“There are risks and costs to a program of action. But they are far less than the long-range risks and costs of comfortable inaction.”

-JOHN F. KENNEDY, 35th U.S. president

Dimon Vision. After spending almost four decades in the financial industry, I have many fond memories (along with a few of the not-so-fond variety). Among my best are the times when I was privileged to work with Jamie Dimon in the 1990s. These were my—and Jamie’s—Smith Barney years and they were exhilarating.

As with so many once-storied Wall Street firms, the Smith Barney name has been merged into oblivion. But, back then, it was one of the best brokerage firms in America. In 1990, Jamie and his mentor Sandy Weill gave my team the chance to initiate the Portfolio Management (PM) Program at Smith Barney. This was a novel approach in days of yore, allowing a broker to move into the role of de facto investment advisor for her or his clients, charging an asset management fee instead of commissions.

Fortunately, the PM program turned out to be highly successful at Smith Barney. In 1993, "Barney" bought out the old Shearson (another once-storied name that has disappeared into the slip-stream of time). As a result, what had been an equivalent adviser-directed program that harked back all the way to E.F. Hutton (yet another) joined forces with the Smith Barney PM unit. The result was a true money-management juggernaut.

As this expansion occurred, eventually leading to the acquisition of Traveler’s Insurance, then Salomon Brothers and, finally, the blockbuster merger with Citicorp, I had the opportunity to work with Jamie on several integration issues that impacted the PM program. Through this, I developed a deep respect for him that persists to this day. (I even had the chance to meet and play tennis with his parents, who only recently passed away. His dad had been a successful broker and was the consummate gentleman.)

Jamie and I both left Travelers/Smith Barney not long after the 1998 Citigroup deal – in his case involuntarily. As much as I admire Sandy Weill, and am ever grateful for the opportunity he gave me to manage money, I believe his firing of Jamie Dimon was the worst mistake of his career. Without Jamie’s operational brilliance, the extraordinarily complex merger with Citigroup was a ticking time bomb. It eventually exploded in 2008 and what had once been a $56 stock traded below $1. Even today, it remains at a fraction of where it was when Jamie was forced out nearly twenty years ago. It’s safe to say that without TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program), Citigroup would have gone the way of Washington Mutual.

Jamie landed on his feet quickly after his bizarre dismissal from Citi, being named CEO of Bank One in 2000, then the nation’s fifth-largest bank. In a few short years, he turned that troubled institution around and, in 2004, it merged with J.P. Morgan Chase. Jamie was immediately named President and COO of J.P. Morgan Chase, and was made CEO and Chairman of the Board in 2006. Since then, he has become almost synonymous with the mammoth bank he leads (so much so that I sometimes jokingly refer to it as “Jamie Morgan”).

While he had an embarrassing stumble a few years back over the “London Whale” incident—which earned him a Congressional grilling—he deserves immense credit for guiding his institution through the global financial crisis while maintaining a fortress balance sheet. (Though J. P. Morgan received TARP money, it accepted those funds reluctantly.)

Today, J.P. Morgan is riding high and Jamie is a billionaire in his own right. His annual letter to shareholders is always a great read, often with candid admissions of his and his bank’s shortcomings. This year’s edition contained a section that was so cogent and timely I decided to make it into this week’s Guest EVA. (More on that below.)

But first, let me take a brief moment to introduce a young man whose name you have seen in recent EVAs, Michael Johnston, Jr. Hopefully, by now you’ve been impressed with Michael’s skills as a wordsmith. They are especially commendable given that he’s a tender 27 years old. Michael graduated Magna Cum Laude from Seattle Pacific University’s School of Business and Economics. He then worked as a business consultant at Microsoft for 3 years, leading the U.S. Enterprise Marketing department’s communications and business analytics efforts. Despite his not very advanced years, he’s also an avid investor in technology and commodity trading, as well as the author of a children’s book (presumably, not saying that playing the futures markets is child’s play!).

Michael was a great help to me this week in editing down Jamie’s lengthy commentary and summarizing the key points that you will read below. Because of Michael’s summary, I’m only going to make a couple of brief remarks on what my old friend wrote.

First, it’s public information that Jamie is a life-long Democrat. The reason I mention this is that much of what he has written sounds like the polar-opposite of core democratic economic tenets. For example, he notes the explosion in student loan debt since the federal government took de facto control over that marketplace. Actually, the total amount of student indebtedness is now in excess of $1.4 trillion versus $200 billion back in 2010 when the government became “the solution”. Having such a vital part of the population in a condition of virtual indentured servitude is definitely not a good thing for the long-term health of our country.

