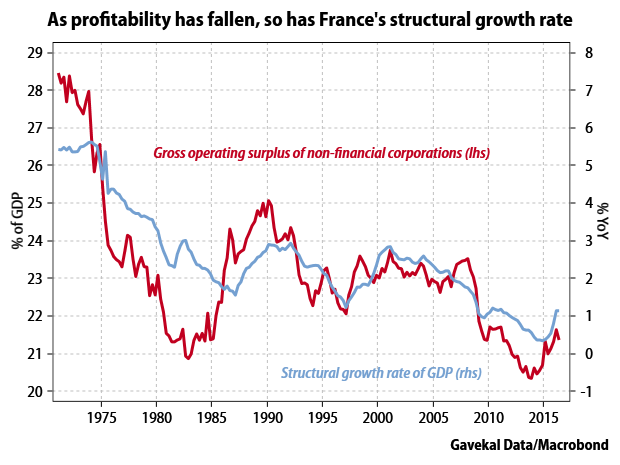

So, what is the explanation for this decline? My hypothesis is that France’s structural growth rate has fallen because corporate profitability has been dropping relentlessly ever since 1973, as shown in the first chart below. The economy got structurally weaker because the private sector got weaker. Of course, this answer is unsatisfactory, because it leads automatically to the next question: why has corporate profitability declined so much? The explanation can be seen in the second chart below.

So the relationship seems to work like this: the bigger the size of the government relative to GDP, the lower the gross operating margin of the corporate sector, and the lower the growth rate of the economy. Now we are making some progress. The bigger the government, the lower the level of corporate profitability, which makes sense, since paying for the government is part of the overhead for any company.

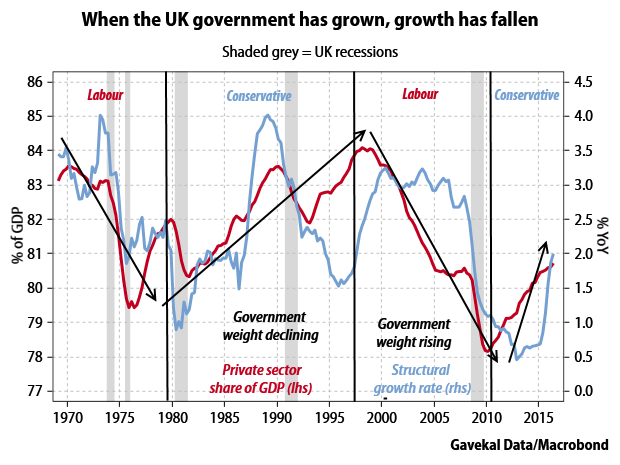

The relationship appears to hold for France. But in France the political system has moved consistently in one direction. Does the same relationship apply to other countries where the political system has varied more over the years than in France? We can check this easily enough by looking at the United Kingdom, which has alternated between episodes of Keynesianism when the Labour Party was in power, and periods of conservatism when the Tories were in charge.

Three conclusions leap out from the UK chart below:

1) The bigger the government, the lower the growth rate. The smaller the government, the higher the growth rate.

2) The structural decline in the growth rate of GDP is much less pronounced in the UK than in France.

3) The structural rise in the government’s weight in the economy is also much less pronounced than in France, since there were two periods in which Conservative governments managed to roll back the frontiers of the state—from 1979 to1997, and from 2010 onwards.

The electoral cycle in the UK seems to be: the Labour party grows the government for a few years, and then the Conservatives come in to downsize the state to the level where it was when they were fired. As soon as the Conservatives have done their duty, the British people vote again for the Labour party. No such thing has happened in France as regardless who was in power, they all grew the state. Since 1973 at least, it has been impossible to tell whether a particular period had a left wing or right wing government based on a ratio of government spending to GDP.

Based on these observations I would make the following statement: For the economy to grow structurally in the modern era, what is required is less government spending, not more. The idea that growth can be stimulated by cutting government spending is hardly “mainstream” although even a casual perusal of the data shows this to be the case. In the following section I shall offer a theoretical explanation for this reality.