Second, it shocked me to read that 71% of America’s youth—ages 17 to 24—aren’t eligible for military service due to health and educational deficiencies. What a terribly sad comment this is on how poorly we’ve prepared these young people to make their way in life.

Third, and finally, for those of you who recall our October 21st, 2016 EVA — written in defense of US businesses and in criticism of the overzealous attacks on Corporate America by Elizabeth Warren, et al — Jamie’s section on the inequity of our current tort system is spot-on, in my view. As we noted, and he outlines much more compellingly, US companies are at a huge disadvantage when they try to defend themselves in court, especially when being sued by government entities. It’s almost a guilty-until-proven-innocent type of situation and it’s becoming a massive drag on our economy.

Yet, Jamie’s overall tone and outlook are optimistic. Let’s all hope and pray that eventually our leaders pay heed to some of his eminently rational recommendations, thereby justifying his bullish view of America’s future.

DISCLOSURE: Certain clients of Evergreen GaveKal hold JPMorgan Chase in their accounts, at their discretion; this security has not been recommended by Evergreen. You should not assume that investments in JPMorgan Chase were or will be profitable.

David Hay

Chief Investment Officer

To contact Dave, email:

dhay@evergreengavekal.com

(Note: The following is meant to serve as a summary of this week’s Guest EVA by JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon, which can be found below.)

JP MORGAN CHASE 2016 LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS

By Jamie Dimon

(Note: Jamie’s letter was too long to present in full-form. As such, we have compiled excerpts below. Breaks in writing are noted with ellipses throughout this section. To view the full version of his letter, please click here.)

Before we address some of the critical issues confronting our country, it would be good to count our blessings. Let’s start with a serious assessment of our strengths.

1. The United States of America is truly an exceptional country

America today is probably stronger than ever before. For example:

Very few countries, if any, are as blessed as we are.

2. But it is clear that something is wrong — and it’s holding us back.

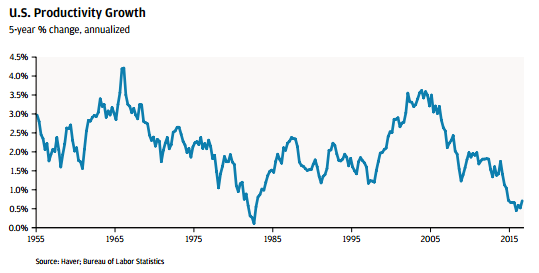

Our economy has been growing much more slowly in the last decade or two than in the 50 years before then. From 1948 to 2000, real per capita GDP grew 2.3%; from 2000 to 2016, it grew 1%. Had it grown at 2.3% instead of 1% in those 17 years, our GDP per capita would be 24%, or more than $12,500 per person higher than it is. U.S. productivity growth tells much the same story, as shown in the chart below.

Our nation’s lower growth has been accompanied by – and may be one of the reasons why – real median household incomes in 2015 were actually 2.5% lower than they were in 1999. In addition, the percentage of middle class households has actually shrunk over time. In 1971, 61% of households were considered middle class, but that percentage was only 50% in 2015. And for those in the bottom 20% of earners – mainly lower skilled workers – the story may be even worse. For this group, real incomes declined by more than 8% between 1999 and 2015. In 1984, 60% of families could afford a modestly priced home. By 2009, that figure fell to about 50%. This drop occurred even though the percentage of U.S. citizens with a high school degree or higher increased from 30% to 50% from 1980 to 2013. Low-skilled labor just doesn’t earn what it used to, which understandably is a source of real frustration for a very meaningful group of people. The income gap between lower skilled and skilled workers has been growing and may be the inevitable consequence of an increasingly sophisticated economy.

…

Many economists believe we are now permanently relegated to slower growth and lower productivity (they say that secular stagnation is the new normal), but I strongly disagree.

…

Many other, often non-economic, factors impact growth and productivity. Following is a list of some non-economic items that must have had a significant impact on America’s growth:

Any one of these non-economic factors is fairly material in damaging America’s effort to achieve healthy growth. Let’s dig a little bit deeper into six additional unsettling issues that have also limited our growth rate.

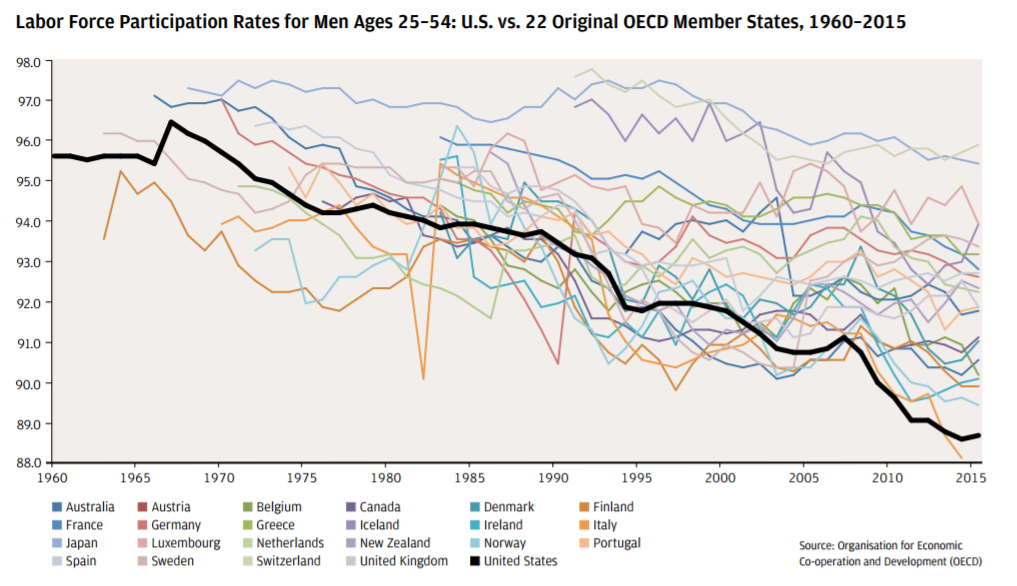

Labor force participation is too low. Labor force participation in the United States has gone from 66% to 63% between 2008 and today. Some of the reasons for this decline are understandable and aren’t too worrisome – for example, an aging population. But if you examine the data more closely and focus just on labor force participation for one key segment; i.e., men ages 25-54, you’ll see that we have a serious problem. The chart below shows that in America, the participation rate for that cohort has gone from 96% in 1968 to a little over 88% today. This is way below labor force participation in almost every other developed nation.

Education is leaving too many behind. Many high schools and vocational schools do not provide the education our students need – the goal should be to graduate and get a decent job. We should be ringing the national alarm bell that inner city schools are failing our children – often minorities and children from lower income households. In many inner-city schools, fewer than 60% of students graduate, and many of those who do graduate are not prepared for employment. We are creating generations of citizens who will never have a chance in this land of dreams and opportunity. Unfortunately, it’s self-perpetuating, and we all pay the price. The subpar academic outcomes of America’s minority and low-income children resulted in yearly GDP losses of trillions of dollars, according to McKinsey & Company.

Infrastructure needs planning and investment. In the early 1960s, America was considered by most to have the best infrastructure (highways, ports, water supply, electrical grid, airports, tunnels, etc.). The World Economic Forum now ranks the United States #27 on its Basic Requirements index, reflecting infrastructure along with other criteria, among 138 countries. On infrastructure, the United States is behind most major developed countries, including the United Kingdom, France and Korea. The American Society of Civil Engineers releases a report every four years examining current infrastructure conditions and needs – the 2017 report card gave us a grade of D+. Another interesting and distressing fact: The United States has not built a major airport in more than 20 years. China, on the other hand, has built 75 new civilian airports in the last 10 years alone.

Our corporate tax system is driving capital and brains overseas. America now has the highest corporate tax rates among developed nations. Most other developed nations have reduced their tax rates substantially over the past 10 years (and this is true whether looking at statutory or effective tax rates). This is causing considerable damage. American corporations are generally better off investing their capital overseas, where they can earn a higher return because of lower taxes. In addition, foreign companies are advantaged when they buy American companies – often they are able to reduce the overall tax rate of the combined company. Because of this, American companies have been making substantial investments in human capital, as well as in plants, facilities, research and development (R&D) and acquisitions overseas. Also, American corporations hold more than $2 trillion in cash abroad to avoid the additional taxes. The only question is how much damage will be done before we fix this. Reducing corporate taxes would incent business investment and job creation.