Let’s start with the obvious point. In the communist part of the economy (57% of French GDP) there is, by definition, no “creative destruction”. Hence, to borrow from the biblical parable of the talents, ever more capital ends up with the latter day equivalent of the “the bad servant” who buried his talent. Hence, whatever the (good) intentions, the economy is put on a path straight to an (ex-growth) hell. The key lesson is that if the part of the economy which is growing the fastest consumes more capital than it generates, the economy must necessarily move ex-growth.

A slightly more subtle explanation stems from a notion developed by economists in Austria more than a century ago—namely, “marginal’” analysis. In a proper market economy an entrepreneur must deal with three variables: the cost of labor, the cost of capital (both are certain) and the expected return he hopes to make, which is anything but certain. He can maximize his chances of making a profit by applying “a marginal analysis”. As such, he will guesstimate the expected rise in profits from hiring one more employee, or putting to work one more unit of capital. Needless to say, he will make the investments only if the expected return is at least equal, but preferably significantly higher than the costs he is sure to incur. And every entrepreneur knows that if he miscalculates, the sanction is that losses will soon appear, followed by bankruptcy.

So, in a normal capitalist system, after a few cycles only the fellows who have a long history of making good decisions survive. And these results are achieved because they all apply some kind of marginal analysis on when to stop investing, or when to increase investments. This is another way of saying that mistakes are constantly made by bad, or unlucky entrepreneurs. As a result, the system in the short term moves between unstable equilibriums, but over the long term achieves a very stable equilibrium. The exception occurs when some exogenous shock, usually generated by the state, hits the system—i.e. wars, protectionism, increased regulation, massive monetary mistakes or tax increases. These are my five cardinal sins of capitalism and they all cause a lower return on capital.

Let us now compare this very simplistic approach to the current doxa—the Keynesian model. In such a shiny modern paradigm, the starting point is quite different as the “enlightened” elites (i.e. the government or central bank) operate by outsmarting the business people.

In the Keynesian model economy, let’s assume that entrepreneurs have decided that investing makes no sense (for whatever reason) as “expected” returns have fallen below baked-in costs. The Keynesian solution is for the government to start spending money to boost final demand since a fall in profitability always stems from a “lack of demand”. If this analysis is correct, then the increase in final demand should, theoretically at least, boost the expected return of all entrepreneurs, stimulating their “animal spirits” back to a normal level. This rise in animal spirits, or willingness to take risk, should then lead to an increase in investment and in hiring, and bingo, the economy, instead of contracting, should start to expand again.

I would make the following three observations:

Firstly, entrepreneurs may chose not to invest for reasons other than the famous lack of demand. If a collapse in capital spending and hiring stems from a new invention such as railways in the 19th century—with the effect that stage coach manufacturers are rendered obsolete—no amount of government spending will help. So the Keynesian model is useless in times of huge technological change. The first thing which will happen is that the country stimulating demand will face a big deterioration in its current account, together with a rapid rise in government debt. The second effect will be to waste that most scarce resource, namely, capital. Stimulating demand may work if there is no progress. But following a Keynesian policy in a time of surging technological change verges on the criminal. As an aside, Keynes believed in the 1930s that no new inventions were coming, so his recommendations were at least internally coherent.

Secondly, Keynesian economists believe they can compute where the economy should be with reference to where it is now, thereby justifying state intervention. They do this by calculating something dubbed the “output gap”. If their sums show there is such a gap (GDP below its potential), then the government should start spending money (again). This method implies that economists can forecast, for example, the productivity growth and the size of the future labor force. Yet as Mervyn King, the former governor of the Bank of England, said when asked to predict the following year’s level of UK GDP: “Next year? If only I knew what it had been last year.” Lord King was simply making the point that nobody can forecast properly, and certainly not a fuzzy concept like GDP. After all, I don’t recall reading warnings of a potential decline in productivity from economists at the Federal Reserve or the International Monetary Fund. Moreover, they have not been able to explain the collapse in the US labor market participation rate. Bottom line: all Keynesian policies assume that economists can forecast the future. I would only note that scientific philosopher Karl Popper found this notion risible as the future is by definition unknowable. In truth, to believe that any social phenomena can be forecast is to move from science to religion—my contention is that Keynesian economics has become such an endeavor.