…

And counterintuitively, reducing corporate taxes would also improve wages. One of the unintended consequences of high corporate taxes is that they actually depress wages in the United States. A 2007 Treasury Department review found that labor “may bear a substantial portion of the burden from the corporate income tax.” A study by Kevin Hassett from the American Enterprise Institute found that each $1 increase in U.S. corporate income tax collections leads to a $2 decrease in wages in the short run and a $4 decrease in aggregate wages in the long run. And analysis of the U.S. corporate income tax by the Congressional Budget Office finds that labor bears more than 70% of the burden of the corporate income tax, with the remaining 30% borne by domestic savers through a reduced return on their savings. We must fix this for the benefit of American competitiveness and all Americans.

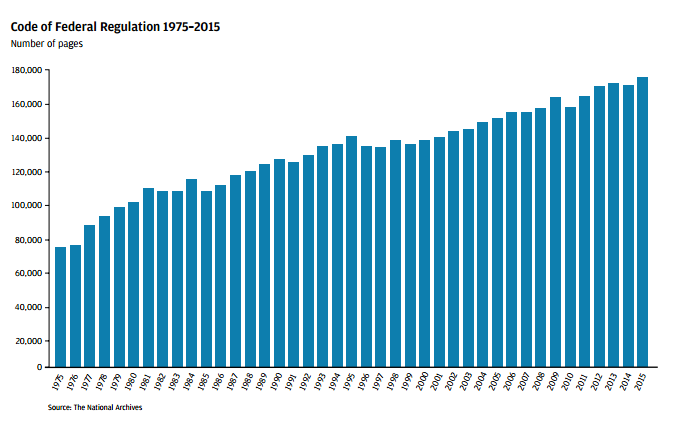

Excessive regulations reduce growth and business formation. Everyone agrees we should have proper regulation – and, of course, good regulations have many positive effects. But anyone in business understands the damaging effects of overcomplicated and inefficient regulations. The chart below shows the total pages of federal regulations, which is a simple way to illustrate additional reporting and compliance requirements.

By some estimates, approximately $2 trillion is spent on regulations annually (which is approximately $15,000 per U.S. household annually). And even if this number is exaggerated, it highlights a disturbing problem. Particularly troubling is that this may be one of the reasons why small business creation has slowed alarmingly in recent years. According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the rising burdens of federal regulations alone may be a main reason for a falling pace in new business formation. In 1980, Americans were creating some 450,000 new companies a year. In 2013, they formed 400,000 new businesses despite a 40% increase in population from 1980 to 2013. Our three-decade slump in company formation fell to its lowest point with the onset of the Great Recession; even with more businesses being established today, America’s startup activity remains below prerecession levels.

While some regulations quite clearly create a common good (e.g., clean air and water), it is clear that excessive regulation does not help productivity, growth of the economy or job creation. And even regulations that once may have made sense may no longer be fit for the purpose. I am not going to outline specific recommendations about non-financial regulatory reform here, other than to say that we should have a permanent and systematic review of the costs and benefits of regulations, including their intended vs. unintended consequences.

…

3. How can we start investing in our people to help them be more productive and share in the opportunities and rewards of our economy?

We need to work together to improve work skills. I cannot in this letter tackle the complex set of issues confronting our inner-city schools, but I do know that if we don’t acknowledge these problems, we will never fix them. Whether they graduate from high school, vocational or training school or go on to college, our students can and should be adequately prepared for good, decent-paying jobs. And whether a student graduates from high school, vocational school or training school, the graduate should have a sense of pride and accomplishment – and meaningful employment opportunities, without forgoing the chance to go to college later on. Career and technical education specifically can give young people the skills they need for decent paying roles in hundreds of fields, including aviation, robotics, medical science, welding, accounting and coding – all jobs that are in demand today. In New York City, not far from where I grew up in Jackson Heights, Queens, there’s a school called Aviation High School. Students travel from all over the city to go to the school (with a 97% student attendance rate), where they are trained in many facets of aviation, from how to maintain an aircraft to the details of the plane’s electronics, hydraulics and electrical systems. And when the students graduate (93% graduated in the normal four years), they get a job, often earning an annual starting salary of approximately $60,000. It’s a great example of what we should be promoting in our educational system.

…

Proper skills training also can be used to continuously re-educate American workers. Many people are afraid that automation is taking away jobs. Let’s be clear. Technology is the best thing that ever happened to mankind, and it is the reason the world is getting progressively better. But we should acknowledge that though technology helps everyone generally, it does cause some job loss, dislocation and disruption in specific areas. Retraining is the best way to help those disrupted by advancements in technology.

…

4. What should our country be doing to invest in its infrastructure? How does the lack of a plan and investment hurt our economy?

Infrastructure in America is a very broad and complex subject. However, we do have a few suggestions on how to make it better.

Similar to companies planning for capacity needs, it is quite clear that cities, states and the federal government can also plan around their somewhat predictable needs for maintenance, new roads and bridges, increasing electrical requirements and other necessities to serve a growing population. Infrastructure should not be a stop-start process but an ongoing endeavor whereby intelligent investments are made continuously. And the plan could also be sped up if necessary to help a weakening economy.

Infrastructure, which could have a life of five to 50 years, should not be expensed as a government debt but should be accounted for as an investment that could be financed separately. Borrowing money for consumption is completely different from borrowing for something that has value for a long period of time. It’s important to streamline the approval process, and approvals should run simultaneously and not sequentially.

Last, we need to assure that we have good infrastructure and not bridges to nowhere. Good infrastructure serving real needs is not only conducive to jobs in the short run but to growth in the long run. Projects should be specifically identified, with budgets and calendars and with responsible parties named.

5. How should the U.S. legal and regulatory systems be reformed to incentivize investment and job creation?

There are many reasons to be proud of our system of government. The U.S. Constitution is the bedrock of the greatest democracy in the world. The checks and balances put in place by the framers are still powerful limits on each branch’s powers. And this year, we witnessed one of the hallmarks of our great nation – the peaceful transition of power following a democratic election.

Our legal system, including our nation’s commitment to the rule of law, has long been a particular source of strength for our economy. When people, communities and companies are confident in the stability and fairness of a country’s legal system, they want to do business in that country and invest there (and come from overseas to do so). Knowing that you will have access to courts for a fair and timely hearing on matters and that there are checks against abuses of power is important. As the discussion about areas for potential reform continues, it is critical that these long-term U.S. advantages are kept in mind and preserved.

In regulation, for example, I worry that the distribution of power has shifted. Congress, through the Administrative Procedures Act (APA), set out how regulators should publish draft rules. The APA allows for comments on draft rules, including comments on how a proposed rule will impact lending, jobs and the economy. Today, however, agencies often regulate through supervisory guidance that isn’t subject to the same commentary or checks. The function of interpretive guidance is to clarify or explain existing law and should not be used to impose new, substantive requirements. Now is a good time to discuss how to reset this balance.

There also is an opportunity to have a similar conversation around enforcement and litigation. On the civil side, we should look closely at whether statutory damages provisions work as intended. I read recently about a settlement under the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act in which plaintiffs received in excess of $30 million from a business that printed credit card receipts with the customer’s card expiration date. Is that fair and proportionate – or is the result driven by a statutory damages framework that should be reconsidered?

And simply because the company agreed to the settlement does not mean it was the right result. Here is the fact: The current dynamics make it very hard for companies to get their day in court – as the consequences of a loss at trial can be disproportionately severe. This is particularly true in a government-initiated case. The collateral consequences of standing up to a regulator or losing at trial can be disproportionately negative when compared with the underlying issue or proposed settlement, and it can lead to the decision not to fight at all, no matter what the merits of the case may be. The Institute for Legal Reform, for the Chamber of Commerce has framed this issue as follows:

“The so-called ‘trial penalty’ has virtually annihilated the constitutional right to a trial. What are the consequences of a system in which the government is only rarely required to prove its case? What are the implications of this on businesses, both large and small? Ultimately, what are the long-term prospects for entrepreneurship in an environment where even the most minor, unintentional misstep may result in criminal investigation, prosecution and loss of liberty?”

When you combine this with the fact that businesses have no “penalty-free” way to challenge a new interpretation of the law, the net-net result is a system that fosters legislation by enforcement actions and settlements. Said differently, rather than Congress expanding a law or a court testing a novel interpretation, regulators and prosecutors make those decisions and companies acquiesce.

The impact of these issues is further exacerbated by a system that allows for “multiple jeopardy,” where federal, state, prudential and foreign agencies can “pile on” to any matter, each seeking its own penalty without any mechanism to ensure that the multiple punishments are proportionate and fair. It would be like getting pulled over by a local police officer and getting fined by your local town, then by your county, then by your state, then by the federal government and then having the U.N. weigh in since the car was made overseas.