Thirdly, government intervention is always accompanied by big rises in public debt as a share of GDP since “social goods” like infrastructure and education get prioritized. Such spending is generally couched in terms of “investing in our future” so few people object. However, I would advise a focus on marginal returns. Government spending like anything in life is the victim of diminishing returns. Take infrastructure, where up to a point high returns can be earned from state investment. At first, “shovel ready projects” will generate a positive return, but over time those returns will progressively diminish. Then, at a certain point, “new” investments will have a negative return (bridges to nowhere and too many doctorate students in sociology). At such a point, fresh investment of this nature leads inexorably to an absolute decline in national output. I would venture that identifying the threshold when extra government spending leads to lower GDP should be a key issue for today’s economists. Funnily enough, I have never seen anything published on this touchy topic.

Sweden was probably the first country to enter this new era in the early 1990s, Japan followed at the end of the 1990s while France and Italy crossed the threshold early in the 21st century. The US is probably reaching this point as I write. Hence, if we have reached a juncture when many countries face negative returns on any marginal rise in government spending, then it is simple math that the only way to return to economic growth is to cut government expenditure.

Moreover, there is evidence that such an approach works. Take Sweden in 1992, Canada in 1994 or the UK in 2010. In all cases, once government spending was cut the economy recovered quite smartly—no such situation has been seen in Japan or in France.

To summarize, in a normal “non-Keynesian” economy, activity changes according to the relationship between the marginal cost of capital and labor and their marginal returns. If central banks or governments do not intervene in the process, then the economic cycle will be subdued and operate according to Wicksellian principles. At this point, the economy will grow very close to its optimal level as the US managed during the “great moderation”.

On the other hand, if the government tries to artificially inflate the expected return on capital (by stimulating demand) it will cause a misallocation of capital, before the return on capital slides back toward its pre-stimulus level, or more likely down to a lower level. I have made the same point many times with respect to central bank efforts to manipulate the cost of capital lower through “euthanasia of the rentier” policies. Whatever mode of manipulation is chosen, the results are predictably ghastly in the shape of zombie companies, capital being allocated by central planning and a decline in the economic growth rate.

Keynes famously noted “over the long term we are all dead”. After decades of Keynesian policies, we can begin to make long term judgements. If the world wants to return to a growth period, then perhaps interest rates should be raised and government spending cut massively, now. Should the current low interest rate mantra be maintained and government spending be boosted yet more, then we will likely move from our current stagnation to something much nastier.

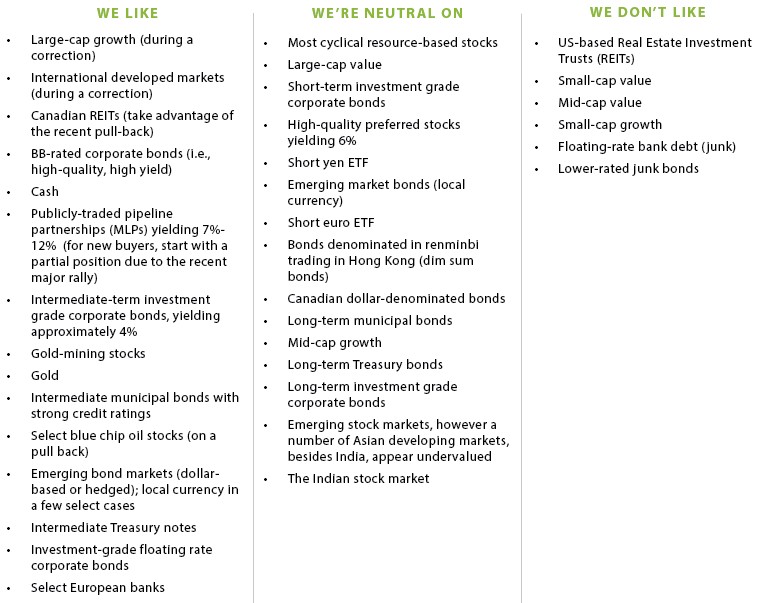

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

No changes this week.

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.