To be clear, we need regulators focused on the safety and soundness of all institutions. We need enforcement bodies focused on compliance with the law. But we also need to preserve the system of checks and balances – when you cannot get your day in court on some really important issues, we all suffer.

We need to improve and reform our legal system because it is having a chilling impact on business formation, risk taking and entrepreneurship.

6. What price are we paying for the lack of understanding about business and free enterprise?

The United States needs to ensure that we maintain a healthy and vibrant economy. This is what fuels job creation, raises the standard of living for those who are hurting, and positions us to invest in education, technology and infrastructure in a programmatic and sustainable way to build a better and safer future for our country and its people. America’s military will be the best in the world only as long as we have the best economy in the world.

Business plays a critical role as an engine of economic growth, particularly our largest, globally competitive American businesses. As an example, the thousand largest companies in America (out of approximately 29 million) employ nearly 30 million people in the United States, and almost all of their employees get full medical and retirement benefits and extensive training. In addition, these companies account for more than 30% of the roughly $2.3 trillion spent annually on capital expenditures. Capital expenditures and R&D spending drive productivity and innovation, which ultimately drive job creation across the entire economy.

To support this, we need a pro-growth policy environment from the government that provides a degree of certainty around longstanding issues that have proved frustratingly elusive to solve. The most pressing areas in which government, business and other stakeholders can find common ground should include tax reform, infrastructure investment, education reform, more favorable trade agreements and a sensible immigration policy, among others.

When you read that small businesses and big businesses are pitted against each other or are not good for each other, don’t believe it. Small businesses and large businesses are symbiotic – they are substantial customers of each other, and they help drive each other’s growth – and are integral to our large business ecosystem. At JPMorgan Chase, for example, we support more than 4 million small business clients, 15,000 middle market companies, and approximately 7,000 corporations and investor clients. We also rely on services from nearly 30,000 vendors, many of which are small and midsized companies. Business, taken as a whole, is the source of almost all job creation.

Approximately 150 million people work in the United States; 130 million work in private enterprise. We hold in high regard the 20 million people who work in government – teachers, policemen, firemen and others. But we could not pay for those jobs if the other 130 million were not actively producing the GDP of America. Something has gone awry in the public’s understanding of business and free enterprise. Whether it is the current environment or the deficiency of education in general, the lack of understanding around free enterprise is astounding. When businesses or individuals in business do something wrong (problems that all institutions have, including schools, churches, governments, small businesses, etc.), they should be appropriately punished – but not demonized. We need trust and confidence in our institutions – confidence is the “secret sauce” that, without spending any money, helps the economy grow. A strong and vibrant private sector (including big companies) is good for the average American. Entrepreneurship and free enterprise, with strong ethics and high standards, are worth rooting for, not attacking.

7. Strong collaboration is needed between business and government.

We all can agree that a general dissatisfaction with the lack of true collaboration and willingness to address our most pressing policy issues has contributed to the existing divisive and polarized environment. Certainly there is plenty of blame to go around on this front. However, rather than looking back, it is now more important than ever for the business community and government to come together and collaborate to find meaningful solutions and develop thoughtful policies that create economic growth and opportunity for all. This cannot be done by government alone or by business alone. We all must work together in ways that put aside our “business-as-usual” approaches. The lack of economic opportunity is a moral and economic crisis that affects everyone. There are too many people who are not getting a fair chance to get ahead and move up the economic ladder. This runs contrary to the fundamental idea that America is a country where everyone has an opportunity to improve their lives and that future generations of Americans know they can be just as successful as those who came before them.

By working together and applying some good old American can-do ingenuity, there is nothing that we can’t accomplish. By working together, the business community, government and the nonprofit sector can ensure and maintain a healthy and vibrant economy today and into the future, creating jobs, fostering economic mobility and maintaining sustainable economic growth. Ultimately, this translates to an improved quality of life and greater financial security for those who are struggling to make ends meet. It also would be a significant step in restoring public faith in two of our greatest democratic institutions – U.S. business and government – and would allow us to move forward toward a prosperous future for all Americans.

OUR CURRENT LIKES AND DISLIKES

Changes in bold.

LIKE

NEUTRAL

DISLIKE

DISCLOSURE: This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Any opinions, recommendations, and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions, reflect our judgment as of the date of this presentation, and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed and Evergreen makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness.